INVESTIGATIVE REPORT

The Crusader Takes A CLOSER LOOK

Part III of a IV Part Series

Consumer Protection & Dialysis

To many people on dialysis, Arlene Mullin is nothing short of a saint. For the past two decades she has been a leading voice on Capitol Hill and before state legislatures, in an effort to expose the corruption in the dialysis industry and advocate for patients trying to navigate the complex spider web of health care bureaucracy.

The dialysis hustle is real.

Unbeknownst to most patients, hospital administrators, social work- ers and physicians can refer patients to dialysis centers, products and services without disclosing they are being paid or rewarded for doing so. Mullin, and two federal lawsuits filed in recent years, allege these companies are in violation of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS). Such practices, Mullin and others assert, have cost people their lives.

African Americans suffer from kidney failure at a rate three times higher than Caucasians and constitute more than 35 percent of all patients in the U.S. receiving dialysis for kidney failure. Instead of investing in preventive care treatment, which is shown to lower health care costs, it seems as if the medical system simply waits for Black people’s kidneys to fail in order to put them on dialysis.

“These people need to go to jail, go to jail. They really do,” Mullin told the Crusader. “This is nothing short of attempted murder and murder, period. And, the government has known about it for 23 years.”

Mullin, a former dialysis technician turned whistleblower, began a national campaign to expose corruption in the industry and to better educate dialysis patients. The California native was angry to learn that for-profit dialysis was the only group of medical providers immune to the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law, allowing physicians, and investors like billionaire Warren Buffet, to profit from a dialysis patient’s care.

Buffet, president of Berkshire Hathaway, has invested in DaVita Kidney Care (DKC) since 2011. According to the SEC filing in 2019, the billionaire owns a 29.7 percent stake in the company. He also has stakes in health care insurance companies.

Fresenius and DaVita control the global and U.S. market in dialysis care. Both companies have received slaps on the wrists by the government officials who have given them non-prosecution that resulted in payment of millions of dollars in fines and a promise by executives to self-report any wrongdoing.

“I’ve been doing this going on 23 years and they [dialysis companies] hate my guts,” Mullin said. “Nobody believes this [sort of thing] is happening. And, you know, and it is really funny because the minorities get it. The Caucasians don’t because we have never experienced it. The more profits these companies make the less quality care people receive.”

“Patients really started paying the price,” Mullin explained.

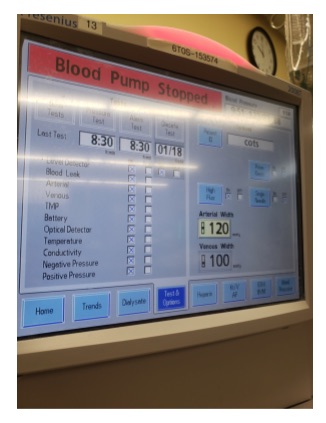

Invented in 1943 by Dutch physician Willem Kolff, dialysis is a process where excess water and toxins are removed from the blood in people whose kidneys cannot perform that function naturally. A four-hour treatment, provided three days per week, can be temporary or last until a person receives a kidney transplant or dies. Once a patient is “on dialysis,” they are mandated to the care of the facility’s medical director, by whom they may have never met or been examined.

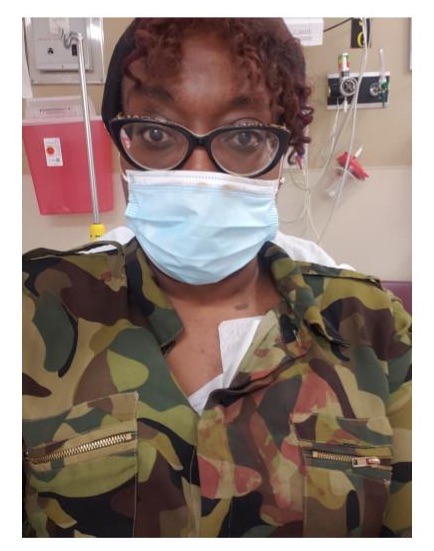

In this reporter’s case, I was diagnosed with end stage renal disease after being taken to the emergency room after passing out while at home from COVID-related pneumonia. Told that I needed “emergency dialysis,” I was whisked to an operating room where a catheter was implanted in my chest, with little explanation.

For several weeks I received dialysis treatments at a Fresenius clinic in South Shore, until the catheter exploded, causing me to be transported to the emergency room again. I was covered in blood, thankful, I suppose, that the shawl I wore over my clothing soaked up most of the blood as it streamed from my wound.

However, suspicious that something was amiss after being told that I’d simply have another device installed and it was no big deal, I self-transferred to Northwestern Memorial Hospital, where a team there determined I did not need dialysis at all.

The people at Northwestern saved my life not from kidney disease, but from what I feel was extreme neglect. They said like many COVID-19 patients, I had suffered an Acute Kidney Injury, and that over time my kidney function would recover. It has, and as of this writing I no longer require dialysis.

This irony of my good news was not lost on me. Had the device not dislodged in my chest, I would have never known I had functioning kidneys.

Like many people, I simply trust what doctors say. I can tell you it was a frightening experience that opened my eyes but also sparked a series of questions for which there were few answers [Visit www.chi- cagocrusader.com to read the first two installments of this series].

The Physician Self-Referral Law, often referred to as the Stark Law, prohibits a physician of Medicare or Medicaid patients from directing people receiving medical treatment to designated health services and providers if the physician has a financial relationship with that entity.

Both federal health programs typically service the elderly, the young, the working poor and indigent citizens. Kidney treatments and transplants are fully covered by the federal government, and remain as the nation’s only demonstration of what “universal health care” looks like.

However, attempting to understand the local, state and federal regulations that govern dialysis companies in Chicago is like a one-armed man trying to put pantyhose on an octopus. It can be done, but you’ve got to pay attention.

HOW TO PLAY MONOPOLY

There are an estimated 7,500 clinics providing kidney dialysis services in the United States. The average annual receipts per clinic are $3.3 million and have an 18 percent net profit margin, according to data reviewed by the Crusader.

For executives of the multi-billion-dollar dialysis companies this is a high stakes game of monopoly—except nobody goes straight to jail.

The Illinois Department of Public Health notes that there are 347 dialysis centers in the state with 157 in Cook County and 78 operating in the boundaries of Chicago.

A FOIA revealed that of those in the city, 79 percent are dominated by Fresenius (34) and DaVita (28). Statewide, these two companies con- trol 82 percent of the Illinois dialysis market.

And neither of them are Black-owned, though most of their clients are African American.

DaVita Kidney Care (DKC) operates 2,539 outpatient dialysis centers in the U.S. and also runs 241 outpatient dialysis centers in 10 other countries. It should be noted that DaVita administers dialysis to patients using products manufactured by Fresenius Medical Care.

Medicare spends more than $114 billion on kidney care per year, according to the most recent government figures, with nearly $80 billion to cover people with chronic kidney disease and another $35 billion spent on end-stage renal disease.

You would think that with such a large investment in kidney care that the U.S. would be the premiere place for kidney care. It isn’t. Renal failure is the 9th leading cause of death in the United States.

A recent whistleblower lawsuit filed claimed Fresenius entered into unlawful arrangements to secure dialysis patient referrals to its outpatient clinics. Specifically, the allegations claimed the company used its dialysis management contracts with hospitals as “loss leaders,” which is a pricing strategy where a product is sold below its market cost to stimulate other sales of more profitable goods or services.

The lawsuit also alleges the company had “a culture of doing whatever it takes” to enter these hospital contracts to induce patient referrals to outpatient centers.

In 2019, the Trump administration issued an executive order to incentivize at-home kidney dialysis and cut the cost of Medicare and Medicaid payments for procedures provided at commercial, standalone clinics.

“Too many Americans don’t shift to more convenient dialysis options, and too many Americans never get a chance at a kidney transplant,” Health and Human Services De- puty Secretary Eric Hargan said. “We believe patients with kidney failure deserve more options for treatment, from both today’s technologies and those of the future.”

So then, why is this happening, and what are lawmakers doing about it? In Illinois there are three laws designed to protect patients and health care consumers from unscrupulous practices.

Under the Illinois Insurance Claims Fraud Prevention Act, it is unlawful to knowingly offer or pay any remuneration, directly or indirectly, in cash or in kind, to induce any person to procure clients or patients to obtain services or benefits under a contract of insurance or that will be the basis for a claim against an insured person or the person’s insurer.

Under the Illinois Consumer Fraud and Deceptive Business Practices Act, “unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices—including but not limited to the use or employment of any deception, fraud, false pretense, false promise, misrepresentation or the concealment, suppression or omission of any material fact, with intent that others rely upon the concealment, suppression or omission of such material fact … in the conduct of any trade or commerce—are unlawful whether any person has in fact been misled, deceived or damaged thereby.”

Lastly, the Illinois False Claims Act, formerly a whistleblower law, provides civil relief for those who report “any person who knowingly presents, or causes to be presented to an officer or employee of the State … a false or fraudulent claim for payment or approval; or knowingly makes, uses or causes to be made or used, a false record or statement to get a false or fraudulent claim paid or approved by the State, or conspires to defraud the State by getting a false or fraudulent claim allowed or paid….”

The Crusader reached out to the office of Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul through phone calls and email and did not receive a response to our request for an interview.

However, in 2009, the office, under Attorney General Lisa Madigan, sued companies accused of referring patients to obtain diagnostic imaging services from 14 Open Advanc- ed MRI centers, without disclosing the doctor’s financial interest. MRI is an acronym for magnetic resonance imaging.

The Complaint alleged that the centers “actively marketed and recruited physicians to enter into… agreements enticing them to be a part of the scheme by offering them as a kickback” for referrals, a substantial portion of the fees charged for certain imaging procedures. Madigan further alleged that the Illinois Insurance Fraud statute was also violated as a result of submitting claims that “falsely identified the referring physician as the person providing the diagnostic services, or falsely indicated the location where the services were performed, or falsely indicated that the referring physician was entitled to bill for those services.”

Even with Illinois case law, the public still remains in the relative dark about how Illinois handles consumer complaints against health care providers and services.

IT’S JUST POLITICS

The federal government spends more than $100 billion per year on health care payments to companies providing dialysis services to patients.

Federal contributions by donors from the top three dialysis companies, between 2008 and 2020, yielded elected officials and candidates for public office nearly $14 million in donations. This money does not include expenditures by political action committees or lobbyists employed to coerce legislators. The amounts also do not reflect the tentacles of the various subsidiaries owned by these global brands or advocacy front groups, which are searchable at [https://tinyurl.com/- fzwr 8c6z].

During the 2020 election cycle alone, DaVita spent $2,149,272, Fresenius spent $1,437,369 and U.S. Renal Care, the third largest dialysis provider in the country, spent the least with $141,974 in donations.

Locally, the names of industry lobbyists are searchable through a public database provided by the Illinois Secretary of State.

As of March, Kasper & Nottage, P.C. Madiar Government Relations, LLC, Roosevelt Group Scarabaeus, LLC were listed as registered lobbyists, under the direction of corporate executive Wendy Scrag, for Fresenius. DaVita shows an equally impressive list of experts skilled in swaying lawmakers to look the other way.

With so much confusion, bureaucracy, money and power in the U.S. dialysis industry, how can anyone be expected to successfully advocate against corporations that are allowed to police themselves? And, where is the oversight?

“When people complain a lot of times it just goes right back to the company,” Mullin explained. “These companies then engage in a scheme to ‘terminate’ treatment for people they deem violent or difficult to work with.

“That means the only time a patient who has been blacklisted by these companies can get dialysis treatment is when they show up in a hospital emergency room,” Mullin said. “By then it is too late. Many of them die.

“Dialysis patients used to live for up to 20 years, and now, the typical life expectancy is three years.

This is because dialysis patients are getting cheaper care, resulting in more profit for the investors,” she said. “But there’s a way to fight back, and we have to, because lives depend on it.”

FINAL INSTALLMENT: The Dialysis Hustle: Tips for Advocacy

Researcher Nairobi Henson and reporter Shayla Simmons contributed to this report, which in part was made possible by The Field Foundation of Illinois, Inc. and the support of Muck Rock, an investigative journalism resource.