It is a politically motivated myth that Black people want to defund the police. Living in neighborhoods with significantly higher crime rates, Blacks are disproportionately impacted by all kinds of crime. Other than preventative measures and neighborhood efforts, police are the first line of defense.

In addition, many police officers emerge from the Black community. They are siblings, classmates, spouses, children, friends, and neighbors.

It is impractical and irrational to justify disdain by Americans of African descent against law enforcement.

This week I attended the second community forum sponsored by the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department in as many months. The subject for the second time was what can citizens do personally to reduce and help solve crime?

That’s a legitimate question and there is no doubt that this tremendous problem that our society faces from coast to coast will not be resolved until both law-enforcement and every day citizens assume more personal responsibility and become intimately invested. Battling crime is nothing casual, nothing trendy.

But as I pulled into the parking lot of the church at which the community discussion was held, and noticed no less than a third of the cars in the parking lot were marked or unmarked IMPD vehicles, there was this eerie sense of foreboding, this irrepressible feeling of apprehension.

Ironically, logic dictates that officers attending this kind of event reflect the brightest and best. By virtue of their participation in this important and open dialogue, they place themselves among those genuinely concerned with fulfilling the monumental mantra to protect and serve. Whether required or desired their participation was laudable.

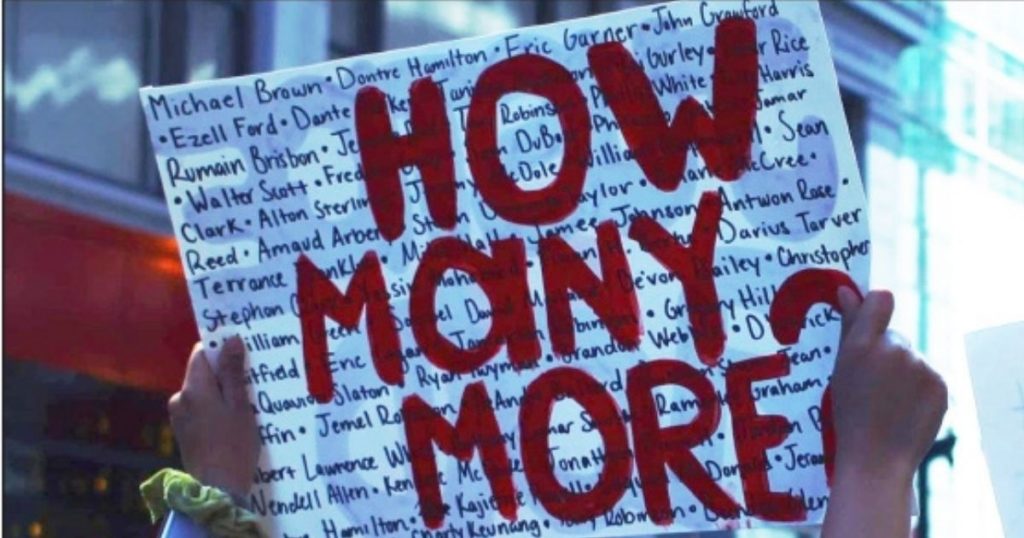

And yet it failed to nullify or offset the unnatural uneasiness that emanated in the room, even in the most congenial environment imaginable. Undoubtedly, that is why so few citizens attend. It is difficult to separate past experiences and the knowledge of adverse occurrences impacting friends, associates, family and strangers in the wake of an adverse confrontation with police.

No one is happy, for example, when they are driving and see the red or blue flashing lights come on behind them. This nation’s reality is that for the white driver a traffic stop may be an annoyance. For Black drivers, there is the dread that a mere traffic stop could rise to the level of a deathly encounter.

I won’t insult your intelligence (or my own) with statistics of how Black motorists are stopped disproportionately percentage-wise, to the white population in this country. Neither need we reiterate the fact that Blacks are more likely to be given tickets or arrested when stopped.

I won’t insult your intelligence (or my own) with statistics of how Black motorists are stopped disproportionately percentage-wise, to the white population in this country. Neither need we reiterate the fact that Blacks are more likely to be given tickets or arrested when stopped.

The trauma of the routine police interaction is difficult for Blacks to dismiss even when convening to jointly combat crime.

It is just difficult to start a conversation that so thoroughly ignores the elephant in the room. Solutions come up like better parenting, better schools, more jobs, better adult role models and more activities for youth.

Not a single one of these well-meaning proposals is invalid. But the great question becomes, if every single item on that list were implemented pervasively, would that solve the problem in its totality. It would not.

Even if the traffic stop situation does not escalate to anything extreme, there is the real possibility of verbal or physical abuse and sadly, people of color much more often are confronted with overly aggressive, antagonistic officers who frequently fuel incendiary exchanges, as rogue cops view Blacks more as suspects or perpetrators than law-abiding citizens.

People need to stop conflating this issue with the red herring of so-called Black on Black crime. First of all, an intelligent nation can have parallel dialogue without diminishing either topic. That supposition is for another session. This one, as we approach the heat of summer with so many young Black men out of school, is a matter of urgency all by itself.

Most Black people denounce criminals of every race and find criminal behavior repugnant, denouncing such savagery and disorder in the most emphatic terms.

The question is, can the law enforcement officers make the same claim, that they categorically rebuke misconduct and inappropriate behavior among their ranks; that they are willing to speak up and speak out in opposition to inappropriate behavior wherever it exists in their profession?

When that happens, if that ever happens, that will signal the genesis of meaningful and potentially lasting improvements in relationships between Black Americans and police.

Let’s not wait until the next headline-grabbing tragedy to pursue serious initiatives to improve relationships between law enforcement and the Black community. The problem is ongoing. So must be efforts to find solutions. Police community conversations must be more open and candid and consistent for any hope of results.

CIRCLE CITY CONNECTION by Vernon A. Williams is a series of essays on myriad topics that include social issues, human interest, entertainment and profiles of difference-makers who are forging change in a constantly evolving society. Williams is a 40-year veteran journalist based in Indianapolis, IN – commonly referred to as The Circle City. Send comments or questions to: [email protected].