Photo caption: DR. KING DESCRIBED poverty as “like a monstrous octopus, it projects its nagging, prehensile tentacles in lands and villages all over the world.” The multitrillion dollar poverty-industrial complex ensnares thousands of Chicagoans each year. (Crusader graphic).

Philosopher Aristotle once said, “Poverty is the parent of revolution and crime.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had a more prolific take on the issue. “A second evil which plagues the modern world is that of poverty,” he said during his acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. “Like a monstrous octopus, it projects its nagging, prehensile tentacles in lands and villages all over the world….”

And like a giant octopus lurking just beneath the water’s surface, poverty’s tentacles–violence, homelessness, poor health and nutrition, lack of capital, joblessness, arrests/incarceration, disrupted education, and racial discrimination–have held a tight grip on millions of Americans, tens of thousands who live in Chicago.

Those tentacles can be defined as the poverty industrial complex (PIC). The PIC refers to the web of relationships and incentives between various governmental bodies, nonprofits and private companies that profit from or are engaged in the management of poverty, often without effectively addressing its root causes.

The PIC touches all Chicago neighborhoods and has been especially prolific in communities where predominant Black and Latino people live. Approximately 22 percent of Chicagoans fall below the Federal Poverty Level of $26,200 in annual income for a family of four. Englewood, Woodlawn, West Garfield Park, Washington Park and the Far West Side are areas with the highest concentrations of residents living well below this Federal Poverty Level.

For example, though many South Shore residents are considered well off, 38 percent of residents in the predominantly Black lakefront neighborhood live in poverty, by some accounts. According to a study by the University of Chicago Medicine, the median household income is $26,906 compared to $53,006 citywide. With 21 percent unemployment, it is estimated that 40 percent of households receive food assistance, but nearly 58 percent of residents there suffer from food insecurity.

South Shore was selected for investment under the administration of former Mayor Lori Lightfoot. Before leaving office this past May, she authorized the development of the Thrive Exchange, a $47.3 million mixed-use project that will create 39 residential units on the south side of 79th Street and rehabilitate the historic Ringer Building for commercial use and 24 adjacent condominiums.

This project, in conjunction with the long-anticipated Obama Presidential Center in neighboring Woodlawn, is expected to provide an economic boost to both struggling South Side communities. Hopefuls also believe these investments will go a long way in breaking the psychological hold that entraps so many stuck in the margins, but will they finally break the octopus’ tentacles?

Poverty is created by a unique mix of systemic, situational, and individual factors, such as unemployment, a lack of education, access to nutrition and high-quality health care, addiction, racial discrimination, class, regional, age, or gender bias, misguided public policy, mental and physical disabilities, family dynamics and intergenerational issues, and natural disasters.

In the context of Chicago, many of these factors, including historical racial discrimination, educational disparities, racial hostility, violence, disinvestment, and segregation play a significant role in the higher rates of poverty observed on the South and West side neighborhoods dominated by Blacks.

Local advocates assert that poverty is multifaceted and therefore requires an equally comprehensive, multifaceted approach that considers all these interconnected factors. Different communities may require tailored strategies based on their unique circumstances and challenges. What may work in Englewood may not be applicable in Austin or Woodlawn or South Shore or North Lawndale or Washington Park. However, the social maladies that hamper struggling families living in Altgeld Gardens may be similar to those impacting those who reside in suburban Harvey, Robbins or Maywood.

“Englewood is a dynamic community of working-class people and the extremely poor,” said L. Anton Seals, president of Grow Greater Englewood (GGE), a social enterprise that secured $24 million in federal and private funds to support the development of the Englewood Nature Trail from an abandoned railway corridor. The trail is a 12-foot-wide, ADA-accessible, multi-use path that will run behind 58th and 59th streets between Wallace and Hoyne avenues.

GGE has also focused its efforts on stabilizing legacy homes in danger of foreclosure or demolition due to ill repair. Many adult Englewood residents continue to live in the modest homes of their childhoods, having inherited the properties after the death of parents or grandparents.

About 44 percent of residents of the working-class, blue-collar neighborhood live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census.

“We believe in creating communities that are vibrant, economically secure, self-sufficient and nurturing,” Seals told the Crusader. “When you have all of those factors, there won’t be room for poverty or the conditions that being poor can lead to. Strong neighborhoods are the result of strong intergenerational people who are focused and working together to build and maintain.”

Seals made his comments after hosting an August 19th event for several interns from Englewood STEM High School. The teens participated in a joint program between GGE and Serving People with a Mission (SPM), which teaches leadership skills in youth-driven projects. In addition to backyard farms, where residents grew their own produce, over 36 months, the youth built greenhouses, engaged in neighborhood beautification projects and learned advanced agricultural techniques.

As wasps and butterflies fluttered between flowers and proud family members, SPM graduates staffed vendor booths where they distributed free vegetables and seeds to area residents. The interns told the Crusader the experience made them more determined to finish their education so they can return to Englewood and continue their history of service.

Jae’lon Dyson, 19, who will major in social work at Illinois State University, said, “With each seed planted, I was reminded of the miracles that are before us as a community.

“It’s not just about crops and produce but fostering connections with the land, as well as having a better way of life with the natural resources [we have] at our disposal,” he said.

Erin Nwaehukwu, another graduate of the program, intends to study writing and has enrolled in Amherst College where she will major in English. She recently lost a friend and found healing and hope in the community gardens she helped develop. “I’ve seen the growth in myself and am thankful for the opportunity to develop these skills,” she said.

Despite these snapshots of brilliance, creativity and hope, far too many people in Chicago fall into the gaps. Current Mayor Brandon Johnson and Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, both of whom are Black, have been vocal and strategic in how to dismantle systemic poverty. The mayor is advocating “treatment over trauma” and a solution to homelessness, while Preckwinkle has tackled the county’s health care inequities and developed support for minority- and women-owned businesses.

Former President Barack Obama, who started his political career in Chicago and whose wedding reception was held at the South Shore Cultural Center, once noted, “A child on the South Side of Chicago deserves every bit as much opportunity as a child born elsewhere.” And, yet though he was at the helm of one of the most powerful and richest nations on Earth for eight years, even the first Black president was unable to eradicate poverty and ensure those opportunities reached those in the margins.

“I think President Obama did what he was able to do at the time,” said Keith Harris, a South Side community leader who has shut down construction sites because of a lack of Black workers. “Reality set in that there was only so much he could do. But on the other hand, we had another president, who was the complete opposite on every level, he did whatever he wanted to do and didn’t care what people thought or said about it. Having power and using power are two different things.

“I think [Obama’s] election gave us a serious boost of hope, but it was short lived,” Harris added. “It’s a hard pill to swallow knowing we had a Black president with total power or at least some power, and he doesn’t use it to fully benefit us. That’s why we feel alone and that the federal government isn’t going to solve these issues any time soon—we just have to be proactive [as a people].”

Harris also acknowledged that those who provided services and programs to that sector have grown wealthy. “Poverty is a lucrative business,” he said.

According to Michael Hudson, author of “Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits From Poverty,” the “poverty industry” is made up of “an array of businesses: pawnshops, check-cashing outlets, rent-to-own stores, finance companies, used-car dealers, high-interest mortgage lenders, and trade schools for the poor and uneducated” and services an estimated 60 million consumers in the U.S. Some estimates allege that the poverty-industrial complex earns about $200 billion to $300 billion annually from the low- and no-income population.

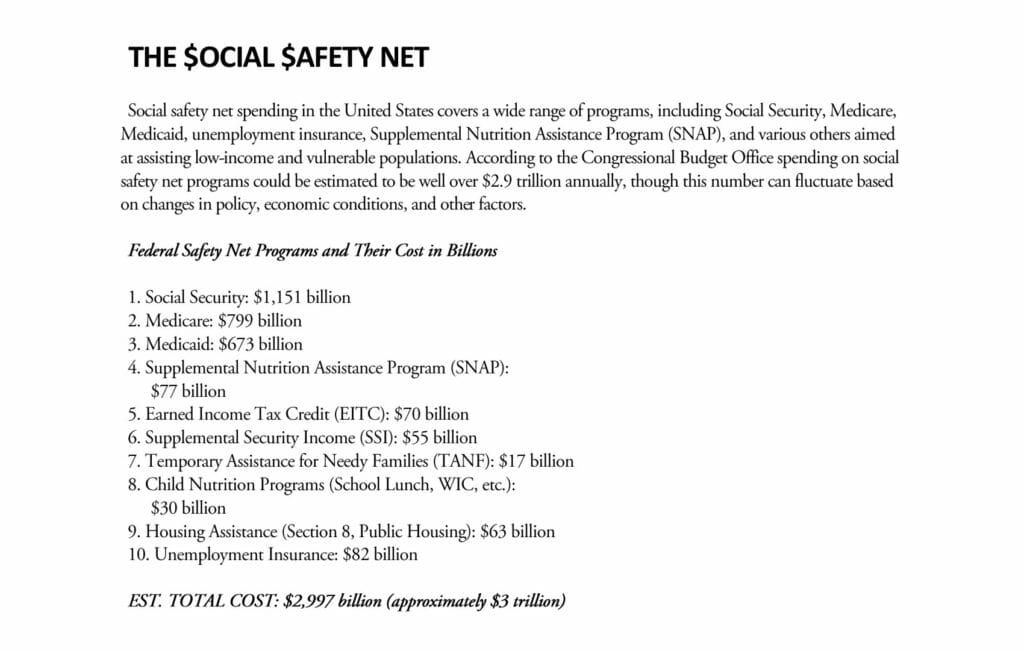

In addition, the federal government spends nearly $3 trillion annually on social safety net programs designed to keep families stable and improve the lives of people experiencing poverty, aging and destitution. (See Crusader Sidebar).

In the U.S., the poverty-industrial complex (PIC) creates a cycle where the needs of the impoverished, including a significant proportion of Blacks, are secondary to the interests of those who profit from providing services or implementing policies. Like the prison industrial complex, critics argue that the poverty industrial complex often perpetuates inequality rather than resolving it.

The creation of federal welfare programs emerged as a crucial response to the confluence of economic hardship and social transformation brought about by the Great Depression and the Great Black Migration. These interconnected events of the early 20th century prompted a paradigm shift in the way the United States approached social welfare, particularly concerning Black Americans who played a significant role in changing laws and pointing out the social contradictions in how they lived versus the vision entrenched in the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution.

The Great Depression’s devastating impact on the economy (1929 to 1939) left millions unemployed and struggling to make ends meet. Concurrently, the Great Black Migration saw a mass movement of Black individuals from the rural South to urban centers in the North, seeking better economic prospects and fleeing racial oppression. Chicago, a hub for Black migrants, became a focal point for these changes.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, enacted in response to the Depression’s upheaval, introduced federal welfare programs that aimed to provide relief, recovery and reform. These programs addressed the dire needs of both the general population and marginalized groups, including Black Americans. The Social Security Act of 1935, a cornerstone of the New Deal, extended its provisions to encompass agricultural and domestic workers, sectors where many Black Americans were employed.

The significance of these programs was particularly pronounced in Chicago’s Black communities, where the convergence of economic hardship and racial discrimination created acute challenges. The Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, part of the Social Security Act, extended a helping hand to single mothers and their families, often benefiting Black households disproportionately affected by joblessness and limited opportunities.

While these original programs have evolved over time, their foundational principles continue to influence contemporary welfare initiatives. Despite the gains secured during the expansive Civil Rights Movement and the corresponding Black Power era, the Black middle class hit a boom and then began to implode, taking with it Black-owned banks, construction companies, insurance agencies, auto dealerships, and medical facilities.

And yet, everyone from U.S. presidents to Black leaders, to sociologists and economists to advocates for the poor, artists and nonprofit leaders, decried the scourge of poverty but collectively seem unable to disrupt or drive it from these lands. “Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor,” noted author James Baldwin.

Some Chicagoans seem divided on whether or not poverty is an inherent, unavoidable social condition as a result of human behavior or if it is a more strategically placed man-made system, the result of human actions, decisions, legislation and social structures also known as capitalism.

Jairus Moore, 30, was born and raised in Chicago’s Englewood community. He grew up on the 6400 block of South Aberdeen where he attended public school and spent his summers visiting grandparents in Memphis. He says he wanted to originally be a police officer but settled on studying electrical engineering after graduating from Hyde Park High School. Now a truck driver for the past five years, he told the Crusader he spends much of his time rehabbing his family’s home and trying to find new ways to provide for himself and his family.

“I think [being poor] comes mostly from individual choice, mostly. Me growing up versus how it is now is totally different,” Moore said. “When I was younger, we had stuff that helped the community. Now kids don’t really have anything to do or anywhere to go. I think people fall into poverty due to a lack of information.

“A lot of people don’t know how to further themselves because they have never been [exposed to that knowledge], but they know how to get a Link Card or child support or government assistance,” he said. “Because that’s where they find immediate information and support. I don’t think anybody chooses to be poor—it’s just the decisions people make that put them on that path.”

Corey Carter, 25, echoed the sentiment. He too grew up on the city’s South Side and has watched his working-class neighborhood become more desolate and full of struggling people. “It seems that every time we make some gains [the government] raises the prices of everything and makes it harder to support your family,” he said. “I believe poverty comes from stuff the government does, but also it can be because of the decisions people make. They can put more jobs out here, but people have to want to work.”

Carter, who is unemployed, stays active with his local youth center. Born and raised in Englewood, he said he has witnessed a decline in values. “I think people are giving up,” he said. “Once you’re labeled as poor, it is hard to shake that off. You’re treated like a charity case rather than a human being. And [the system] makes it harder for people to get off government assistance.

“Even if you get a job making minimum wage or whatever, the cost of living goes up,” Carter said. “It’s like being stuck in a hole and the harder you try to get out, the deeper the hole gets.”

AS ONE OF Chicago’s Black newspapers with a citywide distribution, our mission is to provide readers with factual news and in-depth coverage of its impact in the Black community. This examination is funded in part by a grant from the Inland Foundation and the Chicago Crusader Newspaper.