By Grace Barbic and

Sarah Mansur

Capitol News Illinois

[email protected]

[email protected]

During the past three and half decades, Rep. Mary Flowers — who in January became the longest-serving African American lawmaker in the Illinois General Assembly’s history — has fought to pass health care reform and advocate for groups marginalized by systemic racism.

It’s a fighting spirit the 69-year-old lawmaker inherited from her mother, who worked in a factory and other odd jobs to provide for her seven children, and one that she honored while following in the footsteps of Black legislative leaders in Illinois who preceded her.

Born in Inverness, Mississippi in 1951, Flowers moved to Chicago when she was about four years old with her mother and six siblings.

She and her family were part of the Great Migration, which describes the journey made by an estimated 6 million African Americans from southern states to large northern cities, including Chicago, from 1916 to 1970.

Her family migrated north after World War II, looking for a better life and greater opportunities. But the reality in the north wasn’t always that far removed from the segregation and discrimination they faced in the south.

Flowers recalls being slapped by a nun who was teaching her class in 3rd grade because she dared to look her white teacher in the eye — something her mother taught her to do.

“And I slapped her back. Of course, my mother had to remove me from the school. Because if not, I would have stayed in third grade for the rest of my life,” she said.

That spirit has stuck with Flowers throughout her rise to her current leadership role in the Illinois House.

“I hope my legacy will be that people will remember me for trying to help someone along the way,” she said. “I would like for people to know that I gave it my best.”

Road to the General Assembly

Flowers said her family’s move to Illinois became necessary because her mother was forced to flee Mississippi after having a threatening interaction with a white man while she was working as a waitress – she remembers the name of the restaurant, the White Rose Cafe.

“This white man told my mother to get over here,” Flowers said. “And so she ignored him and he said something again. And the third time, he took his knife, and my mother was behind the bar and he threw the knife on the counter. And, of course, my mother took the knife and threw it back at him. And he tried to do something to my mother right then and there.”

Flowers said her mother managed to get out of the restaurant without any serious harm, but she said her mother knew she couldn’t stay in town that night.

“So she left and she made it to Chicago. And eventually she came back for us,” she said.

“I knew the struggles that my mother had, I saw the fights that she had to deal with every day, just to get up to go to work to keep a roof over our heads.”

Her family settled in a neighborhood on the south side where Flowers attended several different schools, including Our Lady of Solace and St. Bernard elementary school. She graduated from Simeon Vocational High School in 1970, and then attended Kennedy King Community College and the University of Illinois Chicago.

Growing up during the civil rights movement, Flowers said she was aware of the acts of civil disobedience and protest against racial segregation. The first protest she experienced was in October 1963 when she observed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in a neighborhood park where he was rallying against school segregation in Chicago.

As a teenager, she saw news coverage of Harold Washington, who at the time was a lawmaker in the Illinois House of Representatives, where he served from 1965 to 1977. She asked her mother to take her to his office so she could meet him.

She became involved in politics when she met Washington, who later was elected Chicago’s first Black mayor, and she volunteered to work on his political campaigns while he was in the Illinois General Assembly.

“I was very young and naive, and I would tell him that if I was the state representative, I would have said this, I would have done that. And he would just smile,” Flowers said.

Washington went on to serve as a state senator from 1977 to 1980, and then a U.S. congressman, before being elected mayor in 1983.

As mayor, he requested that Flowers visit him in his new office in downtown Chicago. At the time, Flowers was working and taking classes at UIC, and she doubted that a man with such prestige would remember her by name.

“I’ll never forget, it was so humbling. It was like I was walking in on, you know, someone very godlike,” she said. “He said have a seat and he said to me, the purpose of this meeting is to let you know that I want you to run for state representative.”

Flowers was in disbelief and insisted that she wasn’t capable. But Washington reminded her of her volunteer days, when she would talk about how she would’ve led differently.

In November 1984, with Washington’s endorsement, Flowers was elected state representative for the 31st District, which contained the south side community where she grew up.

In January, she began serving her 19th term in the Illinois General Assembly and witnessed the inauguration of the state’s first Black speaker of the House, who appointed her deputy majority leader. She is also a member of leadership in the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus.

Following a legacy of trailblazers

When Flowers arrived in the Illinois General Assembly in 1985, she was one of seven Black female lawmakers, all of whom she considered her mentors.

Among Flowers’ peers was Carol Moseley Braun, who went on to be the first Black woman elected to the U.S. Senate in 1992, and Earlean Collins, who was the first Black woman elected to the Illinois Senate.

“I like to think that we were able to make a difference in policy because that’s, after all, why we were there, is to make a difference on policy and to bring our lived experiences to the conversations about policy that the General Assembly took up,” said Braun, who served in the Illinois General Assembly from 1979-1988. “So, I am very proud of her.”

Flowers cited other Black female pioneer lawmakers as role models, including Ethel Skyles Alexander, Monique Davis, Wyvetter Younge and Margaret Smith.

Another role model was Sen. Charles Chew, one of the cofounders of the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus, who would share stories about how Black lawmakers could not eat in the restaurants or even stay in hotels when they drove to the capital city. They would pay residents out of their own pocket to stay in their homes.

“I try to tell those stories to others, to all of my colleagues that have come behind me to always remind myself and to be the one to tell them the story that someone told me about how we all got here, and the struggles that we had to go through so that we could be where we are today,” Flowers said.

“If it wasn’t for Sen. Chew, Harold Washington, and so many others in the past, whose shoulders I stand on…they put a crack in the wall,” Flowers said. “Hopefully I put a crack in the wall for my colleagues as they are now. And maybe one day, the wall of racism and inequality and inequity will be totally knocked down.”

A younger generation of lawmakers view Flowers as a role model. Among them is Lt. Gov. Juliana Stratton, who served with Flowers in the House from 2017 to 2019. She said she considers Flowers “one of those trailblazing women that really fought to be in the state legislature.”

“I feel like her work and her presence really paved the way for me, and was inspiring for me when I ran for state representative, but it also paved the way for women like (Vice President) Kamala Harris to be in the positions that they are in,” Stratton said.

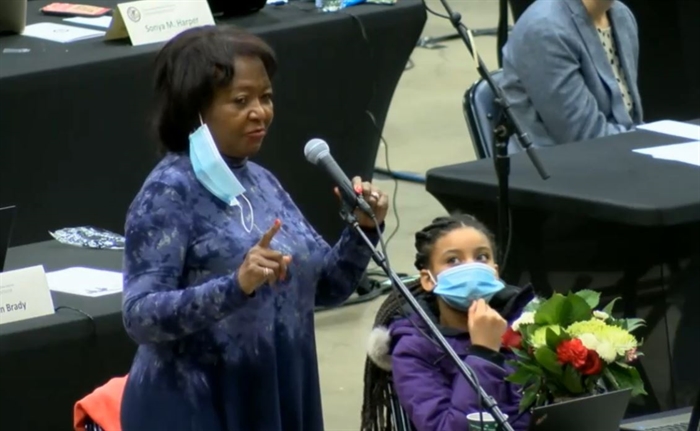

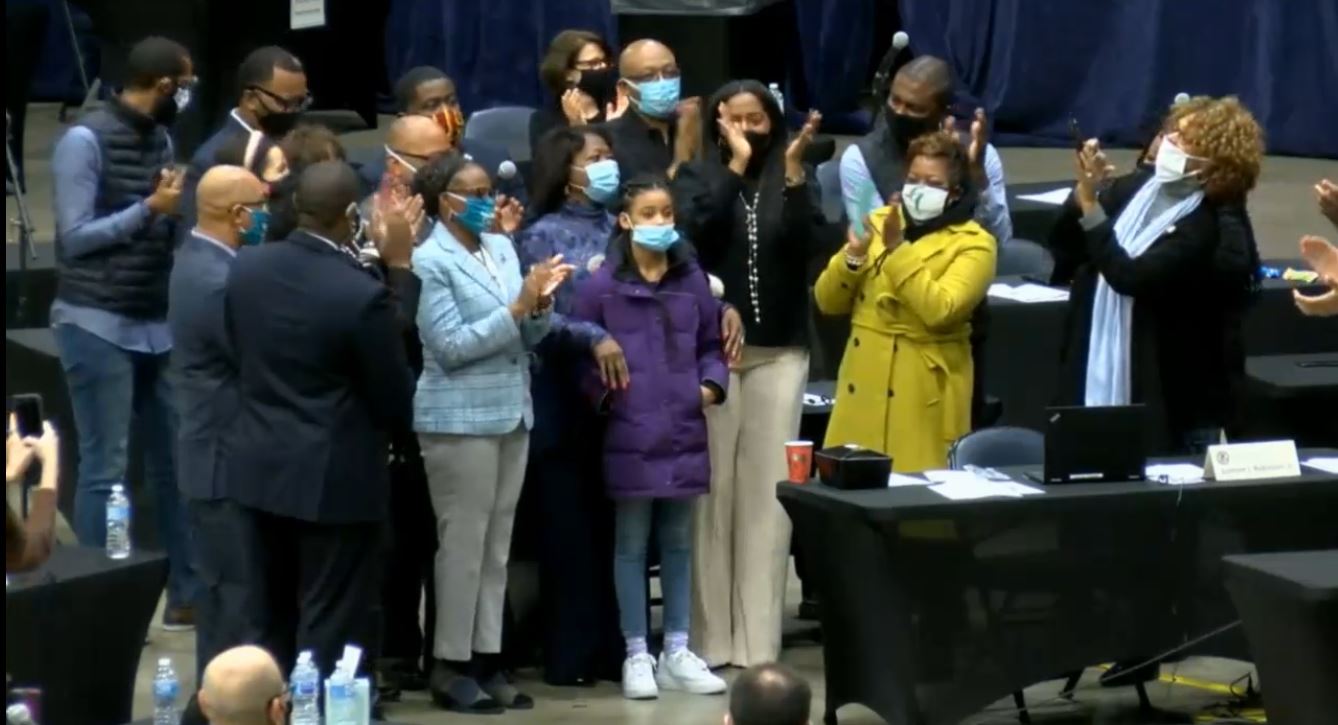

Flowers was honored by newly-seated Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch – the first Black lawmaker to hold that title – during the 102nd General Assembly’s inauguration for her longevity in the General Assembly. In a floor speech, Rep. Rita Mayfield, D-Waukegan, referred to her as “the glue that has kept the Legislative Black Caucus together.”

Rep. LaShawn Ford, D-Chicago, echoed that sentiment.

“Without Mary Flowers there would probably be no Emanuel ‘Chris’ Welch as speaker,” he said.

Health care legacy

Flowers cites her work on health care reforms as her proudest legislative accomplishments.

“It’s those types of bills that have been able to help so many people, so many people at one time all across the state, regardless of your zip code, regardless of the color of your skin, regardless of income. To me, there are certain things that we just should have been entitled to,” Flowers said of her belief in a human right to health insurance.

The year before Flowers was named chair of a House committee on health care availability and access, she championed a law that ended a practice known as “drive-through deliveries,” in which hospitals discharged women sometimes hours after childbirth.

When then-House Speaker Michael Madigan announced the creation of the new committee in January 1997, he said it would be tasked with, among other things, addressing the “abuse” by HMOs, or health maintenance organizations — a health care system in which subscribers pay a set fee for benefits.

At that time, Flowers was aware of the ways HMOs cut costs by denying necessary health care coverage to individuals. She heard horror stories where patients were denied medical care by the HMOs, which put doctors under “gag rules” preventing them from discussing treatment options with patients.

Following years of negotiating, Flowers struck a compromise with the major stakeholders in the health care and insurance industries to advance the first major HMO reform in Illinois, the Managed Care Reform and Patient Rights Act, which passed in August 1999.

The law prohibits gag rules, requires HMOs to explain when an individual’s claim for coverage is denied, and provides a process to appeal an HMO’s coverage decision.

Although the law did not specifically establish a patient’s right to sue, the Illinois Supreme Court recognized that right in a court case that was decided less than a year after it passed.

The May 2000 opinion, authored by Illinois Supreme Court Justice Michael Bilandic, decided for the first time that HMOs could be held financially responsible for institutional negligence.

Flowers said she received a phone call from Bilandic after that decision. He told her that her discussion of HMOs in the House helped shape his understanding of the issue, and her comments influenced his decision in that case.

“And to me, I was doing what I was supposed to do. That’s why God put me in the House,” she said.

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government and distributed to more than 400 newspapers statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.