He was one of the last of a breed of old school Black business tycoons in Chicago. While forging a flourishing business empire and creating a vibrant social scene, the life and success of Herman Roberts provided enough material for a book about Chicago’s rich Black history.

The final chapter ended Sunday, January 31, when Roberts died peacefully just six days after celebrating his 97th birthday.

Two days before his death, Roberts’ family called the Crusader office to say the beloved husband, father and trailblazing business tycoon was nearing the end of his life. His wife, Sonja, said her husband had stopped speaking two weeks ago. He died of natural causes last weekend.

As Black History Month gets underway, the story of Herman Roberts is an inspiring lesson. His is the story of a young man who, without a high school diploma, became one of the city’s most successful businessmen, providing both famous and ordinary Blacks places at which to wine, dine and socialize, when they were not welcomed in white neighborhoods.

In his lifetime Roberts was among a fraternity of Black tycoons in Chicago who achieved big success with very little means. Roberts came from the mold that gave Black Chicago Ebony founder John H. Johnson, Ultra Sheen Hair Products tycoon George Johnson, real estate mogul Dempsey Travis, and banker Jesse Binga.

To many, he was known as the well-dressed impresario and socialite who wore the finest suits and shoes. Some did not like his flamboyance, but he won many over as a hardworking businessman who met the needs of Chicago’s Black community as it suffered from racist policies during segregation.

Since 1965 he, along with his wife Sonja, raised son Rodney Roberts and daughters Ewan “Scooter” Roberts, Hermia Roberts and Candace Will Iams. Herman Roberts had more children from other relationships.

Roberts lived many of his final years in Woodlawn, a neighborhood that is now dramatically different from what it was during his years as a business tycoon.

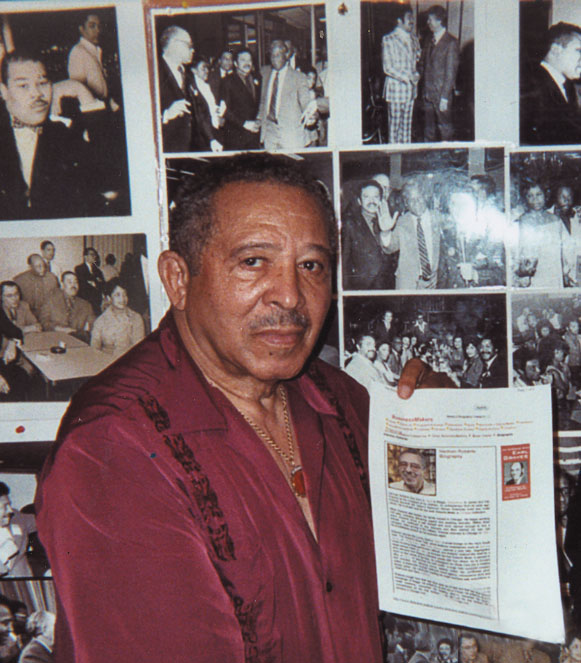

In 2016, I sat down with Roberts in his home just several blocks south of the Crusader office, for a two-hour interview. Then he was 93, but he still had vivid memories of mingling with the Who’s Who of Black Chicago and Black America.

The wall in his living room was covered with his personal collection of Black and white photos of Sam Cooke, Muhammad Ali, Sammy Davis Jr, Lou Rawls, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, and many more easily recognizable celebrities.

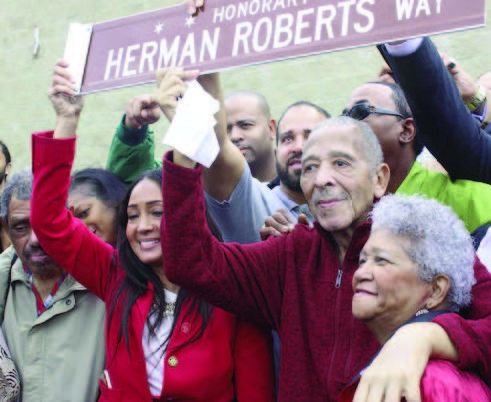

A week after the Crusader interview in 2016, during an emotional ceremony, Roberts was given the honorary street sign “Herman Roberts Way” at 65th and King Drive. That same day, the late Crusader founders, Balm L. Leavell and Joseph Jefferson were given an honorary street sign outside the Crusader office near 64th and King Drive.

But Roberts’ biggest pride and joy was his business empire that included a portfolio of taxi cabs, motels, and nightclubs and lounges. He owned six Roberts Motels, one was in Gary, Indiana. He owned the Roberts Cab Company, which at one point boasted a fleet of 40 taxis.

He was born the son of a sharecropper in 1924 in Beggs, Oklahoma. It’s a small town whose population grew to five thousand when oil production peaked two years after Roberts’ birth. When he was just 12 years old, Roberts moved to Chicago as the Great Migration movement cooled from the Great Depression.

After selling Black newspapers on the city’s streets, in 1939 Roberts’ brother Colvin introduced him to a friend who owned several taxi cabs and offered him a job washing the cars for little money. As a hard worker, Roberts built enough trust with the cab owners that he could drive cars without getting in trouble.

By the time he was 18, Roberts had saved up enough money to purchase his own taxi and license. The company grew to 40 taxicabs in several years. By 1944 the fleet would be known as the Roberts Cab Company. It operated out of a garage on 67th Street and King Drive, a site that would become the future location of his iconic Roberts Show Lounge, and is now the home of the New Beginnings Church, headed by Reverend Corey Brooks.

Success with the taxi business would drive Roberts to greater visions. After driving many passengers to nightclubs and lounges, Roberts realized the potential of having a dazzling club where Blacks on the South Side could relax and be entertained. In 1953, the Lucky Spot was born. It was a small lounge at 602 E. 71st St.

In 1954, he opened the Roberts Show Club, a venue that drew famous Black entertainers such as Count Basie, Sarah Vaughn, and Sammy Davis Jr. The club also helped launched the careers of Redd Foxx, Della Reese, George Kirby, and comedian Dick Gregory. At one of Roberts’ clubs, Playboy founder Hugh Hefner discovered Gregory and the rest is history.

In addition to a thriving cab company and nightclub business, Roberts opened six motels on the South Side starting in 1960. One of them is now the Best Motel at 66th and King Drive. In its heyday it was considered the classiest on the South Side. Roberts would also own bowling alleys, ice skating rinks and gas stations.

Years before the Civil Rights Movement was in the public’s conscience, Black entertainers and citizens were not allowed to stay at white-owned hotels. During that time Roberts built the Roberts Motel at 6625 South Parkway, now King Drive. The new motel was across the street from his Roberts Show Club. After achieving overwhelming success with that motel, he built two more, at 38th and Michigan, a fourth at 79th and Vincennes, and another at 65th and South Parkway (King Drive).

His pride and joy, the “500 Room,” a motel housing 250 guest rooms, three penthouse party suites, the 300-seat bar and lounge, travel agency, restaurant, and beauty shop, was opened in 1970. The chandeliered ballroom and winding staircase offered opportunities for pride-filled parties and social and political events. Over the years, Chicago mayors and Illinois governors were just some of the political figures who visited the establishment.

In 1981, Roberts struck oil on land he owned in Oklahoma. He also built a home and opened a motel in his native Beggs, Oklahoma.

Roberts is also credited with giving thousands of jobs to Blacks in Chicago who had few employments and economic opportunities in a city that grew increasingly segregated over the years.

Roberts’ motels and businesses would provide Roberts with an affluent life-style that included a 2,000-acre ranch outside Tulsa, Oklahoma. His wife, Sonja, told the Crusader that she and her husband twice brought 50 children and teens from throughout Chicago to the ranch for a weekend of fun and inspiration.

In Gary, retired auto executive Nate Cain remembers when he worked as a manager for two years at Roberts Motel on Melton Avenue in 1974 during Mayor Richard Gordon Hatcher’s administration. Cain told the Crusader that the motel had 96 rooms, a restaurant, a ballroom, and a nightclub. Cain said R&B singing groups the Dells and the Manhattan’s, along with singer Jerry Butler, were among the many performers at the Roberts Motel in Gary.

He also said Muhammad Ali, WVON legend Cliff Kelley and Reverend Jesse Jackson visited the place. Cain said the late singer, Walter Jackson, whose song “Feelings” was a top hit, was once a tenant of the motel. To Cain, managing the Roberts Motel was an exciting time in his life that led to bigger jobs as an auto executive at Tyson Ford in Gary. He said the last time he spoke to Roberts was five years ago. “Herman was a good person to work for,” Cain said. “He was just a good guy.”

During a tribute to Roberts’ life on Tuesday, February 2, WVON was flooded with calls from listeners who shared their memories of Roberts and his contributions to Black Chicago.

Roberts’ wife, Sonja, has been with him off and on for 56 years. They had been married for years. She met him in 1965 after she was given a part-time job at one of his businesses. Roberts [Sonja] said she had a friend who was Herman’s secretary. Roberts said Herman asked her on a date, but she did not accept his offer unless the secretary went with them. Roberts finally accepted his offer after later visiting Herman on his ranch in Oklahoma.

“He was very dirty and wearing a cowboy hat,” Sonja recalled. “I was shocked to see a man who was usually dressed in sharp suits and shoes. But that made me see a different side of him.”

Sonja Roberts recalled an event in 1977 at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, where Frank Sinatra and Cary Grant were in attendance. Grant sat down next to Sonja, who said Herman looked at a gray-haired Grant and asked, “Would you like to take a picture of me?” Sonja said he did this everywhere he went. She described her husband as “a family man.”

“On Sundays, he would go to church and come home, spend time with his family and eat dinner. Everyone knew him as a businessman, but few knew him as a family man.”

In the 1990s Roberts lost many of his properties during a tax dispute with the city. Many believe that Roberts like other Black entrepreneurs became victims of the shady politics at City Hall.

During the 2016 interview with the Crusader, Roberts said his businesses began to decline when then-President Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The new act helped end segregation by prohibiting discrimination in many places where Blacks were once shut out. With their freedom, Black entertainers and residents went to other businesses in other neighborhoods and Roberts’ businesses declined. “The Civil Acts of 1964 hurt me more than it helped,” Roberts told the Crusader.

Funeral services for Roberts were scheduled in Las Vegas on Friday, February 5. A showman who became a pioneering business leader and Black historian, Roberts’ services in Las Vegas were expected to be a fitting acknowledgement of his life.