By Stephanie Gadlin, Special to the Crusader/Inland Foundation Fellow

Special to the Crusader – Part I

Provisions in the new criminal justice reform legislation will take effect on January 1, 2023. Not only has it stoked hope among African Americans that relief from years of disparity and injustice are on the horizon, the legislation has also spurred a sort of panic that roving bands of criminals will be given the green light to run amok without fear of arrests and incarceration. Such fears are equally historical as they are rooted in this country’s racist past.

The Illinois Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity-Today (SAFE-T) Act, which Governor J.B. Pritzker signed into law in January 2021, ends the use of cash bail, sanctions new limits on police use of force, and allows judges to override sentencing minimums.

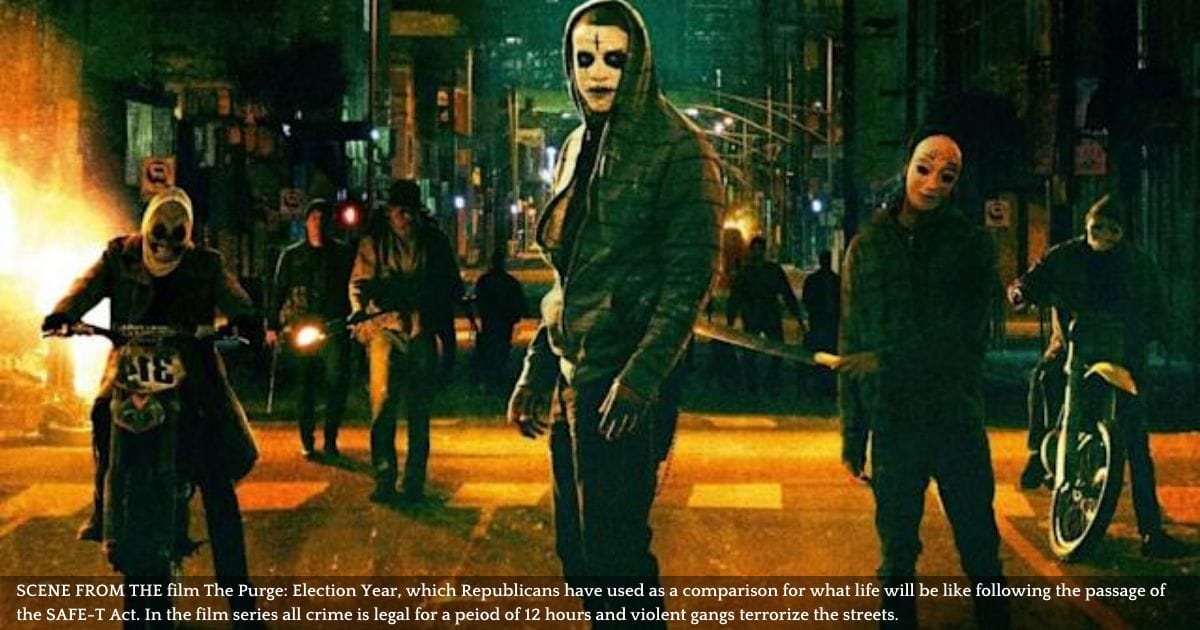

As political candidates and incumbents move into the midterms, the legislation has become fodder for Republican candidates who have likened the bill to the film, “The Purge.”

“The Purge” is a dystopian movie about a U.S. holiday that allows citizens to engage in violent crime–including rape and murder–for 12 hours without fear of punishment or interference by police, fire or other first responders. “Chicago is living ‘The Purge,’” claimed Governor Pritzker’s Republican challenger, State Senator Darren Bailey, a downstate lawmaker and MAGA supporter. “With his SAFE-T Act, J.B. is set to unleash the purge in neighborhoods all over Illinois as of Jan. 1.”

Senator Bailey’s comment sparked an avalanche of rhetoric and propaganda that has citizens and even out-of-state multi-millionaire podcasters warning Illinois citizens of what is alleged to come. The racially-charged propaganda caused elected officials and bond reform advocates to go on the offensive in a coordinated campaign to correct the scary narrative.

“The SAFE-T Act is designed to keep murderers, and domestic abusers, violent criminals in jail,” said Governor Pritzker, noting that the new law will combat disparities in incarceration. “We’re also addressing the problem of a single mother who shoplifted diapers for her baby, who is put in jail and kept there for six months because she doesn’t have a couple of hundred dollars to pay for bail.”

Still, Governor Pritzker’s words have not stopped Senator Bailey from evoking racial stereotypes about Chicago’s public safety issues by blaming Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Cook County s Attorney Kim Foxx, both of whom are Black. Leaders of the Illinois Black Legislative Caucus- a body who championed the law–have been hard at work holding town hall meetings and discussions with constituents to dispel the myths and correct the narrative.

State officials have noted that in addition to sweeping reform measures, the SAFE-T Act also regulates data collection requirements, which can assist the public in holding officials accountable for implementing the law in their local jurisdictions.

It is a sweeping bill that covers three areas of criminal justice reform —policing, pre-trial and corrections (jails and prisons). In addition to allowing the Illinois Attorney General to investigate and initiative civil suits against police agencies, the law also creates a statewide decertification process for officers; creates stricter body camera regulations and a Class 3 felony for clear and willful attempts to obstruct justice; and allows for investigation of anonymous complaints against law enforcement officers.

Whether or not the SAFE-T Act, along with local reform measures implemented in Chicago will make citizens feel safer or more secure when dealing with police, will be determined. But how did we get here?

Have Black people been the strongest voices advocating for criminal justice reform? Yes. As citizens, African Americans also want to feel safe in their homes, workplaces and neighborhoods, but at the same time, do not want their lives persecuted and surveilled by the system.

Even as a Black man successfully challenged Chicago’s gun laws resulting in today’s concealed carry, tens of thousands of others were decrying abusive policing, unjust arrests and the seemingly slow resolution when crime victims are Black.

In places, such as New York City, which recorded 485 murders last year, Black activists took on (then) mayors Rudy Giuliani’s and Michael Bloomberg’s unconstitutional stop-and-frisk campaigns, which resulted in mass incarceration and police/citizen hostility among Blacks and Latinos. That policy was born out of the state’s Rockefeller Laws, which ironically, were championed by Black leaders as a means to curtail drug and crime plaguing their communities. Other critics noted that these sorts of policies failed to reduce crime and only amounted to organized harassment.

Before the destruction of high-rise public housing in Chicago, some African Americans supported the federal One Strike law that targeted tenants in Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) properties. On March 28, 1996, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Housing Opportunity Program Extension Act, which established the legal foundation for the “One Strike and You’re Out” policy in public housing communities across the nation.

The measure allowed public housing authorities to evict tenants for such things as alcohol consumption or petty crime committed by someone in the home or a guest visiting the unit. An entire household could be evicted or denied housing if a housing authority has reasonably determined that any member or guest of a household is engaging in illegal drug use (such as smoking weed) or other activities (such as playing loud music) that interfere with other residents’ enjoyment of the public housing community.

“Make no mistake about it; in public housing, drugs are public enemy number one. We must have zero tolerance for people who deal drugs. They are the most vicious, who prey on the most vulnerable. They are the jailers, who imprison the elderly. They are the seducers, who tempt the impressionable young. They must be stopped. ‘One Strike and You’re Out’ is doing just that.” said then-HUD Secretary Andrew Cuomo in June 1997.

In 1999, the city’s anti-loitering legislation was ruled unconstitutional and celebrated as a “meaningful victory for young men of color in Chicago and across the nation,” by the American Civil Liberties Union. The 1992 law, born out of the “tough on crime movement,” had allowed police to surveil and target people suspected of gang affiliation for arrest if observed congregating in groups of two or more. It was not lost on historical observers that the anti-loitering measure was reminiscent of another policy enacted in slavery which banned two or more enslaved people from meeting for fear (by their owners) of planning insurrection.

So, how did we get here, and will the SAFE-T Act withstand the racist attack from the right? Governor Pritzker must hold a delicate balance of ensuring justice and fairness in the state’s criminal justice policies, while simultaneously being seen as taking decisive action to reduce crime and ensure public safety. But how does a “war on crime, poverty or drugs” turn into an all-out war on Black people?

The various combative campaigns launched by presidential administrations have included attacks on poverty, crime and drugs. While each begins with assurances of taking holistic approaches to complex problems, most wind up creating punitive policies that have a swift and disparate impact on Blacks.

A Crusader historical analysis shows that whenever Blacks secure relief, gains or policy wins against injustice or to ensure rights, the system follows with retribution measures that are often cloaked as moral legislation designed to secure public safety. Nearly all of these crime crusaders have roots in the Black Codes, official and unofficial code to deal with the newly-emancipated Blacks in their new citizenship.

The Black Codes, later known as Jim Crow laws, were post-Civil War legislative initiatives in the southern United States designed to enforce racial segregation and curtail the power of Black voters. These laws, which sprung up in 1865, severely limited the rights of Black people and spawned a prolific wave of murder, through lynchings, capital punishment and benign neglect.

Part II- Next week

Reporting made possible by the Inland Foundation.