By Shayla Simmons

Nestled within 11 blocks of South Michigan Avenue, the foundation of music as it is known today found its roots in the form of a series of independent record labels focused on Black music for Black audiences, known as Record Row. Preceding even the hits of Motown, the artists of Record Row, and the labels that created them, began the foray into the music industry, changing the trajectory of music forever in the two decades, from the 50s to the mid-70s, that the small community hailed as its heyday.

Growing from the ground up, labels sporting names as colorful as the talent they housed, such as One-der-ful, Chance, King, and OKeh, called Record Row home and comprised the soundscape for the Black experience and blueprint for modern music.

Southern transplants were enticed by the city’s economic opportunities presented by the north in the form of factories and steel mills and supposed freedom from oppression, known as the First Great Migration. Presented for the first time with disposable time and income, this new class itched for entertainment, which came in the form of club life and amateur musical talent.

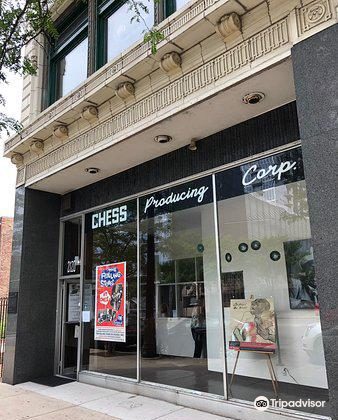

One such nightclub was the Macomba Lounge, which was a Black’s only nightclub owned by Polish immigrants and brothers, Leonard and Phil Chess. Together they recognized the value in recording the live music that filled the club, ultimately deciding to close shop to start a new venture in 1950 – Chess Records, one of the leading labels on Record Row.

The label was built on the backs of unskilled laborers turned stars, such as the case of McKinley Morganfield, a Mississippi transplant and truck driver who became known as Blues legend Muddy Waters. Eventually, they grew to create additional stars such as Bo Diddley, the Four Tops, Minnie Riperton, and Etta James.

Leonard Chess continued to innovate the music landscape, purchasing the first radio station in the city that exclusively played Black music, WVON. While there was a personal gain in the form of commercials and boosted record sales, the station became the heartbeat of Black music across the United States.

“Because it was the powerhouse Black station in Chicago, that made it one of the powerhouse Black stations in America, and thus a trendsetter. If you could break a record or get a record happening in Chicago, it served as a precedent for getting it happening in New York, or L.A., or Detroit,” explained music television personality, Don Cornelius, in ‘Cradle of Soul.’

Only six blocks down the strip was Vee-Jay Records, an acronym of sorts representing the initials of Vivian Carter and Jimmy Bracken, a husband-and-wife duo that used a $500 loan to start up one of the first Black-owned and operated labels in the country. Together with the help of Vivian’s brother, Calvin Carter, and Ewart Abner (who eventually became label president),

Vee-Jay produced stars from across genres, even becoming the first American label to sign the Beatles.

While all were vying for their own successes, as a whole, the musical product produced by all the labels was celebrated far and wide.

“There was a synergy between the labels,” explained Glenn Cosby, former V103 radio personality and Record Row expert. “There was solidarity. They helped one another out just as much as they competed against one another.”

Yet the star power and the genre-defining productions that have become hallmarks of the musical label conglomerate only represent a portion of Record Row’s cultural significance and continued legacy.

The Black music and entertainment industry Record Row forcibly carved into society was heavily ingrained in moments of Black innovation and produced opportunities of social mobility that were virtually impossible for Black people to experience before the creation of Record Row.

On the most foundational level, Record Row was the perfect soil to build a booming local economy around the necessities needed to sustain the level of growth seen on Michigan Avenue.

“With the creation of Record Row came many new opportunities for Black professionals. Black professional musicians, accountants, businessmen, entrepreneurs,” said Portia Maultsby, ethnomusicologist and historian. “Record Row provided role models. I’m sure no one saw it that way at the time, but it did send the signal that Black entrepreneurship can work.”

The ambition to not only thrive but to prosper is what produced Black entrepreneurs like Ernie and George Leaner. Nephews of famed disk jockey Al Benson (the first to play blues music on the radio), founded United Record Distributors – the first and only Black and independent record distributor in the country.

Their business exalted Black professionalism, creating opportunities for economic advancement where there was little opportunity before. By hiring Black personnel to ship to Black deejays who played Black music, a precedent unlike any other was established, prompting other groups to prioritize hiring Black staffers.

“During that time, they, along with the other artists on Record Row, were instrumental with getting these artists out there and recognized for their talent. And I’m just very blessed that our family was a part of that,” said Phyllis Leaner, daughter of Ernie Leaner, when asked about her family’s legacy in the business.

Moreover, overcoming the color barrier, against a world so opposed to its very existence, Record Row was a beacon for Black power, creativity, longevity, and ground zero for the Black revolution.

For much of Record Row’s lifetime, the very product that sustained the community was ill-received by anyone other than the Black community, rampant racism and segregation finding its hold even in the music. The success of the most popular Black artists paled in comparison to white artists that stole the sound born on Michigan Avenue.

“Usually when people are not affected by an injury, they have a tendency to think in terms of the injury not being so great. The Spaniels, for instance, recorded a song called ‘Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight’, [selling] a half a million copies basically in the Black community. The McGuire Sisters recorded the same song, [selling] two or three million copies. It’s about money. And when you are denied access to a market, based on the color of your skin, that becomes personal. It no longer becomes much to do about nothing,” said singer-songwriter Jerry Butler, once the front man of the Impressions, encapsulating the frustration.

Even still, the music persevered. In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, artists used their platform to create battle cries that spurred on the movement, and DJs used the airwaves to keep the community informed. Both the music and the industry became political in the face of injustice and in the fight for freedom.

Despite creating legends, Record Row saw its end for the very reason it was conceived. By the 1970s, Black music had become fully ingrained in the popular culture of the country, and with that, in demand by the very labels that barred them access. Mainstream record labels began to poach artists and their master tapes at a rate the independent labels could not compete with.

Today, the legacy of Record Row is nearly lost to the annals of time, save for those who refuse to let history remain history. While most of the major players that laid the foundation for the Chicago sound have since passed, their memories live forever in the form of the records they left behind.

“A record, it’s your footprint in time. It’s your footprint in sand…It’s a piece of a guy or a girl’s life,” described the late Ewart Abner, one-time record executive of Vee-Jay Records. “That’s their best effort. And we were able to put it out there, make it available to those who wanted it. That’s a good feeling.”

Links to Black History Special Edition 2022 Stories & Timeline:

Barbara Acklin, Chicago’s Empress of Soul

Dynamic Duo: The Leaner Brothers

Timeline: A Brief History of Chicago Soul–Hit Records and Black Owned Record Labels