By A. L. Smith – Contributing Writer

When most of us think of today’s National Football League (NFL), we see a player-diverse, multi-racial sports league, which is now predominately filled with 75 percent Black athletes representing professional teams across the United States.

This was not always the case. In fact, for many divisive years, preceding the modern-day civil rights era, talented Blacks were specifically excluded from joining the NFL due to the racially-tinged period in American history which marginalized African-Americans in virtually every field of endeavor,

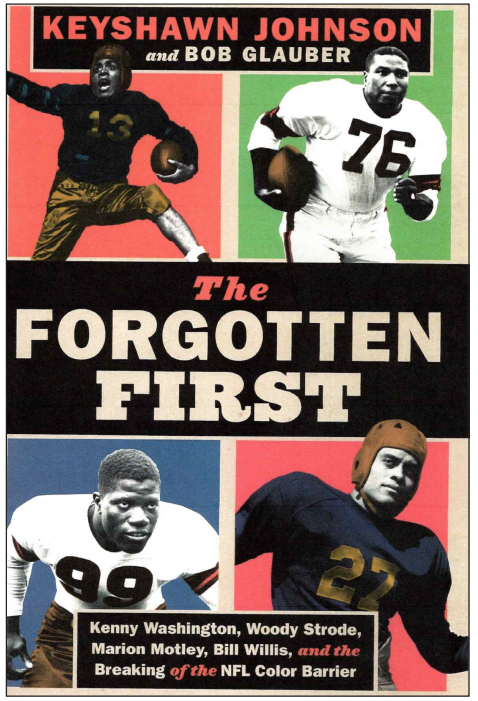

Four Black men, Woody Strode, Kenny Washington, Marion Motley and William ‘Bill’ Willis provide the historical foundation upon which today’s generations of professional African-American NFL players stand.

And it took a small group of activist Black journalists across the U.S., in particular one brave Black man, himself an acclaimed, former award-winning college athlete, to kick open the doors to sports equality.

Who was he? His name was William Claire ‘Halley’ Harding.

Considerable credit, however belated, must be attributed to “this courageous left-leaning radical” for profoundly changing the course of American sports history by organizing the national Black press to lead public discourse decrying and eventually overturning the Jim Crow exclusion of Black players from the professional sports arena.

The late Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. once opined that “…The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands during times of challenge and controversy…”

Although you’ve probably never heard of Harding until now, reading this article, know this! William Claire ‘Halley’ Harding from the start of his career in the late 1930s through the mid-1960s was a dynamic man who thrived on civic challenges and stood tall in confronting racial controversy. He was a prolific Black sports journalist who fearlessly advanced the cause of racial integration of the National Football League (NFL), against all odds.

In the annals of modern-day NFL football history, the name William Claire ‘Halley’ Harding is almost unknown, forgotten and in some ways cast aside, into the dustbin of little-remembered sports contributors of the past.

But thankfully, not anymore.

Today, renewed interest about Harding’s pre-eminent sports writing career has been on a long overdue, yet well-deserved, rocket-velocity, upward bound trajectory. That trajectory is fueled by current, reemerging civil-rights issues intertwined with a growing awareness of his legacy of equity-focused leadership.

According to financial industry analysts Deloitte, an American and worldwide sports industry mega-behemoth: Once little respected, today football remains king, unrivaled as the most popular sport in the United States.

Global revenues for this sport equal an astounding $28 billion annually. Annual television viewership of the National Football League (NFL) hovers at over 17.1 million fans.

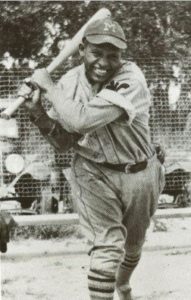

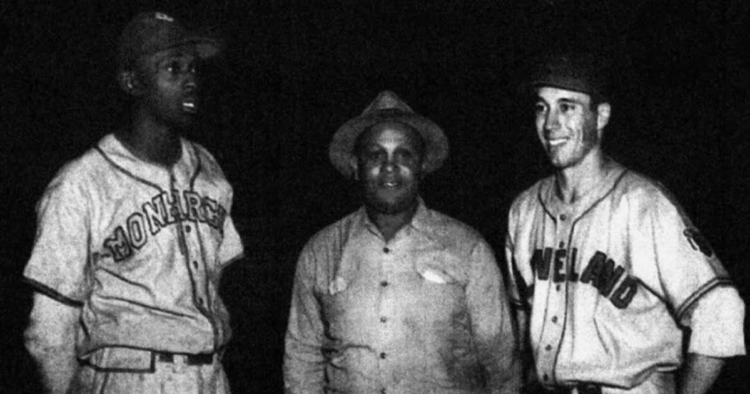

William Claire ‘Halley’ Harding (November 13, 1904 – April 1, 1967), was among a post-World War II generation of fiery proactive Black journalists and activists who reached out, stood tall, and impacted social change by speaking up on issues which needed addressing in the emerging, civil-rights movement discourse. Born in Wichita, Kansas, Harding attended Knox College and Wilberforce University. He was a triple-threat athlete who set records in baseball, football, and basketball. The avid sports lover was an incredibly gifted competitor who played college football at several Black colleges as an exceptional quarterback and punter. He played professional basketball for the Harlem Rens, and in 1926 made his Negro League baseball debut for the Indianapolis ABCs. He also played with the likes of Satchel Paige. He was an American Negro League shortstop from 1926 to 1937.

Further, Halley Harding was part of an all-Black basketball team, a forerunner to the Harlem Globetrotters. He also played semi-pro football on two all-Black teams during the time Blacks were “race-outlawed” from the NFL. He could have pioneered in several professional sports, had he chosen to do so.

Another little-known fact is that the multi-talented Harding also performed minor roles in Hollywood Black movies during 1939 and 1940. Following his diverse early athletic career, Harding operated as a sportswriter and editor for the Los Angeles Tribune, the Los Angeles Sentinel, and later the Chicago Crusader newspapers. He was a leading voice in advocating for the integration of the Los Angeles Rams and the National Football League. Harding died in Chicago in 1967 at age 62.

“Halley Harding was my uncle and one of the greatest journalistic freedom fighters of his era, who helped us make tremendous strides in opening up the doors of opportunity for Blacks in professional sports,” said former Chicagoan and now Los Angeles-based nephew, Geoff Harding.

During Harding’s career, and after a brief period of limited integration in the 1920s when the NFL was originally formed, few Black athletes were allowed to be part of the growing professional league. He would surely be shocked today to see an estimated majority of all football players are Black.

Harding was a pioneer, a crusading Black reporter whose brave sports related racial equity advocacy has been overlooked. What he did for Black athletes, to integrate baseball and especially the National Football League (NFL), during the post-World War II era deserves acclaim and respect.

Harding and other Black journalists pushed hard during 1946 for the integration of the newly relocated Rams to Los Angeles, a year before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947.

He was bold, tough, and always ready to take the civil-rights struggle to the next level and challenge the limits of racial exclusion of Blacks, anywhere and everywhere, especially in sports.

Harding grew up experiencing the wealth gap firsthand. Early on, he developed a passion for sports and journalistic advocacy, guided by his quest to spread equity for others like him, from underserved areas, who had been negatively impacted by racism.

“He wanted to be that era’s agent for change. And even today we desperately need those who have the ability to create opportunities for those who still remain marginalized. I wish he could see the success status of today’s African-Americans in football and other sports arenas,” added Geoff Harding.

Halley Harding was enthralled by sports from a young age, an interest that endured throughout his lifetime. He saw firsthand the potential championship power exhibited by Black players being unfairly denied access in all sports. That’s why Harding relentlessly focused his news career efforts in rectifying these injustices. His efforts ultimately resulted in a massive national Black media fallout, galvanized by emerging post World War II civil-rights advocacy that forever changed the course of professional sports.

First, a bit of football history.

As a sport, the roots of pro football (which evolved into the NFL) originated in 1869, shortly following the end of slavery, from a mixture of soccer and rugby. Blacks were banned from the pre-NFL teams during their formative years.

Charles Follis is recognized as the first known Black man to play pro football, with the Shelby Athletic Club in 1902. After Follis retired from the sport in 1906, his replacement was Charles “Doc” Baker, the second Black pro football player, serving two years as a running back with the Akron Indians. Another Black running back, Henry McDonald, signed with the Rochester Jeffersons in 1911.

The sport’s first governing organization, the American Professional Football Association (APFA), started in 1919. Three years later, it was replaced by the National Football League (NFL). Ironically, both leagues hired Black players.

Robert “Rube” Marshall played tight end for the Rock Island Independents from 1919 to 1921, and Frederick “Fritz” Pollard played three years with the Akron Pros, later becoming football’s first Black professional head coach with Akron in 1920.

Many other African Americans moved into professional football throughout the 1920s, including Paul Robeson, Jay “Inky” Williams, Harold Bradley, John Shelbourne, Joe Lillard, James Turner, Edward “Sol” Butler, Dick Hudson, David Myers, and Duke Slater. They were all stand-out players for teams in both leagues, the APFA and the NFL.

Then racial sports trouble started. Suddenly, after 31 years of limited integration, the NFL excluded Black athletes from participating in league play in 1934, after the widely accepted, but never formally codified creation of an ‘informal gentleman’s agreement’ among white team owners. Football’s Black player ban lasted until 1946.

Yes, it’s true! For 12 years, from 1934 to 1946, there were no Black players in the NFL.

Interestingly, the story goes that several of the most famous owners in the league’s history – allegedly led by George Preston Marshall, George “Papa Bear” Halas (owner of the Chicago Bears), Art Rooney, and Wellington Mara among them – had established a strictly enforced, unofficial, unspoken ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ treaty to ban Black players.

William Claire Halley Harding immediately challenged what he felt was an unacceptably egregious insult to Black Americans as a whole and sports fans in particular.

He angrily, repeatedly, and forcefully opined in his news columns that it was strange in ‘the land of the free and home of the brave’ that Black athletes could be quickly conscripted to put their lives on the line and fight for ‘freedom’ in the World War, yet their talents were routinely overlooked, denied, and unable to be displayed on U.S. football sports teams.

The fact: Halley Hardy was the leading proponent who convinced the local and national Black sports press contingents to keep pressuring the Rams for racial inclusion.

The winning success strategy? Information and an urgent call for Black community action.

The Rams team was requesting to lease the Los Angeles Coliseum, which had been built with public government funds. In response, the NAACP, churches, block clubs and fraternal and social organizations marched, protested, called, sent thousands of opposition letters to local officials, and threatened fan stadium boycotts unless Blacks were allowed on the team.

Still, league owners resisted change. Two major instigators were owners Marshall and Halas, according to reports. Exasperated, Halley pulled a last-ditch public offensive to make his point.

“One of the hallmarks of his career was delivering an incredible speech which wowed local sports and elected officials – even impressing his critics, and successfully paved the way to integration of professional football for Black people,” fondly reminisced his nephew.

On January 15, 1946, ironically the birthdate of another man who would profoundly impact the civil-rights movement, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Halley Harding, then sports editor of the Black-owned Los Angeles Tribune, wrote an editorial. In it he passionately opined about the social hypocrisy of conscripting legions of young Black men into the U.S. military, to put their lives on the line to serve America, yet they were not allowed to cross the end zone finish line in American football.

Harding made a strong case for teams to include Black players if they wanted to use the publicly-owned and financed Coliseum stadium. To secure the hard-fought victory, Harding single-handedly forced the Rams officials to put their integration pledge in writing, and after a deluge of negative local and growing national publicity, they did.

Kenny Washington and Woody Strobe were soon after signed by the L.A. Rams, historically becoming among the first four Black players who finally emerged triumphant and broke apart the NFL’s longstanding racial color line.

Then Cleveland signed Bill Willis and Marion Motley. Next in line to reverse this abomination, were the New York Giants (Emlen Tunnell) and the Detroit Lions. Notably, despite growing national outrage these were the only other NFL teams to embrace Black players during the decade of the 1940s.

‘Halley’ Harding

Writing for the Black owned Los Angeles Tribune, sports journalist William Claire ‘Halley’ Harding was the key leader in the long fight to force professional football to sign Black players, amplifying the critical advocacy role that the Black Press has played in confronting national issues, and continues to play today.

Among other major ground-breaking cultural and racial matters, promoting the final erasure of the unofficial ‘color ban’ in professional football was another important thing the Black Press did in advancing social equality and fomenting lasting change in this country. It was similar to the Black publications’ equally successful mission to integrate the U.S. military, which many historians frequently note was an important achievement in which the Black Press played a huge role.

Halley’s nephew, Geoff Harding, fondly recalls the man who fiercely loved his people and football.

“Black empowerment and sports equality was the heart, spirit, and soul of my uncle. All he wanted to do was elevate Black people,” Harding said.

“As a youngster, I didn’t always understand, but as I matured, I saw first-hand the injustices, racial discrimination, and disrespect we endure, and the unnecessary hard times we experience throughout our lives. Then it became clear to me why he steadfastly refused to collapse under enormous pressure. I’ll always admire him for his courage and commitment to social change.”

“He never backed down. He never crumbled. He got up every day and fought the good fight for Black athletic advancement in pro sports, his family, and our community no matter what, even when it sometimes seemed like he was fighting alone. He taught me to stand strong and be accountable for my beliefs and inalienable rights despite all odds.”

Recently, Harding’s legacy was posthumously honored during the 2022 National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) convention, where he was among those bestowed the prestigious NABJ Sports Task Force’s Sam Lacy Pioneer Award.

Dorothy Leavell, the widely-respected publisher and owner of Chicago-based Black news weekly the Chicago Crusader, for which Harding wrote for many years, recounts his numerous civic contributions:

“Halley was a bravely talented writer and savvy innovator. What he essentially did was strategically use the power of Black media to kick open the door to the money, power, and prestige of the NFL for generations of football minority sports stars, many of whom unfortunately never even knew his name.”

Continues Leavell, “Everybody knew Halley – – and during those racially-charged civil-rights times, many white sports franchise owners despised him.

“He was the sportswriter forerunner who advanced the status of Black inclusion and equality in today’s multi-billion-dollar football sports industry.”

Leavell concluded, “I’m proud that the NABJ was committed to changing that narrative and elevating his life and career defining, cutting-edge, journalistic radicalism and integrity.”

Nephew Geoff Harding, who still today idolizes his uncle’s courage, cultural convictions, and strong family connection, says, “I miss him terribly, but I know that my dear uncle Halley is being celebrated up in football heaven with those legendary, groundbreaking Black football giants who destroyed the once longstanding, blatantly unfair ‘color barrier’ in professional football, thanks in part to his relentless articles, op-eds and public testimony demanding immediate and substantive change for Black competitors.”

Geoff, whose career as a journalist has included stints with CNN and Newsweek, further relates learning valuable life lessons.

“Halley Harding was a fearless warrior for better opportunities and working conditions for Blacks in the sports arena. We can all thank him for dedicating his entire professional life to breaking down barriers for working African-American athletes.”

“Harding is synonymous with the modern-day makeup of the National Football League (NFL) and other sports,” said Geoff Harding.

“Halley embraced and came to embody the essence of Dr. King’s dream. While there’s still more work to be done, in many ways, anyone would be hard-pressed to find a sportswriter who had a bigger impact in shaping the racial equity influence within the NFL organization as we know it today, than did William Claire ‘Halley’ Harding.”

Now that’s significant. William Claire ‘Halley’ Harding left an impressive legacy worthy of celebration, recognition, and a maybe even a special place of honor in the NFL Hall of Fame.