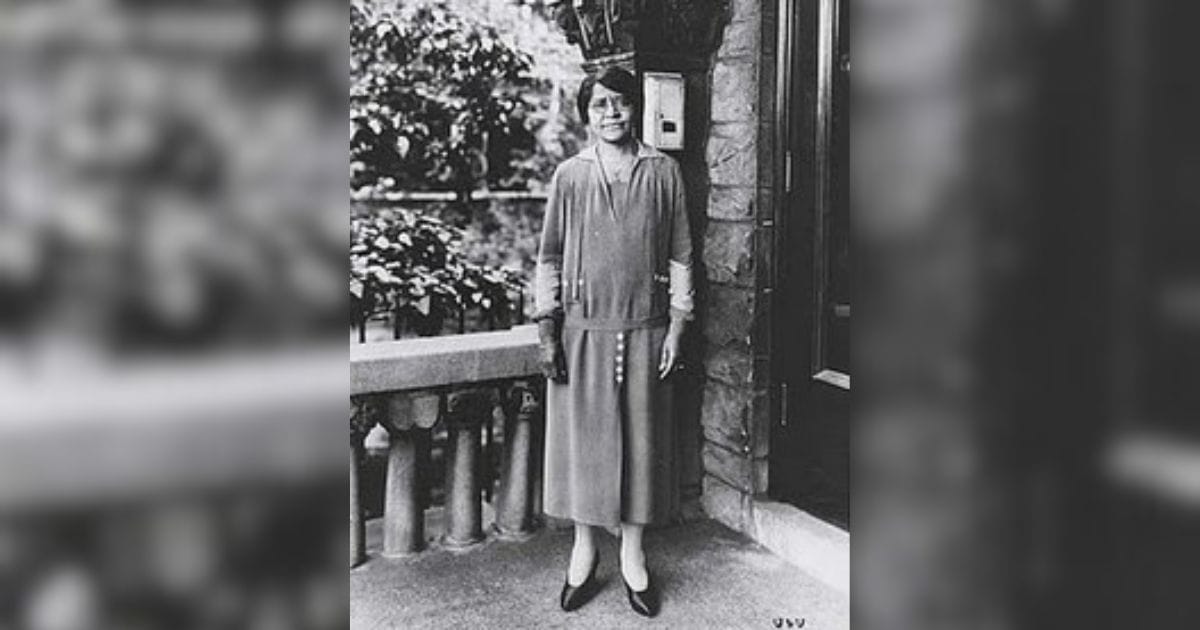

Annie Turnbo Malone

The Millionairess

By the time she died at Chicago’s Provident Hospital in 1957 from a stroke, 87-year-old Annie Turnbo Malone was nearly broke, a former business titan, twice scorned, who was slowly becoming a fading memory. The millionaire philanthropist joins numerous Black women of her time – some famous, others infamous – who represent the ancient landmarks; each now covered in dust kicked about by the heels of Black America’s traveling shoes.

These powerful women, along with the men who preceded, accompanied or followed them, carved their places in history. Like Turnbo, they thrived despite the Black Codes, Jim Crow, legalized segregation, and systemic poverty, while also facing crazed, white lynch mobs that could spring up at any time. According to the NAACP, between 1882 and 1968, more than 4,743 documented lynchings occurred in the U.S.

In 1860, the Black population in the U.S. stood at roughly 4.5 million (16.5%) people, most of whom were enslaved. The Reconstruction period began in 1865 until 1877, following the Civil War which freed most of the enslaved Blacks, and was the starting process of readmitting 11 states back into the Union. White plantation owners and benefactors of slavery received federal restitution, while the people of African descent most impacted by the system, received federal assistance, but no money or land. For many emancipated people, the North became the new “promised land” and millions embarked on a trek to shepherd new lives, to find opportunity.

Annie Minerva Turnbo was born to formerly enslaved people on August 9, 1869 in Metropolis, Illinois. The city is located along the Ohio River near the state’s southern border, about nine miles from Paducah, Kentucky. Orphaned at a young age, she moved to Peoria, Illinois to live with her older sister. As a child, she developed a keen interest in chemistry and hair and as a teenager began creating her own hair-care products.

Turnbo developed a line of non-damaging hair straighteners, oils, hair-growing stimulants and other products specifically for African American women. Soon after its commercial release in 1902, her “Wonderful Hair Grower” transformed hair-methods for its consumers, and was the start of her growing empire. Sold door-to-door by a mostly Black female salesforce, the product’s pitch included the offer of “free treatments” to potential customers.

Before opening her first salon, Turnbo made a name for herself as a teacher of entrepreneurs. Her biographers note that she encouraged her sales team to become students of the craft, and began teaching them her methods. Among them was a young Sarah Breedlove Davis, who later would be accused by Turnbo supporters of stealing her mentor’s formulas and rebranding them under the brand, “Madame C. J. Walker.”

Not deterred by imitators, Turbo copyrighted her method in 1906 as the “Poro Method,” so named for a West African concept of disciplining and enhancing the body both spiritually and physically. Four years later, she extended her distribution network nationally. She frequently trademarked all of her products.*

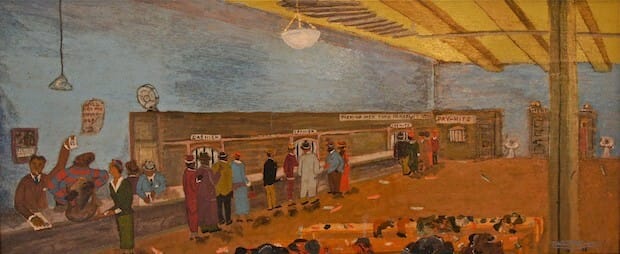

Turnbo’s customers included scores of women who flocked to beauty salons bearing her name. They, along with high-profile African American women in church, education and society, became her biggest cheerleaders. They responded positively to her product launches with their dollars. The business woman enhanced her word-of-mouth marketing by placing large display ads in Black-owned newspapers. The revenue generated from sales of her Poro products led Turnbo to open Poro Beauty College in 1918.

Movers and shakers from throughout Black America attended its grand opening.

The four-story cosmetology school trained hundreds of beauticians in the proper application of her “Poro System” of cosmetics, hair care and overall wellness for African American women. It was a massive complex. According to “Unwavering Annie Malone,” by Dr. Leslie Best, “The Poro College new building was designed and built by Albert B. Groves a distinguished architect in St. Louis… It was a three-story building that covered an entire block that included a mezzanine, basement, and a rooftop garden. Inside there was the Poro College manufacturing department, general offices, beauty culture facility with 31 booths for shampooing, massaging, manicuring and class instructions. There was an auditorium that seated 800 persons,, dining room, kitchen, and dormitory rooms for students.

“Also, the property, which also houses the Malones, offered an ice cream parlor, bakery and medical office spaces to serve the public. The cost of the construction was $250,000,” Dr. Best noted.

Women for nearby cities and neighboring states traveled to St. Louis to enroll. For them Poro was not just about learning about the emerging haircare trade, but was also a way to earn independence, financial stability and racial pride. If they did not go into business after graduation, they could seek competing wages at Black-owned hair salons throughout the country that touted Turnbo’s methods.

The businesswoman was soon among the biggest philanthropists for Black causes. Malone’s charitable giving included orphanages, churches, missions, food kitchens, organizations working to soothe racial tensions or assist illiterate and impoverished African Americans. She was a member of the National Negro Business League, established in 1900 by Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute.

In 1903, 34-year-old Annie married Nelson Pope. The marriage ended soon after the millionairess realized her spouse had married her for the wrong reasons. She accused him of trying to take control of her business venture and exploit her finances for his own gain and they divorced. In 1914, at age 45, she married Aaron Malone, a teacher and part-time salesman, and soon thereafter he was named president and chief manager of her businesses.

According to Turnbo Malone’s official bio and other sources, by 1926, Poro College employed 175 people. Franchised outlets in North and South America, Africa, and the Philippines, employed some 75,000 women. “It is believed that she was worth $14 million at one point during the 1920s. Her 1924 income tax totaled nearly $40,000. However, despite her wealth, Malone lived conservatively and gave away much of her fortune to help other African Americans,” according to historians.

For a while the power couple thrived in St. Louis, growing both of their names in local social circles and among the Black elite throughout the country. But less than six years into their marriage, the Malones became embroiled in a quest for power that became fodder for Black gossip columnists. In 1927, it got real when Aaron Malone filed for divorce and demanded half his wife’s multi-million dollar business. He argued that Annie’s success was due to contacts he’d brought to the Poro company.

According to historians, to aid his cause, Mr. Malone obtained the help of Black leaders, preachers and elected officials who sided with him in the highly publicized divorce. Turnbo drew the support of prominent Black female leaders, including Mary McLeod Bethune, president of the National Association of Colored Women. The divorce settlement, in addition to real estate and other items, also included a payment of $200,000, to her husband, which today is the equivalent of $3.5 million.

An unintended consequence of the divorce, was the revelation and insight into her abundance and personal wealth. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) accused Turnbo Malone of a significant amount of back taxes on real estate and luxury items; and began years of repeated harassment. He was forced to sell the St. Louis property. Malone’s business was further crippled by enormous debt to the government.

After finding success, love and loss in St. Louis, Turnbo Malone, perhaps spurred by the public embarrassment of a nasty, divorce felt it was time to seek new horizons. She told the St. Louis Dispatch, on August 3,1930 “I had to spend too much time on the road between St. Louis and Chicago so I decided to concentrate in the place where the business was larger.”

The entrepreneur headed to the grimy and glistening Windy City and moved to Bronzeville, the “Black Metropolis” and “Black Business Mecca” to spread her wings, restore her dignity and increase her pockets.

THE GRIFTERS

At the turn of the century, Chicago had evolved into a bustling megacity, transforming itself from a wilderness outpost and military fort. In 1833, the city was a small settlement with 850 residents. By 1900, pioneering city planners and engineers built a canal and sewer system, elevated streets to combat flooding, reversed the Chicago River to prevent sewage and water contamination, established lucrative railroad and transportation systems, built slaughterhouses and skyscrapers to help stabilize the homeland of now 1.7 million people.

Chicago also became well known during its growth spurt for its intertwining history of organized crime. Named for a stinking weed “checagou” that smelled like a cross between a rotting onion and mold, the city’s population was just over 80,000 people. Between 1920 to 1940s, the city’s “Black Belt,” a cluster of South Side neighborhoods, was a hub for culture, business and community. It was also the target for economic exploitation by financial predators, and unchecked and often unprosecuted racial violence by their white neighbors.

In the city’s early formation, it had no formal police force. The town that would one day become the nation’s third largest city, was ripe back then for exploitation. White men such as Michael Cassius Donald arrived in Chicago in 1868 and became one of the city’s early crime bosses. In addition to numerous illicit activities, he was known as the “gambling kingpin” and was considered the “mayor of the unofficial city hall,” research shows. The most famous gangster of the 20th Century arrived in Chicago in 1919 after giving it a go in New York. His relationships with the 5th floor gave him political protection as he expanded his bootlegging, prostitution, narcotics trafficking and murder, while living on the city’s South Side.

Though Irish, Italian and other ethnic white figures in Chicago’s underworld are the most celebrated and researched, little can be found about seven Black women who were so prolific in their crimes in the city early days, they were deemed ‘extraordinary” as the most left law enforcement dumbfounded.

By the time Turnbo moved to Chicago for fortune and fame, a notorious group of Black female collaborators took a different path toward infamy. Flossie Moore, Ella Sherwood, Hattie Washington, Mary White, Emma Ford, Pearl Smith and Laura Johnson were known as one of the city’s “extraordinary gang of criminals to ever operate” at the time. According to “Gem of the Prairie: An Informal History of the Chicago Underworld,” by Herbert Asbury, working the pairs, the group committed hundreds of arm robberies, before they were eventually caught and sent to prison throughout the late 1890s and into the 20th Century.

According to “Gem,” White, known as the “Strangler,” was said to have stolen $50,000 in three years. That is $1.7 million in today’s currency value. She, along with her sisters in crime, were said to have used razors, brass knuckles, handguns, sawed-off baseball bats and other tools to exact their crimes. One of the women was described by an arresting officer as remarkable-looking.

“Slightly over six feet tall, weighing two hundred pounds, arms so long that she could scratch her knee-caps without stopping, an almost masculine physique, and tremendous strength combined with catlike agility,” said Detective Clifton R. Wooldridge of Emma Ford. “She would never submit to an arrest except at the point of a revolver.”

Woodbridge chronicled the exploits of many criminals in a number of books including, “The Devil and The Grafter and How They Work Together to Deceive, Swindle and Destroy Mankind.”

He said Ford exuded so much power, “no two men on the police force were strong enough to handle her, and she was dreaded by all of them,” Woodbridge recalled. “…(in Cook County Jail) she nearly drowned a guard by holding him submerged in a water-trough; in the House of Correction she went on a rampage in the laundry and disfigured 12 female convicts; and, she held a prison guard off the floor by his hair while she plucked out his whiskers and threw them in his face.” He also accused Ford and another woman of killing a man in Denver.

From March 1898 to April 1907, Det. Woodbridge served in the office of the General Superintendent of Police in Chicago. Over the course of his career he arrested 19,500 people, sent 3,200 of them to the penitentiary or adjacent institutions and allegedly rescued 100 under age girls from that era’s form of sex trafficking. It should also be noted that the award-winning detective also received 1,200 complaints which at times referred him to investigation and disciplinary action.

The seven grifters operated out of a Near West Side tenement located at No. 202 Custom House Place. The residential property was owned by another Black woman of alleged ill-repute. Lizzie Davenport, was accused of intentionally murdering another Black woman named Sadie Kirk on January 3, 1890. As landlord and occasional collaborator, she allowed her sister gangsters to use the panel house, which doubled as a sort of hotel, to rob unsuspecting patrons. She became something of a master thief and queenpin.

Over a ten-year period authorities claimed, Davenport liberated $500,000 ($18 million today) from unsuspecting borders. She also had other alleged vices and criminal pursuits, all operated under the cover of her modest real estate holdings. The building where the all-female gang held out today, is known as 610 S. Canal Street, where the headquarters of the local office of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

In 1925, the average salary in the United States stood at about $1,236 per year, with a modest home fetching about $5,000. Most African Americas, many resorting to menial labor, earned pennies on the dollar. In Chicago, and other northern cities, a majority of Black residents lived below the poverty line. To make ends meet, many people resorted to underground economics, including bootlegging, numbers-running, and gambling. In 1885, a white guy named Patsy King, an Asian guy called King Foo, and “Policy” Sam Young, a suave Black gangster, supposedly introduced “Policy” to Chicago. Playing policy requires a person to place a bet by attempting to guess three numbers from 1 to 78 drawn from a tumbling drum or other methods.

By 1938, an estimated $18 million annually was bet on Chicago’s policy wheels—with most of those dollars circulating in the city’s Black neighborhoods. With 4,200 policy stations on the South Side alone, some 100,000 reportedly played the numbers each day with pennies, nickels, quarters and a dollar or two. In 1974, the game was legalized years after the program was strong-armed by white gangs, mobsters and elected officials. Elected to the Illinois House in 1964, Harold Washington, who established the state’s holiday honoring Martin Luther King, Jr., led efforts to redirect lottery proceeds to underserved communities after it was taken over by the state.

But more than three decades before Washington emerged, leaders in Chicago’s Black underground scene stabilized people’s homes, churches and businesses, by donating to social caucuses, providing scholarships to needy students, and assisting homeowners with mortgage payments and car notes. Though, little is recorded to indicated the seven Negro women who ruled the Black Belt were either philanthropic or concerned about their brethren’s social plight.

The most detailed accounting of the gang’s efforts, offered by Asbury, involved Ella Sherwood. Having given a friendly tavern owner $375 ($9,129 today) to hide while she laid low, when Sherwood returned to retrieve the loot the bartender refused to return it. The woman then proceeded to break all of the bar’s windows with a bat, emptied the cylinders of two guns she carried into the walls, mirrors and liquor bottles behind the man, before (one might presume) getting for what she had come.

Other members of the gang were known to be prolific at pickpocketing, various con gangs and hustling as well as committing strong armed robberies.

The most dangerous of the seven women were sisters, the aforementioned Ford, and Flossie Moore. Woodbridge recalled that both siblings were as adept at intimidation as they were at committing petty crimes. In “Gem on the Prairie,” the detective described Moore as, “the most notorious female bandit and footpad that ever operated in Chicago.”

Between 1889 to 1893, Moore was active in Chicago’s vice districts and stored more than $125,000 ($4.2 million in today’s currency). According to Abury, the woman once said, “…a holdup woman who couldn’t make more than $20,000 a year in Chicago should be ashamed of herself.”

The author goes on to state, “She always carried a big roll of bills in the bosom of dress and another in her stocking. She kept a… lawyer on her payroll at $125 a month, appeared at balls given by Negro prostitutes and brothel-keepers in gowns that cost five hundred dollars each. And gave her lover, a white man named Handsome Harry Gry, an allowance of $25 per day.”

After bouts in jail or Joliet prison that often put her in solitary confinement, Moore is suspected to have left the city for New York sometime after 1900. Though these women prospered from their illegal and dangerous activities, little is known what happened in their later lives.

TURNBO’S LAST YEARS

The first Great Black Migration was nearing its end by the time, 61-year-old Turnbo Malone relocated to Chicago in 1930. As a emerging “Black Metropolis,” the city full of new migrants from the South. Both the South and West sides were African American migrants lived, has developed a unique cultural aesthetic created by a mix of music, art, and regional southern heritage. The popularity of her Poro products, made Turnbo Malone a welcomed and prominent figure in Chicago’s Black Belt. Thousands of Black women flocked to purchase her products and frequent her local salons. She moved and operated her companies out of Bronzeville.

Though she found welcomed arms in Chicago, Turnbo Malone still faced a campaign by the IRS that would lead to numerous fines, liens on her St. Louis properties and other financial trouble. In 1937, a lawsuit brought by an ex-employee who alleged they were not compensated for their contribution to a Poro product, she was forced to sell the St. Louis Poro property.

Undeterred, Turnbo Malone reopened Poro Beauty College (address). At its height the school housed boarding rooms, a classroom, a restaurant, science labs, and a manufacturing division. She also continued to open salons, and licensed the “Poro Method ” to professional cosmetologists throughout the country. The school encompassed an entire city block. And, her home was among the most expensive owned by Black Americans during her period.

Turnbo Malone continued her philanthropic efforts throughout the U.S., by supporting causes for racial justice and HBCUs such as Tuskegee Institute. As her wealth steadied, the IRS escalated its financial investigations against her businesses. In 1943, she owed almost $100,000 ($1.7 million, today) and news of her financial troubles spread in Black newspapers. Historians note that state and federal governments “were constantly taking her to court and by 1951, it seized control of Poro.”

As her stature diminished and her students began to develop their own successful brands, Turnbo Malone continued to mentor cosmologists and entrepreneurs in Chicago. She remained connected to the numerous charities she helped found in St. Louis, and she at times frequented the church circuit to give an occasional “Women’s Day” speech to congregants.

As World War II raged between 1939 and 1945, Turnbo Malone helped stabilize Black families who continued to sell her popular products door-to-door to supplement their incomes, but also provided support for returning Black veterans.

A “Lincoln Republican,” Turnbo Malone took special interests in the cause of children and impoverished youth. She funded the start of schools, training programs, and provided scholarships for underprivileged teenagers. In 1946, a local orphanage was renamed the Annie Malone Children’s Home in 1946 due to her engagement, leadership and donations. An honorary member of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Turnbo Malone also worshiped as a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Even at an advanced age, Turnbo Malone was a formidable business force. She owned the largest Black hair care distribution plant in the country. Her “Poro Clubs” operated well before Avon Products took hold in Black communities in the 1970s and ‘80s, replacing Black-owned cosmetic products.

On May 10, 1957 Annie Turnbo Pope Malone suffered a stroke and died in the historic Provident Hospital. With no spouse or children she left a tax-burdened estate of roughly $100,000, leaving most of it to a handful of nieces and nephews. Eulogized by Rev. Raymand Ward, her funeral service was held at Bethel AME Church, 4440 S. Michigan Avenue. She is buried in Burr Oak Cemetery.

Dr. Best, “Poro College and Pro Clubs continued to operate until 1989, with the final closing of the Cincinnati Ohio branch. Annie Malone’s home in Chicago Bronzeville is now the location of Mollison Elementary School, 4415 S. King Drive.

This report was made possible by the Inland Foundation and the Crusader Newspaper Group.

-

Stephanie Gadlinhttps://chicagocrusader.com/author/stephanie-gadlin/

-

Stephanie Gadlinhttps://chicagocrusader.com/author/stephanie-gadlin/

-

Stephanie Gadlinhttps://chicagocrusader.com/author/stephanie-gadlin/

-

Stephanie Gadlinhttps://chicagocrusader.com/author/stephanie-gadlin/