By John W. Fountain

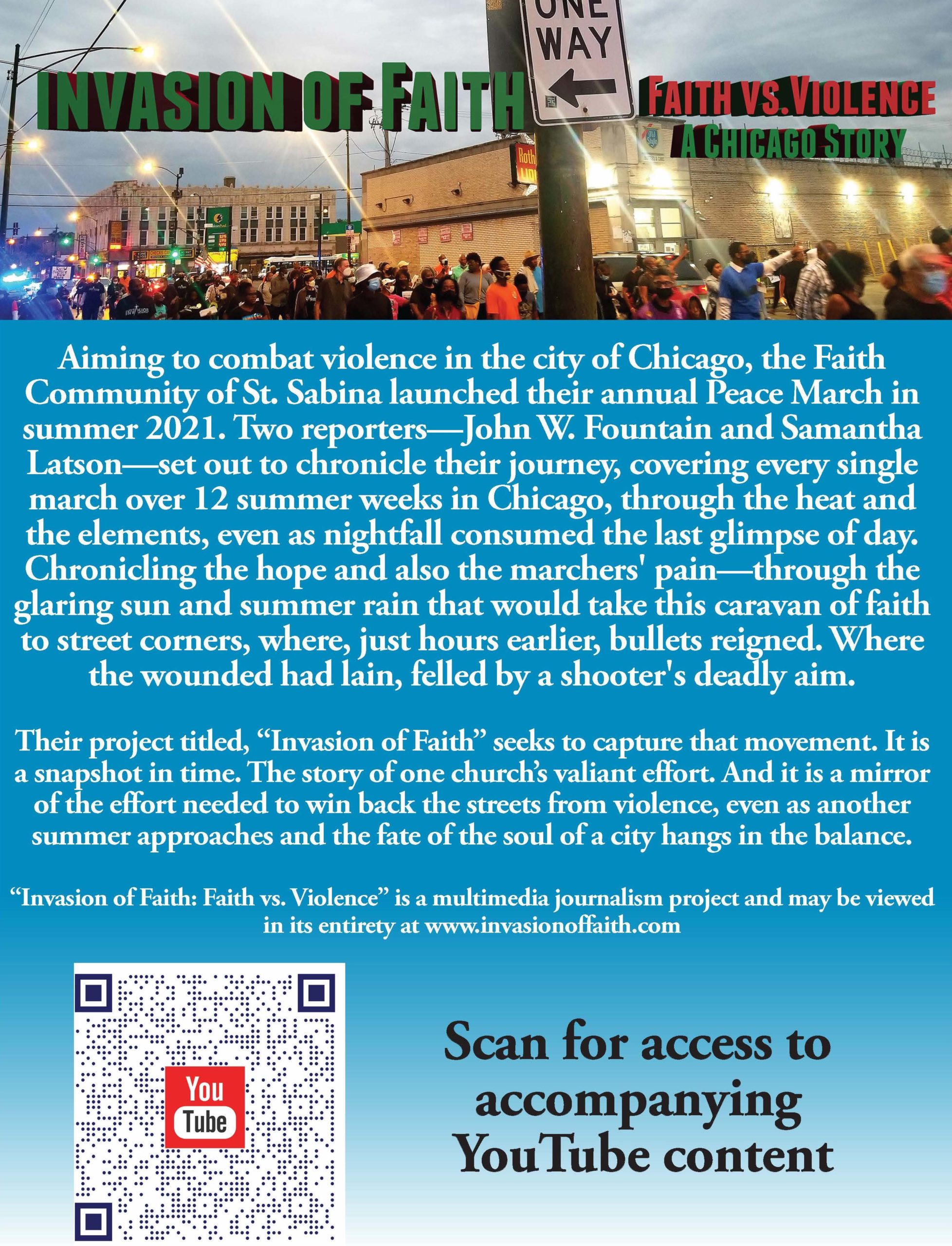

A caravan of humanity. A people of faith. It idles on 78th Place near Racine Avenue in the warm evening sun one late-summer Friday in June. Music blares from a shiny green SUV outfitted with loudspeakers that will lead them through South Side streets from the doorsteps of the Faith Community of St. Sabina.

A bought for the soul of the city, maybe even the bold makings of a revolution that will not be televised. In one corner stands Faith. In the other: Violence.

Which will win?

Two reporters set out last summer to mark their journey, covering every march over 12 hot and muggy weeks, through the elements, even as nightfall consumes the last light of day. Chronicling the hope and also the marchers’ pain—through the glaring sun and summer rain that would take this caravan of faith to perilous street corners, where, just hours earlier, bullets reigned. Where the wounded had lain, felled by a shooter’s deadly aim.

Before summer’s end, this group of the faithful would come face to face with the Death Angel who came to claim even one of their own. And more than one mother would be welcomed into the unenviable club of being a mother to a murdered son.

In the end, the summer’s violence would prove to be a foreshadowing of one of the city’s deadliest years on record.

But might prayer and faith work in the fight to end violence?

Genesis

The nuts and bolts of the Peace March are simple. It begins with marchers assembling amid a palpable cloud of excitement outside St. Sabina at 7 p.m., each Friday. Pfleger speaks briefly. His words boom over a loudspeaker about their mission—followed some- times by other church or community leaders, though words are kept to a minimum. Their mission is to pray.

All summer they march. The absence of the key players in this city is as glaring as the darkened and shuttered storefront churches with grandiose names we pass along the route each week.

There is no mayor of Chicago here. No Chicago police chief. No battalion of city council members. No show of Illinois’ two U.S. senators. Not all summer long.

No delegation of concerned U.S. congressmen from Illinois. No Cook County state’s attorney. No Cook County commissioner. No chief judge. No governor of Illinois. No Cardinal Blase Cupich of the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago.

No sense that in this city, population of 2.75 million, there exists any grand urgency or the collective will to work together to resolve the issue of violence.

The absence of city, county and state officials from St. Sabina’s marches doesn’t mean they aren’t doing anything to quell the city’s violence and murder. But it also does not reflect any visible concerted commitment to this grass- roots effort, perhaps the largest, most consistent and most vigilant by any church or pastor in Chica- go—a city that by year’s end would record more than 3,500 shootings, police records show.

Moreover, Chicago accounted for 836 of the county’s 1,087 homicides recorded in 2021—1,002 of them gun-related, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s office. The county’s gun-related homicides in 2021 broke the previous record of 881 recorded in 2020—evidence of a rise in violence and the need, many here say, for solutions. Now. But the question for me, amid an unrelenting storm of violence that resounds louder than any gunshot is: Where is the church?

“What makes us authentic Christians is not what we do in the church building but what we do when we leave because we have gathered,” Pfleger explained.

“Church is the ‘huddle’ of the game… No one comes to a game to see the huddle but look to see what they will do when they leave the huddle to build the Kingdom of God.”

I know of no institution better equipped to save souls—even the soul of a city—than the church.

Book of Acts

On one particular Friday, Pfleger breaks off from his point position in the march. He hurries, wearing his white high-top canvass Converse and black-and-white anti-violence sweatshirt, over to a group of brothers on the sidewalk while flanked by men of St. Sabina.

The smell of marijuana wafts in the wind, like the warm greeting from the white Catholic priest with a reputation in the streets as a down-to-earth preacher with a genuine love for the hood. But this is their block. The preacher’s sudden appearance out of nowhere clearly is not on their agenda and apparently no reason to breach their leisurely activities as one young man continues rolling what appears to be a blunt throughout the entire exchange.

But there is no judgment. No airs. No wincing from Pfleger who straightway launches into a cordial appeal.

Not an appeal for a contribution to a building fund. Not a membership drive. Only mutual respect.

And for Pfleger perhaps a chance to save a life, win a soul.

“Come talk to us, maybe we can help,” he says to a group of young men who look to be in their early 20s. “Maybe we can help, all right?”

One young man nods.

“So come see me,” Pfleger says, turning to another standing nearby, wearing a goatee and an untied black do-rag on his head and giving the preacher the side-eye. His skepticism about the preacher’s promises is clear. Pfleger senses as much.

“Don’t be like that, looking at me like I’m bulls——- you,” Pfleger says. “I’m telling you the truth. I’m here, ok?” he assures the young man, placing his right hand on his shoulder.

“Ok,” the young man says, nodding, looking directly into the preacher’s eyes. “I got you.”

They both smile, shake hands, embrace.

“I love you, my brother,” Pfleger tells him before pushing on. “I want you to be safe.

“Too much up in here for the world not to hear from,” Pfleger says, gently tapping the left side of the young man’s head. “OK?”

The young man nods.

(Photos: John W. Fountain and Samantha Latson)

Revelation

So what did all their marching accomplish?

“What I know is that it gave people hope,” Pfleger later told me. “We got so many folks thanking us. It also impacted the community with joy, love, and light amidst the darkness.

“We were able to get out information about our services, which each week would have folks come for help. It also brought some young brothers to us who wanted a change,” Pfleger added. “We were able to help them, mentor the mand get many jobs… Those are things I know.”

“Only God knows what the seeds planted will harvest.”

This much I know: That I witnessed by their human presence and engagement the hand of God. I felt in their uttered summer prayers a power that flowed like an electrical surge, ushering in an almost tangible spirit of peace along their trail. And I saw in the eyes of those they touched: tears, joy, relief and gratefulness that in a city where so many do nothing to try and end this scourge called violence, the church–this church–cared enough to do something.

Indeed on hot Friday nights-in a bloody city on the verge of losing its soul-by the St. Sabina caravan of believers, the seeds of peace were sown. All summer long.

“Invasion of Faith: Faith vs. Violence” is a multimedia journalism project by John W. Fountain and Samantha Latson, a graduate journalism student at Indiana University. The project may be viewed in its entirety at www.invasionoffaith.com