Photo caption: Harry Belafonte

Harry Belafonte, who was known as much for his Civil Rights activism as his acting and singing, died on Tuesday, April 25, in his Manhattan, New York, home.

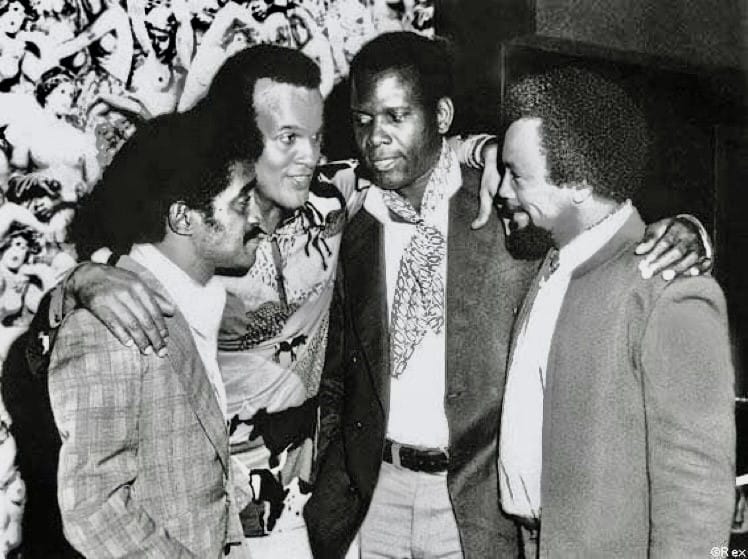

Belafonte climbed the ladder to Hollywood stardom in the 1950s, along with his lifelong buddy, Sidney Poitier, but he went on after a few films to make an indelible mark on justice for Blacks throughout the nation through various movements during his decades of activism. With both men gone, it’s hard to separate the two.

Belafonte once said about Sidney, when that icon died in early 2022: “Sidney and I laughed, cried and made as much mischief as we could. He was truly my brother and partner in trying to make this world a little better. He certainly made mine a whole lot better.”

Belafonte’s daughter, Shari, told People Magazine last year: “Losing Sidney is probably the most difficult thing my father has had to fathom, more so than losing Martin L. King. They have known and loved each other for more than 70 years, collaborating, living life to the fullest. …Harry was much more vocal and seemingly more instrumental in the Civil Rights Movement via his stage presence and his navigating the dynamics between leaders and politicians.”

Belafonte once admitted as much: “I wasn’t an artist who’d become an activist,” he was quoted as saying. “I was an activist who’d become an artist.”

This activism drew him to Chicago many times. This writer recalls meeting him at a book reading in 2012 at the Union League Club, as he read from his book My Song. The pastor of St. Sabina, in a news interview on April 25, spoke of his fondness for Belafonte.

Father Michael Pfleger told ABC7 News, “He never let go of that determination to continue Dr. King’s legacy for justice for the beloved community,” as he explained that Dr. King’s passion for social justice brought him and Belafonte together.

Besides King, Pfleger said that Belafonte was his greatest influence. “He helped shape me. It is my belief today and my fight today for justice and who I am today. The good, the bad and the crazy has been shaped by him so much.”

Belafonte even celebrated his 90th birthday in 2017 at St. Sabina, where he mixed humor, humility and humanity. “He had such a gentleness and peacefulness and love about him. And yet he was so bold and so strong and so courageous in what he believed.”

Native Chicagoan and artist, songwriter and television producer Quincy Jones tweeted: “RIP to my dear brother-in-arms, Harry Belafonte. From our time coming up, struggling to make it in NY in the 50’s with our brother Sidney Poitier, to our work on “We Are The World” and everything in between, you were the standard bearer for what it meant to be an artist/activist.

“For those who had no voice and those who seemingly had no hope, you made the world a better place, Harry, and there can be no higher calling than that. God Bless you and please give our other brothers a long-awaited hug from me as well.”

“We are all saddened by the passing of Harry Belafonte, who was once known as the Calypso King for his singing, but blazed a trail as a generational figure, boldly engaged with the Civil Rights Movement,” Charles Coleman, Film Program Director, FACETS, told the Crusader. “He supported many humanitarian causes and used his fame to advance the struggle for Black freedom, and many of his films also endorsed his beliefs.

“Over the years he organized demonstrations, raised money and contributed his personal funds to keep movement activities going. His career demonstrated a commitment to send light into the darkness of men’s hearts and believed that this was the duty of an artist, as well as to spend your life in a constant state of rebellion.”

These films to which Coleman refers include those featuring Belafonte that spanned decades, beginning with the 1954 “Carmen Jones,” where he starred with Dorothy Dandridge and an all-Black cast. The pairing guaranteed sultry scenes between the two—he a tall, handsome man, and Dandridge who would eventually be known for making even a glacier melt as she sauntered across Hollywood stages.

In between were his star turn in “Odds Against Tomorrow,” where he played a husband who is down on his luck and gets involved with a bank heist—with one of the partners turning out to be a bigot. Other films included “White Man’s Burden,” “Calypso Dreams,” and films accompanied by his buddy, Poitier, which included “Buck and the Preacher” and Uptown Saturday Night.”

Belafonte caused an uproar in early April 1968 when British artist Petula Clark touched his arm during a television special. All hell broke loose. At that time, he was a Grammy-winning singer, whose signature tune, “The Banana Boat Song,” brought calypso music to a mainstream audience.

An executive with the Chrysler Corporation, the program’s sponsor, aggressively protested and turned this “touch” into what one critic would eventually call “an interracial cause célèbre.”

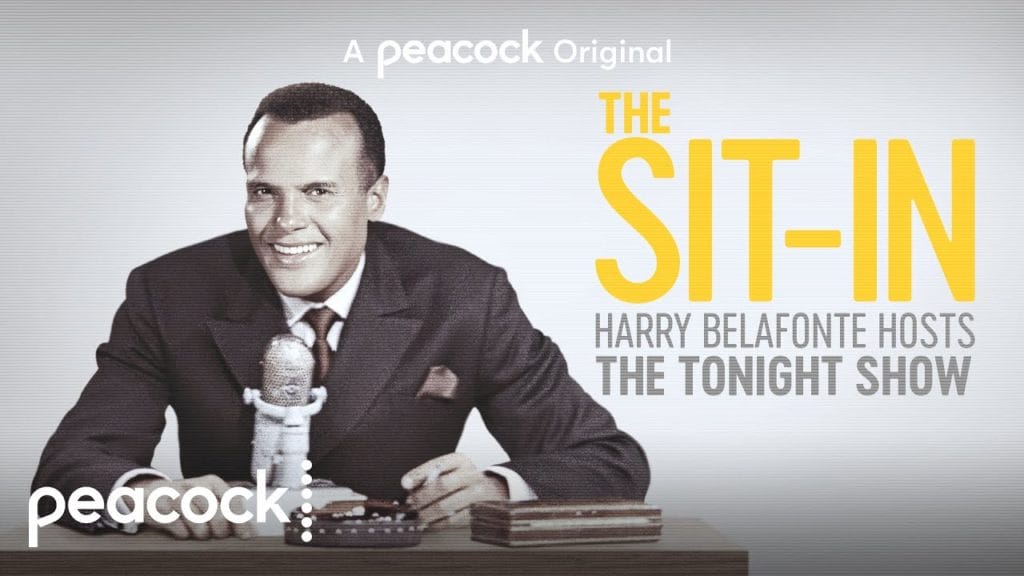

Shortly before that during Black History Month, the late television host Johnny Carson welcomed Belafonte to take over his nightly show for a week. I considered this a coup for the community, since we had never ruled late night—either behind the desk or on the stage. America was in the midst of one of the most tumultuous periods in its history, during a major escalation of the Vietnam War, and with social protests dominating the newscasts.

“America needed to see what we were struggling with as a people of color. Art without content is not art. My job was to bring the best that Black America had to offer,” Belafonte said. “We could no longer tolerate racial indiscretions. The Black community had risen up with righteous indignation. As perfomers, we felt that we needed to speak out. America needed to see what we were struggling with as a people of color.”

In “The Sit-In: Harry Belafonte Hosts The Tonight Show,” a week of episodes showed mainstream America “a whole new group of Black artists they had never heard before.” Black celebrities and those sympathetic to the Civil Rights Movement were presented in all their glory.

Each episode began with Belafonte singing a song, and the Peacock documentary reveals that not all the guests were Black. The late Senator Bobby Kennedy was one of the guests. Belafonte had considered Kennedy an elitist and out of touch with the plight of Black folks, and he suggested that Kennedy travel Down South to see how poor Black people live; he gave Kennedy an outlet to present his insight about that visit.

Guests included, among others, Wilt Chamberlain, Freda Payne, Dionne Warwick, Lena Horne, Diahann Carroll, Aretha Franklin and Poitier, as Belafonte introduced “a fractured, changing country to itself for five historic nights.”

Dr. King hadn’t been on television much, and when Belafonte booked him, NBC network big shots asked whether Dr. King was going to discuss “that civil rights stuff,” to which Belafonte answered, “That’s a silly question. What would you like him to do, sing a song?”

Dr. King’s daughter Bernice tweeted: “When I was a child, #HarryBelafonte showed up for my family in very compassionate ways. In fact, he paid for the babysitter for me and my siblings. I won’t forget…Rest well, sir.”

Author, activist Cornel West tweeted: “I am deeply sad at the loss of my very dear brother – the great Harry Belafonte! His artistic genius, moral courage and loving soul shall live forever! God bless his precious family!”

Writer, and civil and human rights activist Kevin Powell posted: “Harry Belafonte is one of my greatest heroes, a social justice-centered artist and human being and man I’ve patterned my own life after, especially because I had no father or father figure in my early years of being an activist and writer. His work is done. May he rest peacefully.”

Belafonte also starred in numerous Broadway productions, and he almost single-handedly ignited a craze for Caribbean music with hit records like “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” and “Jamaica Farewell.” His album “Calypso,” which contained both those songs, reached the top of the Billboard album charts shortly after its release in 1956 and stayed there for 31 weeks.

During his lifetime, Belafonte earned BET and NAACP Awards, three Grammys, and an Emmy and a Tony Award. He received Kennedy Center Honors in 1989, the National Medal of Honors in 1994, and in 2022 was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the Early Influence category.

Ironically, in 1970, Belafonte played an angel in the film “The Angel Levine,” where he is commanded to shore up another man’s belief in God in order for Belafonte to gain his angelic wings. May Belafonte rest in peace and power.

Born in Harlem to West Indian immigrants in 1927, Belafonte lived in Jamaica and returned to New York in 1940. He also served time in the U.S. Navy. He was married and had four children.

Elaine Hegwood Bowen, M.S.J., is the Entertainment Editor for the Chicago Crusader. She is a National Newspaper Publishers Association ‘Entertainment Writing’ award winner, contributor to “Rust Belt Chicago” and the author of “Old School Adventures from Englewood: South Side of Chicago.” For info, Old School Adventures from Englewood—South Side of Chicago (lulu.com) or email: [email protected].