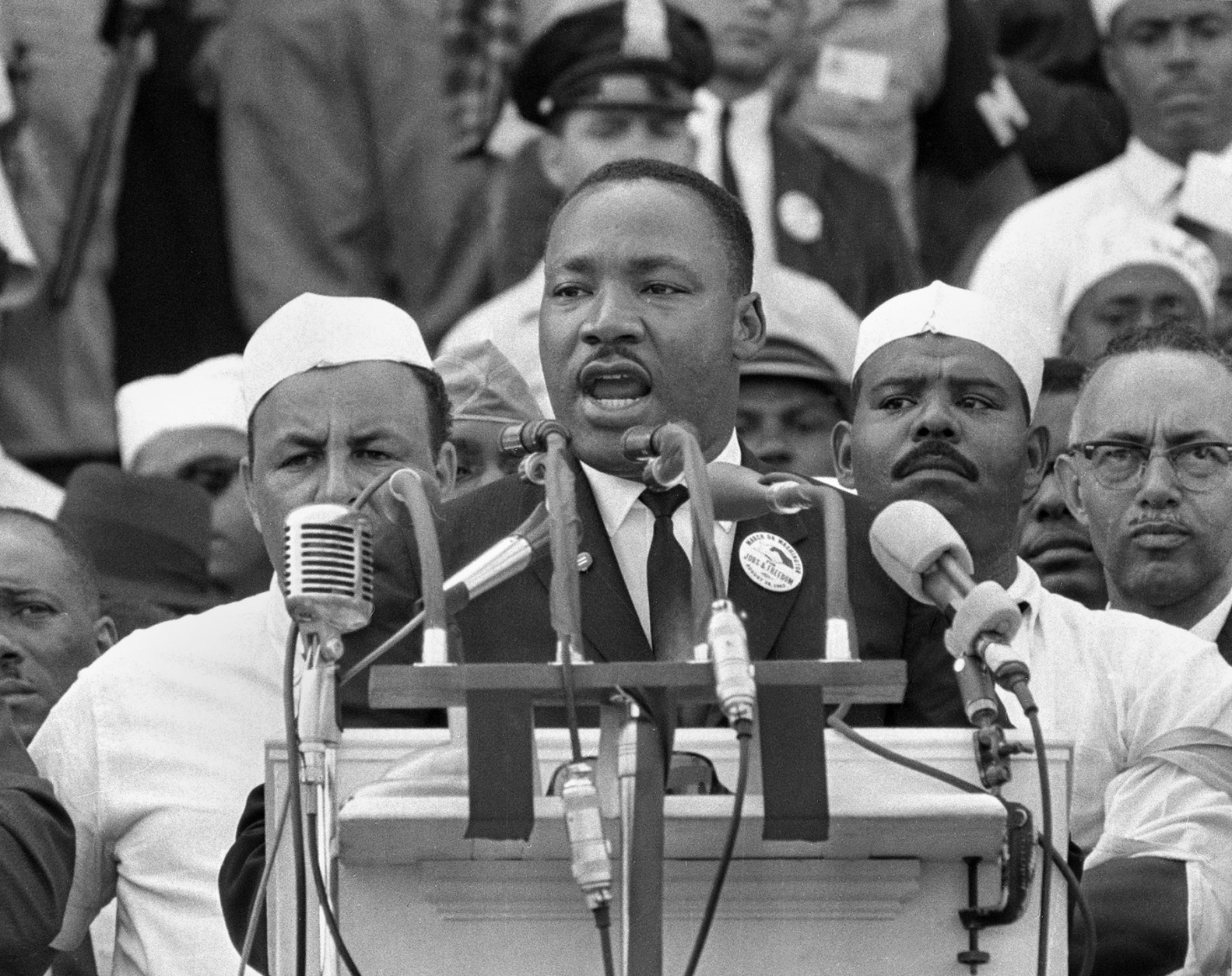

Fifty-nine years ago, a security guard who didn’t plan on attending the historic March on Washington ended up standing next to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as he gave his historic “I Have a Dream Speech.” Seventeen minutes later the speech was over, and the crowd exploded with applause.

George Raveling, a basketball star who guarded King at the Lincoln Memorial asked him for a copy of his speech. It was a request that Raveling would never forget as he became the owner of a priceless document that led King to make an impromptu speech that moved millions during one of the most significant events in Black history.

It may be worth millions, but today, that same copy of King’s original “I Have a Dream” speech is on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D. C. Since January 13, the document has been encased in a glass display in the “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom” gallery. After marking last month’s King Holiday, the document will remain on view throughout Black History Month until February 27.

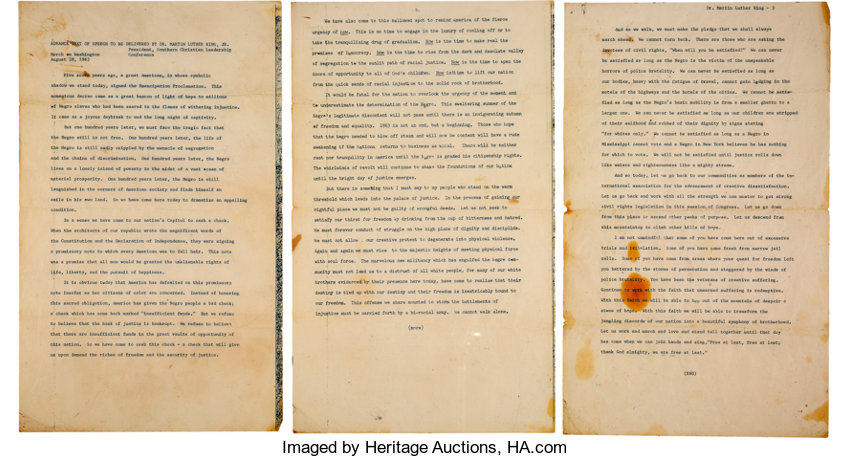

It’s a document of a speech that ranks among the greatest in American history. It is three pages and 1,470-words.

Approximately 250,000 people heard King’s speech as he stood on the steps of the iconic Lincoln Memorial. But visitors to the museum won’t see the key part in the speech that electrified Blacks across the nation and boosted King’s profile as the eloquent Pied Piper of the Civil Rights Movement.

King was gaining momentum at the beginning of his speech when gospel singer Mahalia Jackson repeatedly said “Tell them about the dream,” as she sat behind King.

King then began, delivering his famous words, “I have a Dream.” He went off script, spoke from his heart, and turned a speech into an oratorical masterpiece. To millions, the speech made King their King.

On the 100th Anniversary of Lincoln’s Emancipation, King’s speech fired up a movement that galvanized Blacks across the South and the nation.

Today, the eloquent words of King’s famous speech are still powerful and the vivid symbolism that articulates his message of equality and freedom still resonates with many people.

For King, the speech will forever be tied to his legacy and contribution to Black history. Children in schools across the country recite the speech. Radio stations everywhere play the recording during the King Holiday in January.

King had originally prepared a short and formal speech about the sufferings of African Americans attempting to realize their freedom in a society chained by discrimination. Officially, the March on Washington is known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. But these issues became part of a bigger vision as King spoke of his dream.

The King family in Atlanta still owns the intellectual rights to their father’s recorded speech on August 28, 1963. Anyone wishing to use it for commercial purposes must pay a fee.

While the original copy does not contain the most famous part of King’s speech, visitors to the NMAAHC can appreciate the historic document in its original form. They will also notice that the document does not have any of King’s markings on it.

About 300 copies of the speech were reportedly given to members of the media before King spoke. They have a handwritten copyright symbol that organizers added before they were distributed. Raveling’s copy does not have one, suggesting it’s not a media copy and more likely to have been King’s.

On February 20, 2020, one copy was sold for an undisclosed amount by Heritage Auctions, a large auction house that sells thousands of historical artifacts tied to American History.

One copy of King’s speech reportedly is in the archives of the King Center for Non-Violent Change in Atlanta.

For more than 50 years, Raveling kept his copy in a bank vault in Los Angeles. Last year, he donated it to Villanova University, where he served as the school’s basketball coach before working in similar positions at the University of Southern California, Washington State and the University of Iowa. Villanova loaned the copy to the NMAAHC.

How Raveling obtained the original copy of King’s speech is a story itself. Days before the March, Raveling was visiting a friend’s father in Claymont, Delaware, nearly two hours north of Washington. The night before the March, Raveling and his friend were asked by an organizer if they could volunteer to serve as security guards. They agreed and the next morning they were given credentials and white caps.

King was the 10th speaker on the program. After he finished his speech with the words “Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” King pivoted left on the podium and took his papers off the lectern in his right hand.

That’s when Raveling, then 26, reportedly asked him for a copy of his speech.

King gave Raveling a copy and was about to say something to him when a Rabbi came up to congratulate the civil rights leader. Raveling then put the copy of the speech inside an autographed copy of a memoir by President Harry Truman, whom he met in a trip to Missouri for an all-star basketball game. Reports say Raveling put King’s speech in the book because he knew that he wouldn’t lose or throw away a book that’s signed by a U.S. president.

A scholar who once examined Raveling’s copy confirmed that it was the real thing.

In 2013, USA Today reported that Kenneth Rendell, an expert on rare documents, estimated that Raveling’s copy could sell for $20 to $24 million because he obtained it during the “high point of the civil rights movement.”

In that same article, Raveling said he was offered $3.5 million but had “no intention of selling it, because I don’t believe it’s my property. I’m just the guardian. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time.”