Residents in McKinley Park have lodged 367 complaints against a politically connected city developer who they say have ignored their complaints about ongoing toxic pollution that perfumes the air with a scent reminiscent of “rotten eggs and fireworks.”

But now that the federal government has ruled that Chicago’s Black and Latino residents are routinely subjected to environmental racism, McKinley Park residents are hopeful relief may be in sight. This week, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) told Mayor Lori Lightfoot that Chicago is creating “sacrifice zones” and putting many of its residents of color in harm’s way.

In a letter made public Tuesday, HUD said Chicago has a “broader policy of shifting polluting activities from White neighborhoods to Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, despite the latter already experiencing a disproportionate burden of environmental harms.”

One of those neighborhoods in McKinley Park. MAT Asphalt, located at 2055 W. Pershing Road, opened in 2018 and almost immediately became the subject of complaints from residents who’ve called on the state and city to close the facility. The neighborhood, located on the Southwest Side of the city, is home to mostly working-class Latino, white, and African American residents.

Antony Moser, a resident/activist with the Neighbors for Environmental Justice (N4EJ) told the Crusader, “You can’t open a window or run an air conditioner because of the nasty smell. Its unbearable–sort of like a combination of rotten eggs and fireworks. There’s a lot of sulfur and it sort of hangs in the air.

“It’s not only that,” Moser told the Crusader, “in addition to the fumes which make it difficult to breathe, there’s the roaring of these trucks, which also emit fugitive emissions. The plant is within 1,000 feet of a school.

N4EJ organized soon after MAT Asphalt opened shop in their neighborhood—long before the embarrassing debacle that saw a ominous Black cloud spread over the Little Village neighborhood during an unexpected, unannounced early-morning demolition. Other activists have decried the move of General Iron from the city’s toney Lincoln Park neighborhood to a predominantly Black and Hispanic community.

The McKinley Park group’s call for public hearings on the matter have also been ignored—though residents were able to get the attention of U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth, who has reportedly made an inquiry into the matter.

Moser said MAT Asphalt was operating illegally and without a permit. The Crusader reached out to co-owner Michael Tandin, Jr. who did not respond to inquiries by Crusader deadline. However, the developer has publicly accused of exaggerating their claims.

On the company’s website it notes their facility is “one of the most modern asphalt pavement-making facilities in the nation…. The technology in place at our facility controls emissions. Consistent with the federal Clean Air Act, the IEPA permit placed limits on emissions of materials from our facility, including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, sulfur dioxide and volatile organic material. Our facility, which is subject to performance testing by the IEPA to ensure compliance, operates well within emissions requirements.”

In January of this year, Tandin released his own report that noted emissions from materials such as arsenic, manganese, formaldehyde, benzene and other toxic chemicals are low. The company’s consultant noted that levels of hazardous, cancer-causing air pollutants were within the allowable range.

Air pollution is monitored by a few governmental agencies including the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (ILEPA) and the city’s Department of Public Health.

ILEPA received a series of questions Wednesday and spokesperson JC Fultz said, “We received your questions and are working on getting you answers. Unfortunately, I don’t think we will be able to get you anything by (close of business) today. We will work to get you answers as soon as we can.”

The city’s press office also did not respond to questions before this paper’s deadline. However, in June the City of Chicago rejected bids for citywide asphalt production, including a $500 million bid from Tandin’s limited liability company. There was no indication if the multitude of residential complaints played a role in the decision.

The Tandin family name is no stranger to controversy. His father, Michael Tandin Sr., is a politically connected developer from Bridgeport who was caught up in the city’s hired truck scandal in 2004. Federal authorities alleged Tandin’s company, among others, received money for work that was rarely performed, were connected to organized crime, or were charging smaller, minority contractors a fee to participate in the public program as a sort of pay to participate scheme.

However, despite a dubious history with city contracts, data suggests that companies connected to the Tandin clan have blossomed under Lightfoot’s administration. “Contractors like Michael

- Tandin and his family have spent decades making millions from city government by polluting city residents,” said Moser. “And, under Mayor Lightfoot they’re making more money than ever.”

In a public dashboard created by environmental activists, the Tandin family earned $44 million during Daley’s leadership. However, since Lightfoot took office nearly four years ago, the contractors are well on their way to surpassing that amount. “Under Mayor Lightfoot, in 20202 alone, they were paid $30.8 million. There were over a hundred payments, with about a third of the money coming from the Chicago Department of Transportation, another third coming from the Department of Water Management and most of the remainder from Streets and Sanitation.”

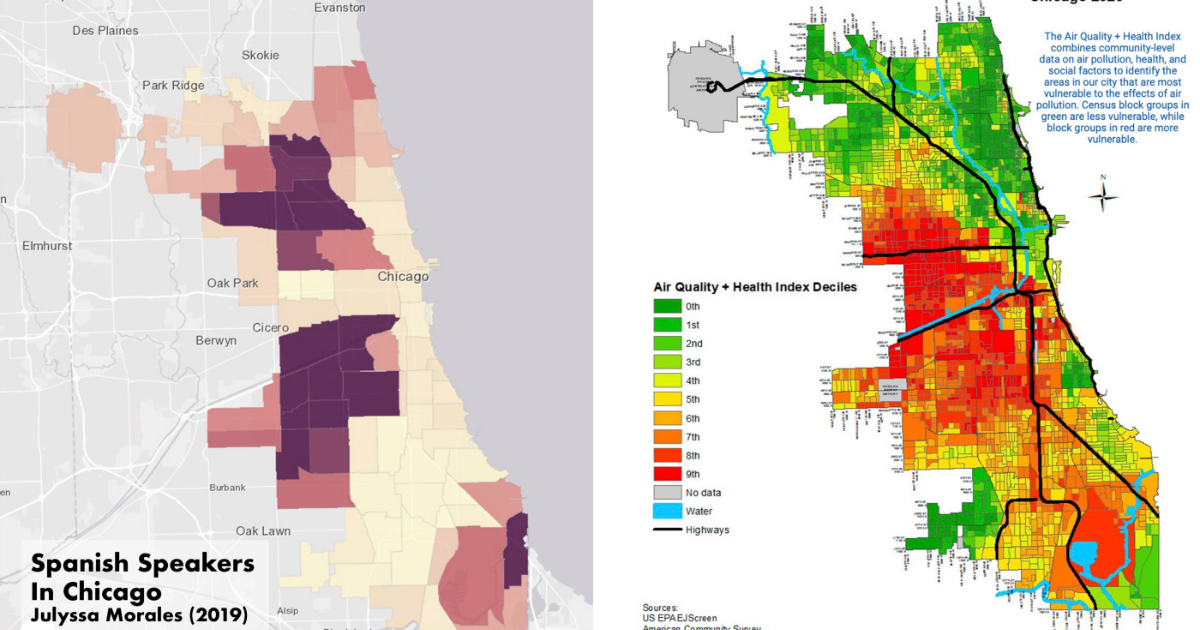

Despite the complaints, MAT Asphalt does not appear phased by the complaints or the reported $4,000 in fines it was raked up in recent months. Moser said, it should also be noted that the City has also made it harder for second language residents to file complaints. Air pollution cases may be under-reported. “In Chicago, many of the communities with the worst air quality have large Spanish speaking populations — McKinley Park also has growing numbers of Chinese speakers,” he said. “And, yet the IEPA has English-only complaint forms, preventing people who are most affected by the problem from reporting it. This is what environmental racism looks like.”

This week’s letter from HUD received praise from local environmental activists, many of whom have united under the umbrella of the Chicago Environmental Justice Network.

“The tide of segregation and environmental racism in Chicago has been devastating Black and brown communities for far too long,” the groups said in a joint statement released to the press. “This federal investigation from HUD shows without a doubt that systemic racism in Chicago is creating sacrifice zones and putting the most vulnerable in harm’s way. All eyes are now on the Mayor’s office and City Council to take accountability and end the systems that allow the dirtiest industries to pile up in our communities.”

This report is supported in part by the Inland Press Foundation.