Over 4,000 emergency calls to Chicago police were made by residents in South Shore and Woodlawn, who waited more than an hour for help, according to 2022 data released by the city in response to a legal settlement.

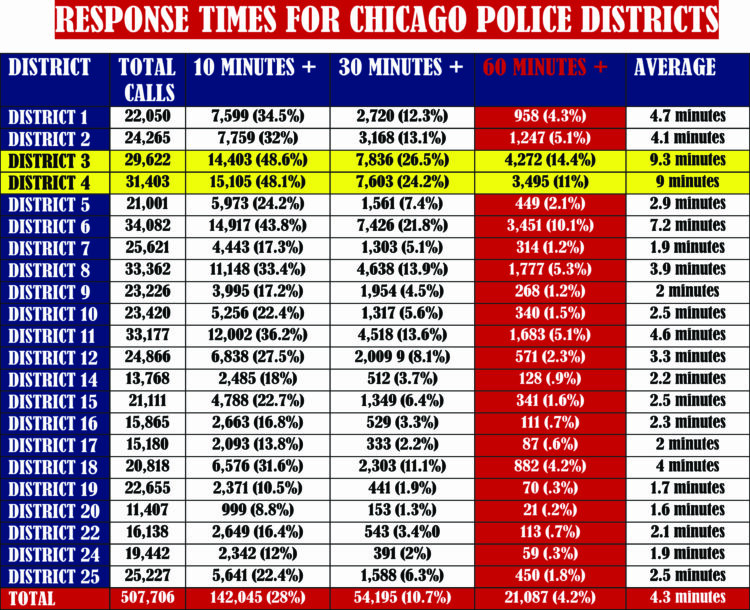

The data gave response times of Chicago’s 22 police districts throughout the city. The data listed 507,706 in three separate categories.

About 142,045, or 28 percent of the calls took more than 10 minutes. About 54,195 calls or 10.7 percent took more than 30 minutes. About 21,087 or 4.2 percent of emergency calls to police took more than an hour.

Most police districts on the North Side had response times that were under three minutes. However, data show the response times were higher in police districts in less affluent neighborhoods on the South Side.

The 20th Police District, which includes Lincoln Square, Edgewater and a slice of Uptown, had the shortest police response times where it took an average of 1.6 minutes for police to respond to 911 calls.

The data also show that only 21 out of 11,407 calls in the 20th District took an hour for police to arrive at the scene.

On the South Side, data show the 3rd Police District had the longest response times than any district, in all three categories. The district serves Greater Grand Crossing, Woodlawn and South Shore.

According to the data, of 29,622 emergency calls to that district, 48.6 percent of the calls took more than 10 minutes, while 26.5 percent of the calls took more than 30 minutes. About 4, 272 calls (14.4 percent) took more than an hour for police to arrive.

One highly publicized incident in District 3’s South Shore that highlighted the response time problem occurred at the Jeffery Pub in the early morning hours of August 14. Tavis Dunbar, 34, was charged with murder after killing three men whom he hit as he drove southbound on Jeffery Boulevard after a brawl outside the club. Another man survived his injuries.

Data show someone called the police at 4:30 a.m. after a fight spilled out into the street. At 4:58, the crash occurred, about 27 minutes after the first 911 call about the earlier assault. At 5:35 a.m., a police officer arrived at Jeffery Pub, 64 minutes after the initial 911 call.

In the 4th Police District, which includes parts of South Shore, Avalon Park, South Chicago, Calumet Heights, Burnside, East Side, South Deering and Hegewisch, there were a total of 31,403 emergency calls. Of this number, 15,105 (48.1 percent) took at least 10 minutes before police responded, while 7,603 (24.2 percent) calls were responded to in 30 minutes or more. A total of 3,495 (11 percent) calls took more than an hour for police to arrive.

The 6th Police District had the third worst response time in the city. The district serves parts of Greater Grand Crossing, Auburn Gresham and Chatham.

Data show that the 6th District had the most 911 calls in the city with 34,082 calls. About 14,917 (43.8 percent) took police at least 10 minutes to respond, while 7,426 (21.8 percent) took more than 30 minutes for an officer to arrive. A total of 3,451 (10.1 percent) calls took the police more than an hour to respond.

The data was first reported by the Chicago Tribune, which did not respond to detailed questions about the newspaper’s findings, including possible reasons for delayed responses and why some dispatch times for high-priority calls exceeded 60 minutes. The department issued a brief statement, saying it was “committed to timely response to calls for service within every neighborhood citywide.”

The data doesn’t include all high-priority calls and a third of the calls the department didn’t document when officers arrived at the scene. The police department also said some arrival times that were logged may be inaccurate.

In essence, the charts measure the travel time for officers, excluding the time it took for a 911 operator to pick up the phone, to discern the nature of the call and to hand the call off to a dispatcher, as well as the time that elapsed before the dispatcher directed an officer to the scene.

The charts also come with a big caveat: The data they are based on doesn’t include all high-priority calls. In a third of those calls, the Department didn’t track when officers arrived at the scene, so those calls were excluded from the Department’s calculations. The Department also warned that some of the arrival times logged may be inaccurate. But the Department’s record keeping was reportedly spottier for lower-priority calls, such as parking violations.

The data was released after residents of Austin and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a federal Civil Rights lawsuit against the city a decade ago, demanding to know whether police response times in the city were slower in Black communities. The lawsuit also noted that the neighborhoods that suffered from high violence rates also suffered long police response times.

In a statement, the ACLU said, “an unfair deployment scheme results in longer delays and even denials of responses to critical 911 calls in minority neighborhoods as compared to white neighborhoods.”

In that settlement, the city acknowledged that “people in predominantly minority neighborhoods should not wait materially longer for responses to 911 calls than people in predominantly white neighborhoods.”