Indiana is set to receive millions of dollars from the National Opioid Settlement — but how will it spend those monies? (Darwin Brandis/Canva)

Almost a year after distributions started from the National Opioid Settlement, only $7.1 million has been put to use so far in Indiana as local units of government wrestle with how to make the most of the payments.

Over the next two decades, tens of billions of dollars will flow into state coffers nationally from the National Opioid Settlement, a court agreement between companies deemed responsible for the deadly, life-disrupting impact of the addictive drug and the localities bearing the brunt of the devastation.

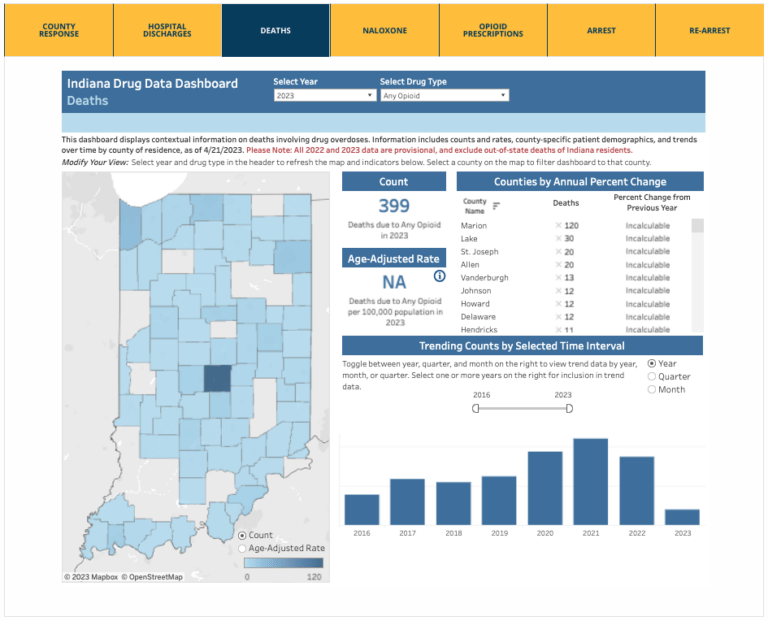

On average, four Hoosiers die each day from a drug overdose and three-quarters of those deaths involved an opioid, according to a 2021 updated drug overdose report from the Indiana Department of Health. More than 15,000 Hoosiers have died since 1999 and thousands more have been incarcerated for drug-related offenses due to their addiction. As with mental health services, jails remain one of the few places to receive treatment in a state with a shortage of options.

But the $507 million coming to Indiana over the next 18 years — from the National Opioid Settlement with distributors AmericsourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson as well as opioid manufacturer Johnson & Johnson — has the potential to change that.

In contrast to its predecessor, the 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement, funds are flowing to local units of government — a move meant to target areas with high numbers of overdose deaths and opioid proliferation.

Payments started going out in December of 2022, with more than $107 million in the first wave to the state and 648 local units of government.

A Fall 2023 report presents the first look at where funds have gone and how localities chose to spend them, falling into a handful of approved uses for funds that include: treatment, prevention and catch-all strategies designed to strengthen local responses.

But, so far, many are being cautious with the money they’ve received or spending their dollars on long-term projects that haven’t yet come to fruition.

Where is the money going locally?

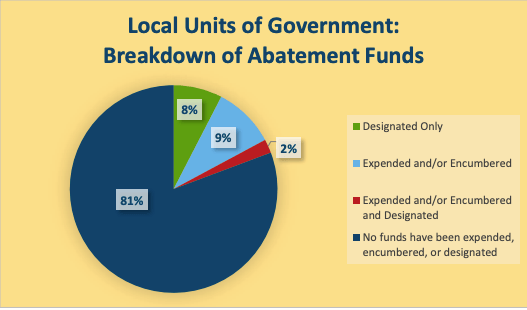

Just 606 cities, towns and counties of the 648 reported their spending to NextLevel Recovery, part of the state’s Office of Drug Prevention, Treatment and Enforcement. Of those, 81% of abatement funds hadn’t been expended, encumbered or designated. Even fewer had opted to spend unrestricted funds — 87% of cities, towns and counties hadn’t touched those dollars yet.

Though there isn’t yet a dashboard of spending, the office’s executive director, Douglas Huntsinger, hinted at a Nov. 3 meeting of the Indiana Commission to Combat Substance Use Disorder that one is coming and current reports are available at in.gov/recovery/settlement.

Huntsinger told the Indiana Capital Chronicle that individual town, city and county spending reports will be available in December and as more funds are spent, “the reports will get more complex in the future.”

Confusion erupted for the smallest towns and townships receiving paltry amounts — some too small to purchase a $45 box of Narcan — as recorded in final comments submitted to the state.

“The funds have not been spent because what can you do with $9.10?” wrote Terry Craig, the Clerk-Treasurer of Milton, a town of just over 450 in Wayne County. “We got short changed on this.”

Craig’s disbursement was one of 157 under $1,000 — all of which were clawed back and combined with a county allotment this year.

In Hancock County, Clerk-Treasurer Yvonnes Jonas found herself flummoxed at the new duty thrust upon her in a community of 2,744 Hoosiers. Her town, New Palestine, received $2,108.

“The opioid money is a very small amount. It can’t be used by our small community to start any kind of significant program,” Jonas wrote. “I am not equipped to fix the opioid crisis. The burden of this detailed reporting takes me away from more important things. I wish our town had not been burdened with this task/money.”

Jonas and 289 other towns or townships won’t receive such funds in the future. They were part of the 48% of grantees with funds below $5,000 and after July this year their portions will also be absorbed into county coffers instead.

State dollars spent on grants

In contrast to smaller subdivisions of government, the state spent nearly $19 million of its $53.7 million share, or 35% of its total funds.

Over $18.8 million of those dollars went to grant funding while $110,000 went to Hope Academy Recovery High School, a tuition-free, public charter high school in the Indianapolis area.

The state used other funds streams to bolster grants, awarding $25 million with an explicit goal to increase treatment options and programs.

Efforts have increased the number of treatment beds by 432, according to Huntsinger, who said recipients have until September 30, 2024 to complete their awarded projects.

Huntsinger, in a statement, said residences “must be completed, apply to become certified by (the Family and Social Services Administration’s) Division of Mental Health and Addiction (DMHA) and apply to become a Recovery Works provider” by that time.

“Since 2017, we have spent a lot of time trying to address quality at existing recovery residences, ensuring evidence-based practices are followed and that all forms of medication for opioid use disorder are accepted,” Huntsinger continued. “Due to the restrictive nature of other funding streams, the National Opioid Settlement grants us the first opportunity to fund capital costs, allowing for the creation of new beds.”

But a firm number of necessary beds couldn’t yet be calculated.

“This is in many ways a pilot to better understand the need for more capacity,” Huntsinger said.

Other efforts include Harm Reduction Street Outreach (HRS) Teams, for which the agency is currently accepting proposals to expand the state’s current ten teams. Between January 2022 and August 2023, existing teams have distributed 41,973 harm reduction kits and served Hoosiers across 102 zip codes.

Lessons learned from tobacco settlement

Repeated national audits of the landmark 1998 tobacco master settlement revealed that less than 3% of those dollars went to prevention and cessation.

Indiana is no exception.

Though fund totals for the Tobacco Master Settlement Trust Fund regularly top out over $210 million, budget writers divert just $7.5 million directly to the state’s prevention and cessation program between 2021 and 2023 — roughly 3-3.5% of total funding for each of those years.

Nearly all of that funding goes to local community-based partnerships and grants, according to the agency’s annual report.

The largest singular appropriation goes to the administration of the Department of Health, which oversees the fund, at $23 million. Overall, the agency gets over $90 million — much of it dedicated to other worthwhile causes, such as prenatal substance use and prevention, community health centers, the Safety PIN Program and even donated dental services.

FSSA received $74 million in 2021 but its share fell to $23 million in 2022 and 2023. It spent around $250,000 each of those years for Youth Tobacco Reduction Support programs but the bulk of its share of settlement funds goes to CHIP (a children’s health insurance program) and community mental health centers.

A smattering of others get a slice of the pie, including the Attorney General’s Office, which gets $818,916 a year, and various medical board residency programs and grants.

According to the fiscal closeout for 2023, plans for spending the money will be the same for the next fiscal cycle — even as many counties have turned to the new public health program to fund local tobacco prevention and cessation efforts.

Applying that to opioid settlement

The opioid settlement, on the other hand, specifies that 70% of funds must be spent on narrowly defined opioid-related expenses — while 15% of monies go to administrative costs or past opioid-related expenses. Only 15% of the dollars are totally unencumbered.

“The National Opioid Settlement is fundamentally different from the tobacco settlement. The opioid settlement requires that a majority of funds be used for treatment, education, and prevention programs for substance use disorder and co-occurring mental health issues,” Huntsinger said. “Similarly, the legislature is treating these dollars differently, with transparency at the forefront.”

But those funds do still have limitations set by the national settlement agreement — notably, nothing for the hundreds of thousands of Hoosiers who’ve lost a loved one to an opioid overdose or the grandparents raising grandchildren in the absence of their parents.

“Understanding that children with a loved one with (substance use disorder) are susceptible to greater risk factors, we are working with (the Division of Mental Health and Addiction)’s prevention bureau to understand how we can provide additional prevention services and programming for both children and the whole family,” Huntsinger said. “We are also having conversations with our counterparts in other states to learn how they are serving families within the parameters of approved uses.”

The full, annual Next Level Recovery Progress Report will be released at the end of the month.

This article originally appeared on Indiana Capital Chronicle.