In a historic ceremony that was long overdue, President Joe Biden on Tuesday, March 29, signed into law legislation that makes lynching a federal crime anywhere in the nation’s 50 states.

The relatives of Emmett Till and the late journalist Ida B. Wells joined civil rights leaders in the Rose Garden at the White House where President Biden signed Congressman Bobby Rush’s bill that passed the House and the Senate in March.

It was the end of a long battle in Washington that took more than a century to achieve. Today, over 200 bills later, lynching is now a federal hate crime in America.

Between 1877 and 1950, more than 4,400 Black people were murdered by lynching, most in the South. As the lynchings piled up, Congress rejected bill after bill that aimed to make lynching a federal crime.

“That’s a lot of folks, man, and a lot of silence for a long time,” President Biden said during the ceremony with Vice President Kamala Harris by his side.

“Lynching was pure terror to enforce the lie that not everyone — not everyone belongs in America and not everyone is created equal; terror to systematically undermine hard-fought civil rights; terror not just in the dark of the night but in broad daylight.”

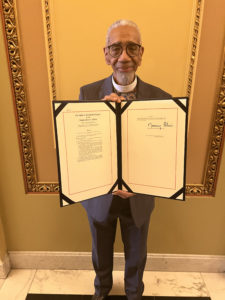

Till’s cousins, Ollie Gordon and Reverend Wheeler Parker Jr., and Wells’ great-granddaughter, Michelle Duster, and Congressman Bobby Rush were present as Biden signed the historic legislation into law.

“To the Till family: We remain in awe of your courage to find purpose through your pain,” Biden said. “But the law is not just about the past, it’s about the present and our future as well.”

“This is a historic day and a day of enormous consequence for our nation. After more than 100 years and 200 attempts, lynching is finally a federal crime in America,” Congressman Rush said.

“When I think of what this means — that we can finally provide justice for the victims of this heinous act; that we will be able to reckon with our nation’s legacy of lynching; and that we will, once and for all, send a strong message that we will not stand for these abhorrent crimes — I am elated.

“The enactment of my bill means that the full weight and power of the United States government can be brought to bear against those who commit this vicious crime. We will no longer face the question of if a perpetrator of lynching will be brought to justice — with the President’s signature today, we have eliminated that possibility moving forward.”

President Biden drew applause when he said, “Over the years, several federal hate crime laws were enacted, including one I signed last year to combat COVID-19 hate crimes. But no federal law — no federal law expressly prohibited lynching. None. Until today.”

It was over 100 years ago, in 1900, when a North Carolina Representative named George Henry White, the son of a slave and the only Black lawmaker in Congress at the time, who first introduced legislation to make lynching a federal crime. The bill would be one of 200 that would fail in either branch of Congress.

In February 2020, the House Bill H.R. 55 passed the House of Representatives during the 116th Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support but was blocked in the Senate. Congressman Rush reintroduced the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act on the first day of the 117th Congress and worked closely with the House Judiciary Committee and the Senate throughout the past year to reach an agreement on the text of the legislation.

The bill passed the U.S. House of Representatives on February 28 by a vote of 422–3 and passed the U.S. Senate unanimously on March 7.

“When I think of what this means… I am elated… This bill is a victory for the city of Chicago, a victory for America, and a victory for Black America in particular,” Congressman Rush said.

The Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act designates lynching as a federal crime — specifically, a federal hate crime — for the first time in U.S history and defines lynching as a conspiracy to commit a hate crime that results in death or serious bodily injury. More than 6,500 Americans were lynched between 1865 and 1950, according to a recent report from the Equal Justice Initiative.

H.R. 55, the legislation that was signed into law, differs from the antilynching legislation passed during the 116th Congress in two primary ways:

• The maximum sentence for a perpetrator convicted under the Anti-Lynching Act is 30 years; the previous version of the legislation set the maximum sentence at 10 years.

These charges would be in addition to any other federal criminal charges the perpetrators may face.

• The legislation applies to a broader range of circumstances. Under the legislation passed last Congress, a crime could only be prosecuted as a lynching under very specific circumstances, such as if it took place while the victim was engaging in a federally protected activity.

The bill is named after Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood, who was killed by two white men in 1955 in Money, Mississippi. He was accused of whistling at Carolyn Bryant Donham, a white woman whose husband, Roy Bryant co-owned the grocery store where she worked.

Roy and J.W. Milam killed Emmett and threw his body into the Tallahatchie River.

A fisherman later found the bloated body that was tied to a fan with barbwire. The teenager had a bullet hole in his head, which was left severely disfigured from brutal beatings.

Till’s killers were later acquitted of murder in a trial that lasted just over one hour. Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, held an open casket funeral in Chicago to show the world what the two men had done to her son. Jet magazine published photos of Emmett’s body before major newspapers followed suit.

Mobley died in 2003 and is buried at Burr Oak Cemetery, where Emmett’s remains are also interred.

“I am thinking of Emmett Till, who would have been 80 years old today. His brutal lynching ignited the Civil Rights Movement and a generation of civil rights activists. It had a ripple effect that we still feel today; it began a worldwide movement to reckon with freedom, justice, and equality all around the world.

“Emmett Till meant so much to the city of Chicago. The signing of this bill is a victory for the city of Chicago, a victory for America, and a victory for Black America, in particular. I am so proud that we have come together — in a bipartisan fashion — to enact a law that will ensure lynchings are always punished as the barbaric crimes they are.”

Rush is also the lead sponsor of bipartisan legislation that would award a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal to Emmett Till and his mother Mamie Till-Mob- ley (H.R. 2252) and legislation that would direct the Postmaster General to issue a commemorative postage stamp in honor of Mamie Till-Mobley (H.R. 4581).