By Bryan Marquard, Boston Globe

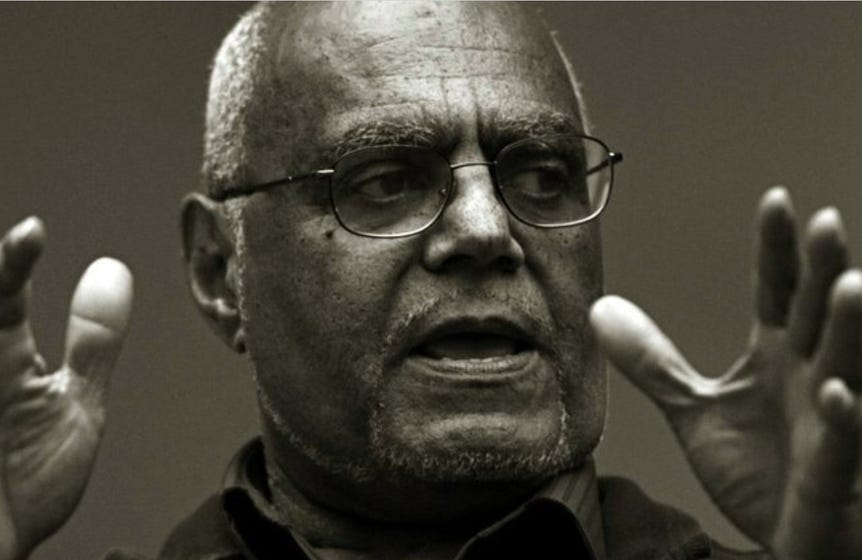

The two great endeavors to which Robert Parris Moses devoted his intellect and unforgettable presence could, at first glance, seem separated by more than two decades and some 1,500 miles. He saw them as part of the same struggle.

In 1964, he helped run Freedom Summer, which drew hundreds of white college students to Mississippi, to bolster efforts to register voters during the civil rights movement. In Cambridge in the early 1980s, Mr. Moses launched the Algebra Project, which within several years became a national program that prepares students of color and low-income students to take college-prep mathematics.

“In the ’60s we were using the right to vote as an organizing tool to get political access,” he told the Globe in 2002. “What we are doing now is using math literacy for education and economic access. The shift to an Information Age and to technology brings in math literacy. The young people, if they are going to be successful citizens, have to have math literacy. Just like the underlying issue in the voter registration movement was literacy.”

Mr. Moses, who had lived in Cambridge for many years, was 86 when he died Sunday in his Hollywood, Fla., home, his daughter Maisha Moses told The New York Times. A cause was not specified.

Though initially a volunteer in the early 1960s with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee in its voter registration efforts throughout Mississippi, Mr. Moses soon became director of another civil rights group, the Council of Federated Organizations, a cooperative effort by civil rights groups in the state, according to biographical material prepared by the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

From there Mr. Moses helped launch the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer Project, which brought Northern college students to help Black activists run voter registration campaigns.

While other Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee leaders achieved greater fame and name-recognition – such as John Lewis, the future congressman – Mr. Moses was memorable in a different way.

“He was the only one that had a kind of mystique,” Taylor Branch, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning history “Parting the Waters: America in the King Years,” told the Globe in 2001. “He was venerated.”

Those leadership qualities were present when Mr. Moses launched the Algebra Project in Cambridge. The location and challenges had changed – Mr. Moses was no longer getting arrested by Southern law enforcement – but the goals were largely similar, he said.

“In the ’60s, we seized on the right to vote in Mississippi and organized Blacks for political access, and eventually that came about,” Mr. Moses said of the Algebra Project in a 2001 Globe interview. “So today we are seizing on math literacy as a tool of organizing economic access.”

One of three siblings, Robert Parris Moses was born in Harlem, N.Y., on Jan. 23, 1935. His father, Gregory H. Moses, was a janitor, and his mother, Louise Parris Moses, was a homemaker.

“We struggled to make ends meet,” he told the Globe, “but we also had a very strong family life.”

After attending Stuyvesant High School, an examination school that is comparable to Boston Latin, Mr. Moses went to Hamilton College, where he studied philosophy. In the 2002 Globe interview, he recalled being one of only three Black students in his class.

Mr. Moses graduated in 1956 with a bachelor’s degree and received a Rhodes scholarship. The following year, he received a master’s from Harvard University.

When his mother died and his father subsequently had a breakdown, Mr. Moses settled back in New York City, where he taught mathematics at Horace Mann School in the Bronx, and among his students was future Rock and Roll Hall of Fame singer Frankie Lymon.

A visit to a relative in the South at the end of the decade spurred his interest in the civil rights movement. Mr. Moses sought the counsel of activist Bayard Rustin, who told him to spend a summer in Atlanta working at the headquarters of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Resigning from Horace Mann, Mr. Moses became a full-time activist for about four years, his life often in danger. He was arrested, beaten, and shot at.

He also was a driving force behind the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which challenged the all-white state delegation to the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City.

To avoid the Vietnam War-era draft, he later moved to Canada, where he married Janet Jemmott. With his wife, Mr. Moses moved to Tanzania, where he taught math and his family lived through part of the 1970s.

“We were way out in the boondocks,” he later told the Globe.

After President Carter granted unconditional pardons to those who had evaded the draft, Mr. Moses and his family returned to the United States and moved to Cambridge in 1976, so he could return to the doctoral studies in philosophy at Harvard he had left behind about two decades earlier, when his mother’s death and father’s illness had summoned him to New York.

In 1982, Mr. Moses was a recipient of one of the first MacArthur Foundation “genius” grants. Freed from financial concerns, he was ready to assist when Maisha, his eldest child, was set to begin eighth grade.

“My daughter was in the eighth grade and ready to do algebra, but they weren’t offering it,” he told the Globe in 1982.

Mr. Moses received permission to teach Maisha at home, and then her teacher, Mary Lou Mehrling, offered another option.

“I asked Bob if he would teach algebra in school,” she told the Globe in 1989. “And he agreed.”

Teaching Maisha and a few other students was the foundation of the Algebra Project, which quickly grew.

“My goal was math literacy,” he told the Globe.

In 2001, Mr. Moses published “Radical Equations: Math Literacy and Civil Rights,” which he wrote with Charles E. Cobb Jr.

The following year, the Education Commission of the States honored him with the James Bryant Conant Award for his work in math education. In 2006, Harvard awarded him an honorary doctorate, according to The HistoryMakers project.

Complete information about survivors and a memorial service was not immediately available. According to The New York Times, in addition to his wife and daughter, Mr. Moses leaves another daughter, Malaika; two sons, Omowale and Tabasuri; and seven grandchildren.

In 2014, Mr. Moses was prominently featured in a PBS documentary on Freedom Summer and featured as a character in “All The Way,” a play about President Lyndon B. Johnson and the civil rights movement.

The play, which won Tony Awards, was set in 1964, the Freedom Summer year. He told the Globe that he had gone to the show three times and that it captured a moment in history, even though because it was a play, it didn’t strictly and accurately adhere to every word everyone said then, including him.

By then, he was still helping run the Algebra Project as president and founder, which he saw as a continuation of what he had done in Mississippi.

“We are fighting another twist of the same struggle as to how Black people can move on to realize freedom,” he told the Globe in 2001.

This article originally appeared in the Boston Globe.