By Stephanie Gadlin, Special to the Crusader/Inland Foundation Fellow

Part III

The more things change

In 1969, President Richard Nixon, who himself would be run out of public office for criminal acts, took measures to decrease the federal government’s role in providing social safety nets.

In 1969 and ’70 his Republican administration created many of the draconian sentencing laws, loosened federal oversight of local police departments and incentivized private prison construction. His measures came just as African Americans were fighting for (and winning) affirmative action and equity in hiring in federal agencies.

By December 1969, leader Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, would be assassinated by Chicago police officers under the supervision of the Cook County State’s Attorney.

The murder became another stark reminder of the sickening relationship between Blacks and local police—made worse if the victim was an activist fighting for justice or rights. But even the international shame brought upon the nation in general and Chicago in particular would not halt U.S. policing policies.

By the mid-1970s, LEAA morphed into a standalone federal agency administered by the Justice Department and more than $10 billion were placed into various crime control programs during its existence.

Its work laid the foundation for the prison industrial complex, a labyrinth of law enforcement agencies, judges, prosecutors, public defenders, defense attorneys and a host of judicial and carceral employees who facilitate, manage and administer justice.

In 1974 Congress enacted the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act in a lopsided effort to ease the flow of children and teenagers into the adult corrections facilities. This measure led to thousands of youth being “mislabeled” accidentally on purpose and stigmatized with records that would follow them for the remainder of their lives.

By this time, the federal government had fully divested in the War on Poverty and had shifted its weight to fighting crime.

Senator Daniel P. Moynihan (D-NY) did his best to advance a number of racist and biased social theories that further criminalized Blacks, especially those who were poor and living in America’s slums. The senator supported the notion that some negative behaviors found among some Black people were because they were genetically predisposed and had “lower IQs.” Before joining the Senate, in 1965 he authored the racist “Negro Family: The Case For National Action,” (aka the Moynihan Report) as an assistant labor secretary.

President Jimmy Carter was elected in November 1976. Upon taking office he redirected the nation’s attention to threats abroad and attempted to end the domestic War on Crime as it had been waged. He wanted to move closer to Johnson’s original proposals to eradicate poverty, but his efforts also had an adverse effect. His administration placed significant focus on America’s housing ‘projects’ which led to the Public Housing Security Act.

This measure, according to Prof. Hinton, called for training public housing residents, especially unemployed youth, on how to develop unarmed resident patrols, and develop surveillance and other crime fighting techniques.

Developments, such as Robert Taylor Homes, on the city’s South Side, received over $5 million, most of which went toward installing security cameras and other anti-crime measures, though it offered youth the opportunity to work on minor building maintenance projects and as security aides.

President Carter had also moved to cut federal criminal justice programs that he believed had only made social problems worse.

The president also ordered massive staff reductions in the Department of Justice and attempted to dismantle LEAA, but was unsuccessful. His plans to restore balance to U.S. criminal justice policy and address urban blight were cut short when he lost re-election to Reagan in 1980.

When LEAA was finally disbanded in 1981, it was replaced by President Reagan’s War on Drugs, a campaign that arrived just as Blacks were turning their attention to access to capital and redlining by banks. This punitive campaign was said to be in response to the cocaine and crack epidemic that was sweeping the nation. Nightly news was filled with vivid reports of ‘crackheads’ and gangs holding everyday Americans hostage. The loudest cries were coming from those most impacted, Black families trapped in neighborhoods with rampant disinvestment.

It would be more than a decade later when it was alleged by reporter Gary Webb at the San Jose Mercury News that U.S. intelligence and military agencies played a significant role in bringing cocaine and weapons into the country; and, therefore were somewhat complicit in the violence and addictions destroying America’s inner cities.

Under Reagan, Black communities of all demographics received the brunt of his federal war, and that war played out on the streets of Chicago like a bad “B” movie.

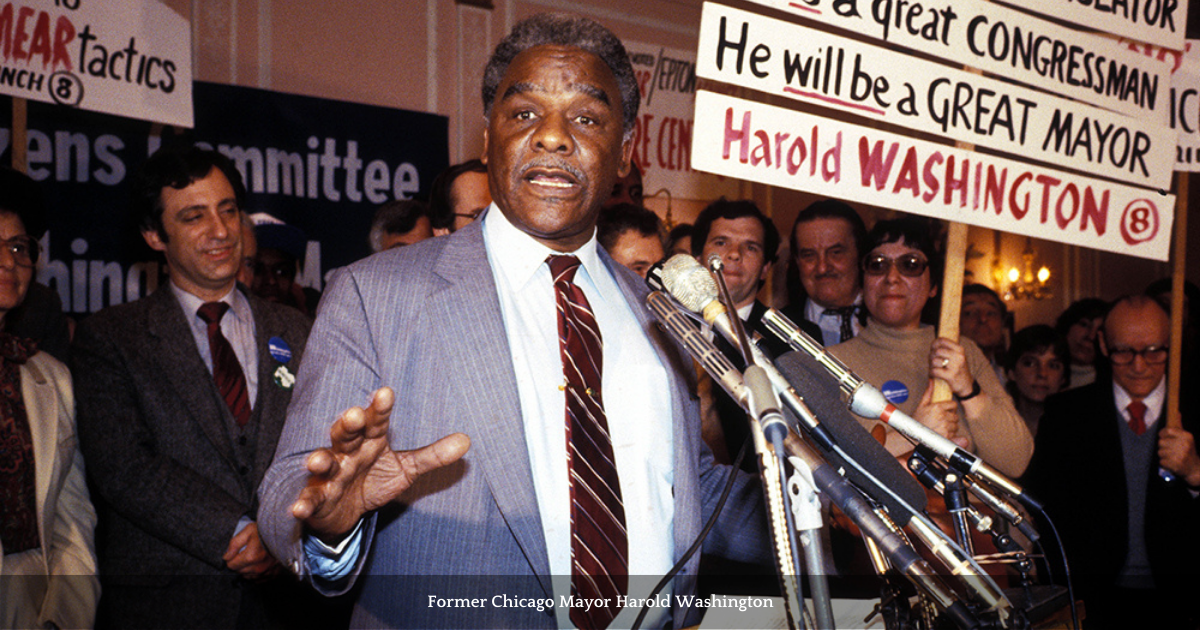

Harold Washington became the hero of Black politics, but then his second pick for police chief set the stage for how Blacks and Latinos would view law enforcement when Leroy Martin said: ‘’When you talk about gangs, I`ve got the toughest gang in town: the Chicago Police Department.”

President George H. Bush was elected, in part due to an effective, racist political ad, that featured career criminal Willie Horton in a dog whistle TV ad that scared white America into calling for even tougher crime policies.

Just as does today’s “The Purge” narrative, designed by Illinois Republicans to circumvent the SAFE-T Act in the midterm election, Bush’s scare tactics conjured the image of Black criminals running the streets on furlough, free to steal, rape and kill.

By the time President Clinton was elected, Chicago found itself in the “grips of gang violence,” and Black men and teens were ignored when saying a rogue cop named Jon Burge was terrorizing and torturing them into false confessions. Clinton’s ’94 federal crime bill created new, harsh criminal sentences and incentivized states to build more prisons and pass truth-in-sentencing laws, all of which was supported by most members of the Congressional Black Caucus.

The ’94 crime bill not only upped the ante on domestic crime policies and led to mass incarceration, it also instituted the death penalty for about 60 more crimes, and encouraged the prosecution of young people as adults—dubbed “super predators.”

Taking a play out of the same old playbook, an 11-year-old homicide victim, Robert “Yummy” Sandifer, who was also a suspected killer, made the cover of Time Magazine albeit through a mugshot.

It is no surprise that by the time George W. Bush was elected in November 1999, that juvenile crime would be a centerpiece of his domestic policy. As a former Texas governor, he took credit for driving down youth crime. By ushering in the personal “Responsibility Era,” a theme that circulated throughout his two-term presidency, Bush worked to stiffen penalties for crimes committed by young offenders.

Soon after the Bush administration dealt with the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attack on U.S. soil, and the debacle of Hurricane Katrina, a number of domestic surveillance and crime policies were enacted to ensure Americans’ safety against an onslaught of criminal immigrants.

“On November 28, 2005, President Bush, speaking in Tucson, conceded that in five years 4.5 million aliens had been caught attempting to break into the U.S. Among the 4.5 million, Bush admitted, were ‘more than 350,000 with criminal records.’ One in every 12 illegal aliens the U.S. Border Patrol had apprehended was a criminal,” according to U.S. authorities.

In 2013, President Barack Obama’s administration finally ended the “War on Drugs.”

As this victory was quietly celebrated by Black America, under Attorney General Eric Holder, local law enforcement agencies were being undergirded. In his first term in office, President Obama increased funding for the Byrne Grant program, which supplied and then increased funding to local law enforcement agencies to run narcotics task forces.

Obama promised a more humane and saner approach to dealing with the nation’s drug and crime problems, but Congress and the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy, complicated and conflated matters. While calling for compassion and understanding of people with addictions, local law enforcement and governance structures continued to wage war on drug users.

Opioids, assault weapons, social and psychological shifts in how people handle conflict and trauma have only compacted economic and quality of life problems in Black communities.

It would appear that no matter how many strides are made toward justice and equity, the system continues to litter the path of progress with legislative landmines.

As criminal justice reform takes center stage in Illinois, Governor JB Prtizker has indicated he would be open to changes in the new law, if not for at least giving the legislation more clarity.

“Well again, I am willing to consider tweaks to the legislation,” Pritzker said in September.

“The legislation is about providing tools and technology to police, making sure we are funding them, and making sure we keep the murderers, rapists, and domestic abusers in jail.”

Reporting made possible by the Inland Foundation.