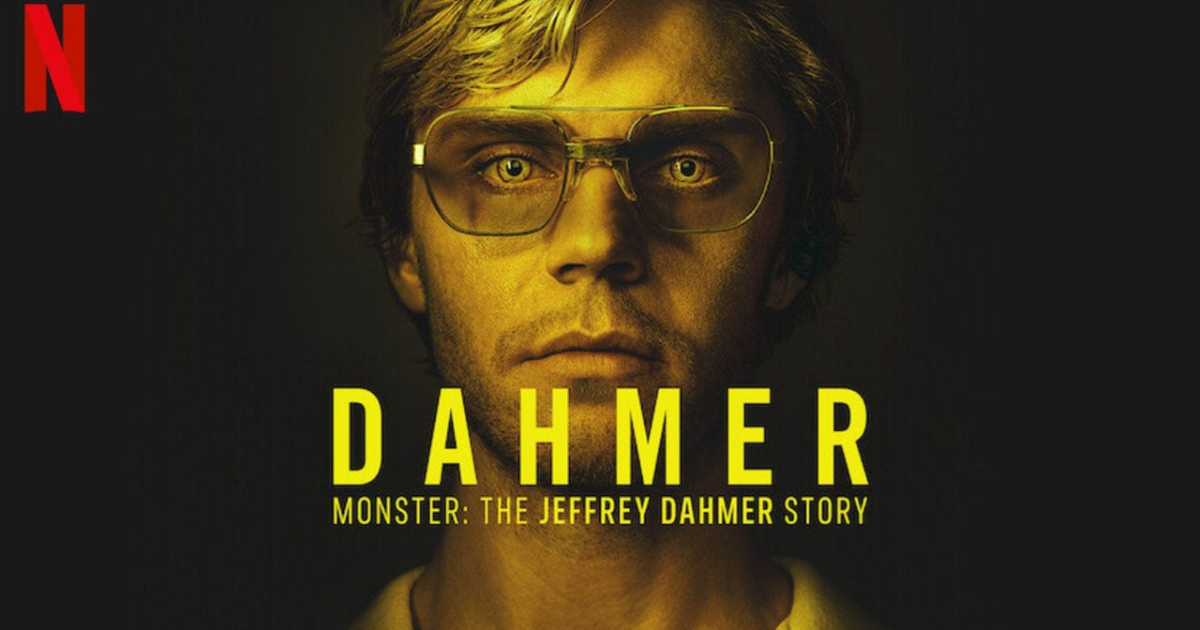

It was close to midnight recently when I turned on the television to watch with angst—more for inquiry as a writer than any interest or attraction to the grisly real-life horror—the newly released Netflix series, “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.”

I was scrolling on Twitter when I stumbled across a trending tweet: “Let’s not romanticize Jeffrey Dahmer just because he is played by Evan Peters. Remember the victims.”

For 13 years, according to police and details of the well-documented serial murder case, Dahmer preyed mostly on one of America’s most vulnerable, at least, in my view, among the most neglected: Black gay men.

Truth is, I had absolutely no desire to watch the film mostly due to my disgust over the American media’s apparent love affair with serial killers and disregard for victims and their families whose pain is relived over and over again, made worse by each new film that seems to glorify these monsters and diminish victims.

It is something with which I, as a young journalist and graduate student, have already become all too familiar as I have witnessed through reporting the trail of tears and carnage of Black lives loss to murder

As a journalist, I am drawn to their stories. To the tales of those whose lives were unmercifully stolen by killers like Jeffrey Dahmer. Drawn more to stories about humans more than monsters. I am admittedly partial, as both a journalist and as a human being, to stories that are about life, love and humanity.

And I could see no redeeming value in yet another film about Dahmer, particularly one in which I was sure his name would outshine his victims’ and by the end of which viewers would remember only one name: Dahmer’s. And after the retelling of horrific detail and evil inflicted, it would surely be crystal clear that Black lives, in film and in reality, still don’t matter.

Maybe I was wrong.

was repeatedly ignored by police.

In my desire to examine this issue as a writer—and in the journalistic fairness—I decided to watch the latest Dahmer story for as long as I could stomach it.

In the film’s opening scene, Dahmer enters a bar where mostly Black men hang out. He buys three of them drinks. Dahmer, affable and cunning, coaxes one of the men to go home with him.

Eventually, amid his series of murders, he is arrested. While shackled and in police custody, he confesses. Two detectives, one of them Black, ask why he chose these particular men? Dahmer responds, “It was just about if I thought they were beautiful…”

The Black detective refutes his claim: “I’m not buying that. You targeted your victims. You purposefully moved into an apartment in the Black community to an area that was under-patrolled and underserved. Easier to get away with things and easier to hunt?”

His words echoed my own thoughts and feelings. I had felt the same about the 51 mostly Black women in Chicago while covering that story for an undergraduate journalism project at Roosevelt University. Like Dahmer’s victims who were Black, poor and living in predominantly African American neighborhoods, most of these women were among the “invisible” societal lower class, too often considered throwaways and whose disappearances or murders do not necessitate the same media attention, or even the same police investigative effort as when whites who are murdered or reported missing.

Indeed, this point the film makes clear: That some lives are valued more than others and that the impact of racism is pervasive.

Father Michael L. Pfleger, senior pastor of The Faith Community of St. Sabina, agrees.

“It is clear that the Dahmer victims were not noticed for so long because they came from a community not only neglected, but not valued,” Pfleger told me. “Racism indeed played a major role.”

Moreover, Pfleger pointed out a stark difference between the cases of Gabby Petito, 22—a white woman reported missing while on a cross-country trip with her fiancé in September 2021 and later found murdered—and Jelani Day, 25, a Black male reported missing in Illinois in late August 2021, found dead weeks later, and whose case remains unsolved.

“After all the surface conscience raising at the murder of George Floyd, and all the Black Lives Matter hashtags, as the dust settles, we find ourselves in the same state, maybe even worse,” Pfleger said. “Black lives continue not to matter or not valued in this country.”

During my research, I struggled to find publications that listed the names of the men and boys Dahmer so brutally murdered, or stories of the human loss and of their survivors.

Where are their stories? I thought. Don’t they—we—matter?

Decades later, has anything changed?

Unfortunately, in my brown eyes, it looks much the same.

Way past midnight, I decided that I had seen enough of the Dahmer story. I clicked the power button on my TV whose glow quickly faded, sinking my living room into darkness but leaving my heart filled with the light of determination to share victims’ stories and their names.