Photo caption: MANY KNOW THE historic Wabash YMCA in Bronzeville as the birthplace of Black History Month but, in its heyday, Olympian Jesse Owens, Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and retail merchant Marshall Field III were among notable guests at the facility that was also the birthplace of the Chicago Urban League and the NNPA, a national organization known as the Black Press.

Robert S. Abbott was dying. In his mansion on South Parkway (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive), the founder of the Chicago Defender was on his deathbed while his nephew John H. H. Sengstacke was speaking less than two miles away at the Wabash Avenue YMCA at 3763 S. Wabash. While Sengstacke was giving his opening remarks to a group of Black publishers from across the country, Abbott drew his final breath.

That cold day in February saw one chapter in the history of Black Chicago close, and a new chapter begin. Abbott was gone, as nearly 200 Black publishers banded together to establish the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), today the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA).

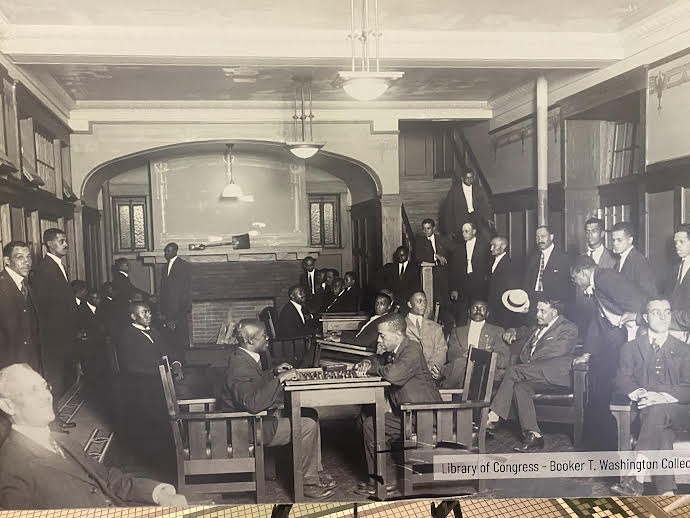

The meeting was a historic one as Bronzeville’s Black Belt welcomed tens of thousands of Blacks from the South during the Great Migration. Amid restrictive covenants among white property owners, housing and employment were growing problems in Chicago. Blacks, regardless of their socioeconomic status, weren’t allowed to stay in hotels in Chicago and were shut out of segregated white private clubs.

Sengstacke’s historic publishers’ meeting was another defining moment in the storied history of the Wabash Avenue YMCA.

At a time when Chicago’s mainstream newspapers shunned stories on Black residents, Black newspapers published stories that became the first draft of Black history.

Many people across the country know that Chicago’s iconic Wabash Avenue YMCA was the birthplace of Black History Month, yet few Blacks know the historic site is also the birthplace of several Black storied institutions.

When media outlets and newspapers mention the Wabash Avenue YMCA, they simply mention it as the birthplace of Black History Month. While there are plenty of articles and books on the historic month, there are none written about the Wabash Avenue YMCA, an iconic Black institution with a rich history that includes the establishment of the foundations of prominent Black institutions.

Untold are the stories of the Wabash Avenue YMCA, whose decades of existence included visits by prominent Blacks and rich businessmen, including Olympian Jesse Owens, aviator Bessie Coleman, Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and retailer Marshall Field III, grandson of the founder of Chicago’s legendary, now defunct, department store.

For more than a century, the Wabash Avenue YMCA stood in Bronzeville, weathering years of financial problems while offering programs that helped Blacks in Chicago survive segregation, poverty and housing and employment discrimination.

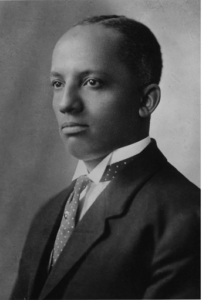

The facility’s biggest legacy is its recognition as being the birthplace of Black History Month. It happened decades after Carter G. Woodson visited the Wabash Avenue YMCA in 1926 and established Negro History Week.

However, not many Blacks know that 10 years earlier, the Chicago Urban League, in 1916, was founded at the Wabash Avenue YMCA according to the book, History of the Chicago Urban League by Arvarh E. Strickland.

In 1915, four years after the founding of the National Urban League in New York City, the organization began efforts to extend its work into Chicago. At the time, Chicago had the second largest population in America.

Like New York, Chicago had a growing Black population where finding jobs and housing were a challenge, as Blacks moved into the city during the Great Migration. These conditions led Urban League officials to believe their programs would succeed in Chicago.

In November of 1915, Eugene Kinckle Jones, associate director of the National Urban League, visited Chicago. He met with a small group of white and Black leaders at the City Club in the Loop. Supportive white officials from the University of Chicago joined the movement in subsequent meetings.

Chicago’s Black leaders at the time were concerned that an Urban League branch would compete against other Black institutions for influence and philanthropic support.

But George Cleveland Hall, the chief surgeon at the predominately Black Provident Hospital, was one of the first Black leaders to actively support the creation of the Chicago Urban League. Hall is one of four founding members of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which in turn founded Negro History Week.

A friend of pioneer Booker T. Washington, Hall won the support of philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, who among his causes in the Black community donated $25,000 to the construction of the Wabash Avenue YMCA.

Another supporter who backed the creation of the Chicago Urban League was Abbott, who publicized the National Urban League’s visit and efforts in his editorial pages.

It took a long 12 months to set up the organization. But on December 11, 1916, the first meeting was held at the Wabash Avenue YMCA. Among those present were Hall, Jones, T. Arnold Hill, the Urban League’s national organizer, and numerous leaders of Chicago institutions.

The executive board held its first meeting weeks later on January 10, 1917.

According to Strickland’s book, it was Rosenwald’s financial assistance that enabled the Chicago Urban League to pay its bills in its first year. In March 1918, with the urging of social reformer Celia Parker Woolley, the Chicago Urban League moved out of the Wabash Avenue YMCA and relocated to her Frederick Douglass Center at 3032 S. Wabash Ave.

By 1924, a total of 28,000 members occupied more than 160 Black Y’s throughout America, according to the YMCA Metro of Chicago. During the YMCA’s 53rd Anniversary Dinner, Booker T. Washington said, “This YMCA building branch for our people will come further, in my opinion, in helping the Negro young man in finding himself, to articulate himself, in its civilization, than any other movement that has been started in the city of Chicago.”

The Chicago Urban League was the National Urban League’s first branch outside of New York City. It became one of the most successful branches in the country and at one point was considered more powerful than the National Urban League in New York City.

Fast forward to 1940. John Sengstacke was being groomed as the future publisher of the Chicago Defender, while Abbott remained confined to his mansion as his health declined from Bright’s disease.

By that time, the Defender moved its operations from a State Street apartment owned by a widow, Henrietta Lee, to its new headquarters at 35th and Indiana Avenue.

Abbott had long had a dream of bringing together the nation’s Black publishers but his health was failing. Sengstacke picked up the baton and organized the first ever conference of Black newspaper publishers at the Wabash YMCA. It was held during a leap year on the morning of February 29, 1940.

Abbott’s rival Robert Vann, owner and publisher of the Pittsburgh Courier, did not attend, but sent a reporter to cover the meeting, according to Ethan Michaeli, author of The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America.

According to Michaeli, Sengstacke aimed to smooth relations between the Black publishers in the competitive newspaper industry.

During his welcoming remarks the group learned that Abbott had died in his sleep that morning. The group adjourned the meeting for several hours, reconvening with a renewed purpose to carry on Abbott’s legacy.

At the meeting, the group decided on a name for the new organization. They named it the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA). In later years the name would be changed to the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA). Today, the NNPA is headquartered in Washington, D.C.

Two years after its initial meeting, the NNPA had its third annual convention at the Wabash Avenue YMCA, according to Time Magazine. Noted the magazine, one of the speakers at the convention was Marshall Field III, who founded the Chicago Sun-Times newspaper.

Field, whose namesake department store prohibited Blacks from trying on clothes in its fitting rooms, urged the Black Press to “go easy on the race issue.” Black publishers found the advice interesting, since Field owned a Black newspaper in New York’s Harlem neighborhood called The People’s Voice.

More than half a century later, in 2005, the NNPA returned to the Wabash Avenue YMCA to mark the 65th anniversary of the organization’s founding.

According to Tara Balcerzak, a researcher for the Renaissance Collaborative, other groups that have met at the Wabash Avenue YMCA include the National Negro Insurance Association, National Alliance of Postal Employees, Association of Science Teachers in Negro Colleges (now the National Institute of Science), the Chicago Music Association, the National Airmen Association of America and the National Aviation Committee, of which Aviator Bessie Coleman was a member.

In addition to Coleman, four-time Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens visited the Wabash Avenue YMCA. In 1956 famed dermatologist T.K. Lawless, who operated a nationally known clinic on Martin Luther King Drive (at the time South Parkway), was honored at the Wabash Avenue YMCA for his financial contributions to Black youth.

In 1960, Owens visited the facility to kick off a $5,000 fundraising campaign. That same year, baseball legend Jackie Robinson visited the facility before he spoke to 500 people at the Sheraton Hotel, where he blasted Civil Rights leaders who urged weary Blacks to be patient in gaining racial and economic equality.

Globally-renowned Black cyclist Marshall “Major” Taylor, believed to be the fastest cyclist in the world, practiced at the Wabash Avenue YMCA. Born in 1878 in Indiana, Taylor was the first Black cyclist ever to win a world championship. He traveled the world and broke records, despite efforts to ban him from competing because he was Black. Illness and financial woes left him nearly destitute, as he lived out his final years at the Wabash Avenue YMCA until his death at 53 in 1932. A campaign is underway to honor him posthumously with a U.S. postage stamp and a Congressional Gold Medal.

The Chicago Crusader also has longstanding ties to the Wabash Avenue YMCA. The Crusader’s co-founder Joseph Jefferson was an employee at the Wabash Avenue YMCA, where he taught swimming and helped organize the Negro Labor Relations League, an organization that fought for Black workers, who were shunned by white labor unions.

Jefferson, along with Crusader Founder Balm L. Leavell, mounted a campaign against dairy companies that wouldn’t promote Blacks or allow them to drive milk delivery trucks.

The two activists urged the Chicago Defender to publish stories on the plight of Black workers. Unhappy with the lack of coverage in the Defender, five months after the historic founding of the NNPA at the Wabash YMCA, Jefferson and Leavell in June, 1940, started a newsletter called The New Crusader. Decades later, the newsletter would become a Black weekly newspaper renamed The Chicago Crusader.

In its heyday, the Wabash Avenue YMCA was host to society balls, national conferences, fashion shows, Easter festivals, fundraisers, concerts, political rallies, athletic competitions and sports championship events. But amid the festivities, there were some difficult times, too. Numerous fundraisers over decades were held as the facility’s finances grew bleak.

And there were other public relations problems. In 1935, a 14-year-old girl drowned during a swimming class in the facility’s pool, according to an article in the Chicago Defender. In 1937, a youth attempted to take his life there, by consuming iodine. He was taken to Provident Hospital where he was treated and released. The iconic venue also faced the spectre of competition.

On July 1, 1951, the Washington Park YMCA opened at 50th and Indiana Avenue. The facilities offered were even grander than those at Wabash. The five-story structure featured luxurious lounges for both men and women, a cafeteria, private dining rooms and a large banquet room that could seat 300 guests. It also had 278 air-conditioned dormitory rooms and single, double and multiple units for married couples. In 2003, the 52-year-old Washington Park YMCA closed as part of the YMCA Metro of Chicago’s cost-cutting plan.

During the 1960s, many Black YMCAs became meeting places and rallying points for the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Reverend Andrew Young often swam at local YMCAs with their families while home, momentarily away from obligations to the freedom movement.

Black leaders Vernon Jordan, former Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson, Dr. King and Congressman John Lewis all grew up at the historic Butler Street YMCA in Atlanta, while Andrew Young spent his grade-school days in the Dryades YMCA in New Orleans. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall grew up at the Druid Hill YMCA in Baltimore, according to the YMCA Metro of Chicago.

But the Wabash Avenue YMCA in Chicago is perhaps the most revered among the Black Y’s because of its contributions to the founding of Black History Month.

In 1981, after years of decline and mounting financial debts, the facility closed and was boarded up. St. Thomas Episcopal Church bought the facility for $1 but later learned that pipes and other items were removed before the building was sold. During the 1980s and 90s, the building fell into disrepair; and a demolition permit was issued to tear it down. In 1986, the building was designated a Chicago Landmark. That same year it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the late 1990s, St. Thomas, Quinn Chapel AME Church, Apostolic Faith Church and St. Elizabeth Church formed the Renaissance Collaborative to facilitate a $10.4 million renovation of the facility in 1998, before it reopened in 2001. During the renovation, Artist William E. Scott’s massive mural that he painted in the ballroom in 1936, was restored decades after it was painted over.

During that renovation, Patricia Abrams, president of the Renaissance Collective, told the Crusader that the process was a journey that included people who frequented the Wabash Avenue YMCA when they were growing up.

“I wanted to know how people felt about the building,” Abrams told the Crusader.

In 2015, the Wabash YMCA closed a final time; it has been shuttered ever since.

The Renaissance Collaborative, now an independent, non-profit organization has launched another renovation effort to get the facility back open.

On February 4, 2023, a Crusader journalist viewed the facility during a tour of the venue. Most of the living and public areas remain in good shape. Abrams said the Collective received a $346,000 grant, but the facility’s swimming pool will cost an additional $246,000 to renovate after workers said the entire area needs to be rehabbed.

“America is a wasteland in terms of history. We don’t appreciate our history, especially Black History,” said Dr. Lionel Kimble Jr., associate professor of History and Africana Studies at Chicago State University.

After graduate school at the University of Iowa, Kimble started researching the history of the Wabash YMCA. He became a member of the Association for the Study of Life of African American History.

Kimble taught for 17 years at Chicago State. He teaches a two-part African American history course that includes a tour of the Wabash Avenue YMCA.

“I hear students don’t like Black history because it’s a painful history,” Kimble said. “But if we don’t look at the history of the Wabash YMCA, we won’t realize how positive Black history can be.”