One day after Congressman Bobby Rush’s historic Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Bill was passed in the U.S. House, Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Tim Scott (R-SC) introduced a similar Bill in the U.S. Senate.

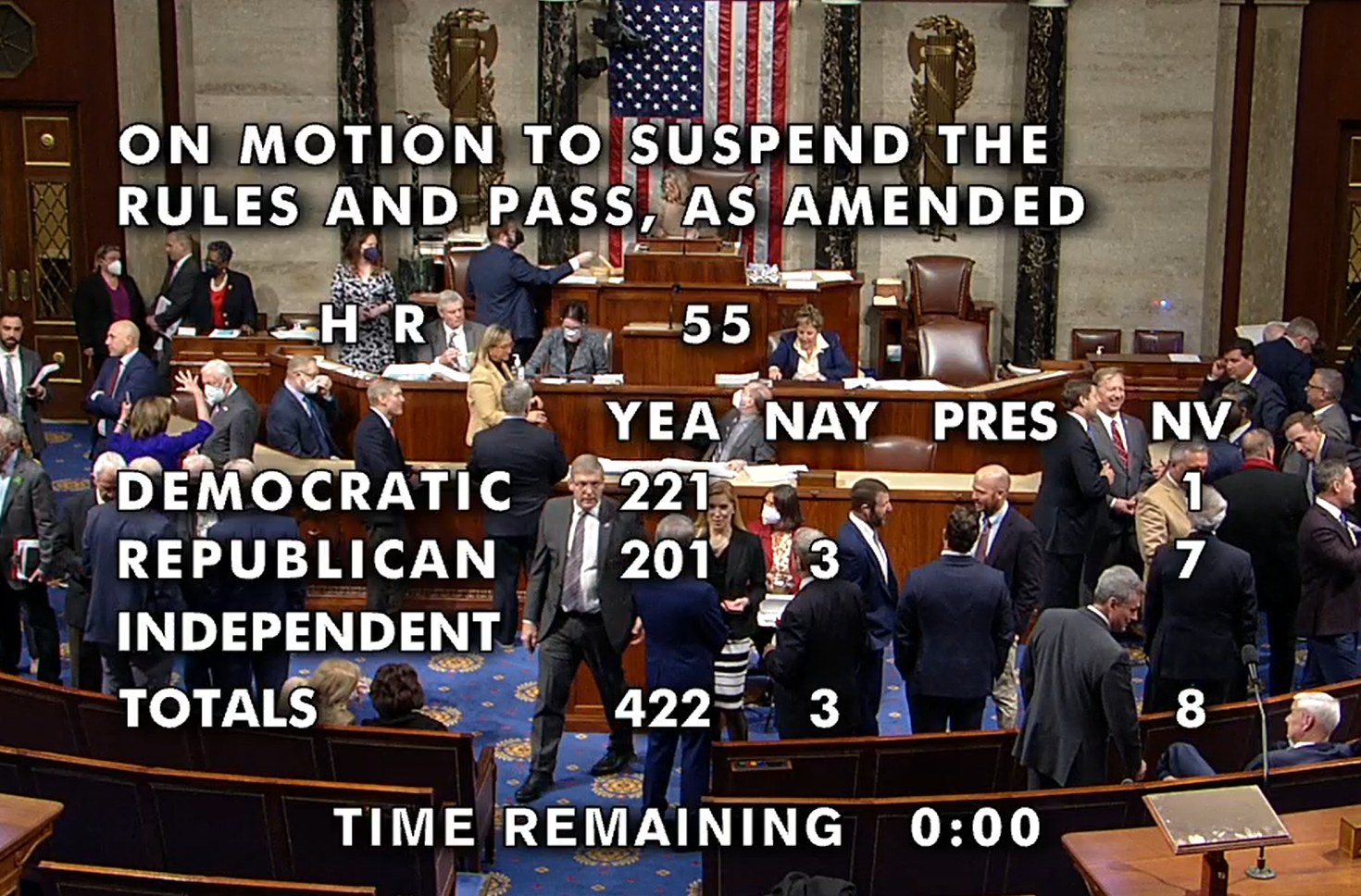

The Bill in the U.S. House was sponsored by Congressman Rush and passed by a 422-3 vote.

“Today is a day of enormous consequence for our nation,” said Representative Rush. “By passing my Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, the House has sent a resounding message that our nation is finally reckoning with one of the darkest and most horrific periods of our history, and that we are morally and legally committed to changing course.”

It’s the 200th time in U.S. history that Black lawmakers in Washington have tried to make lynching a federal hate crime.

More than 6,500 Americans were lynched between 1865 and 1950, according to a report from the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Alabama. A Crusader analysis of EJI data showed Illinois had more lynchings of Black residents than most states in the Midwest.

In recent years, the murders of Black Americans by whites across the country have renewed racial tensions and reshaped a political climate that’s more open to addressing a longstanding problem.

In 2020, the U.S. Senate blocked the anti-lynching bill after it received overwhelming bipartisan support in the U.S. House. Congressman Rush reintroduced the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act on the first day of the 117th Congress.

“The failure of Congress to codify federal anti-lynching legislation — despite more than 200 attempts since 1900 — meant that 99 percent of lynching perpetrators walked free,” Rush said.

“Today, we take a meaningful step toward correcting this historical injustice. I am immensely proud of this legislation, which will ensure that the full force of the U.S. Federal Government will always be brought to bear against those who commit monstrous acts of hatred.”

Under the Bill a crime can be prosecuted as a lynching when a conspiracy to commit a hate crime results in death or serious bodily injury. The legislation passed by the House today differs from the anti-lynching legislation passed during the 116th Congress in two primary ways:

The maximum sentence for a perpetrator convicted under the Anti-Lynching Act is 30 years; the previous version of the legislation set the maximum sentence at 10 years. These charges would be in addition to any other federal criminal charges the perpetrators may face.

The legislation applies to a broader range of circumstances. Under the legislation passed last Congress, a crime could only be prosecuted as a lynching under very specific circumstances, such as if it took place while the victim was engaging in a federally protected activity.

The bill is named after Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black teenager from Chicago who was brutally murdered by two white men in Money, Mississippi, in 1955. His mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, held an open casket funeral in Chicago to show the world what the men had done to her son. No one was ever brought to justice.

Rush said, “I was eight years old when my mother put the photograph of Emmett Till’s brutalized body that ran in Jet Magazine on our living room coffee table, pointed to it, and said, ‘this is why I brought my boys out of Albany, Georgia.’

“That photograph shaped my consciousness as a Black man in America, changed the course of my life, and changed our nation. But modern-day lynchings like the murder of Ahmaud Arbery make abundantly clear that the racist hatred and terror that fueled the lynching of Emmett Till are far too prevalent in America to this day.”

After the Bill passed in the U.S. House, Senators Booker and Scott introduced a similar Bill in the Senate.

“Between 1936 and 1938, the national headquarters of the NAACP hung a flag with the words ‘A man was lynched yesterday,’ a solemn reminder of the reality Black Americans experienced daily during some of the darkest chapters of America’s history,” said Senator Booker.

“Used by white supremacists to oppress and subjugate Black communities, lynching is a form of racialized violence that has permeated much of our nation’s past and must now be reckoned with.

“To that end, I am proud to introduce this legislation to help us acknowledge the pain caused by lynchings and make the shameful practice a federal crime. Although this Bill will not undo the terror and fear of the past, it’s a necessary step that our nation must take to move forward.”

Senator Scott agreed.

“While we cannot erase our nation’s past, we can work toward a better future for all Americans,” said Scott.

“The Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act will do just that. This long-overdue piece of legislation sends a clear message: We will not tolerate hatred and violence against our fellow Americans.”