Center, left to right: Lori White, Gregory Washington, William Tate IV, and Laurie A. Carter

Bottom, left to right: Brian O. Hemphill, Vincent D. Rougeau, and Michael V. Drake

In the past two years, there have been numerous firsts with African Americans selected as presidents of predominantly white institutions (PWIs). In 2020, we saw the appointments of Jonathan Holloway of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey; Lynn Wooten of Simmons University in Boston, Massachusetts; Dwight A. McBride of The New School in New York City; Darryll J. Pines of the University of Maryland; Lori Whiteof DePauw University in Green Castle, Indiana; and Gregory Washington of George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. The following year, in 2021, there were more appointments, including William Tate IV at Louisiana State University; Laurie A. Carter at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin; Brian O. Hemphill at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia; Vincent D. Rougeau at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts; and Michael V. Drake at the University of California—one of the largest university systems run by an African American—after he served successfully as president of Ohio State University from 2014 to 2020.

With the pandemic affecting a second school year, these presidents have a lot more on their plate than most assuming a new presidency during the pre-pandemic era. President Jonathan Holloway of Rutgers University—which, in 2021, admitted the largest first-year class in the university’s history and one if its most diverse—reflected on the times: “No one’s written a playbook for this… situation. For me, I think this is a very special moment in higher education, especially as it relates to all the dynamics related to the inequities that this has exposed, whether it’s through health issues or racial issues or socio-economic issues. Now, we have a chance to actually do a much better job educating our respective communities about how we got to this kind of moment and what we can do on the other side of it.”[1] As we progress through a second pandemic academic year, and all the issues facing those in higher education including union issues, critical race theory, and the recent scandals and firings of the presidents of the University of Michigan and Florida International University, the challenges and complexities of leading these institutions will shape the broader future of higher education, and so will the presence of African American presidents of predominantly white institutions.

These appointments are in direct contrast to the history of higher educational leadership in the United States. Melandie Katrice McGee, author of ‘A Mixed Methods Exploration of Black Presidents Appointed to Predominantly White Institutions,’ explained in her study: “Those administering higher education… were primarily White people… Black institutions… were led by White presidents and, at the beginning, all White teachers. Black faculty were gradually added while Black presidents were appointed at a much slower pace… As Black students began to gain entrance to previously all-White institutions, so too did Black professional staff.”[2] With institutions slow to hire even black staff, the office of the president was not anything that an African American could aspire to attain. In fact, between 1945 and 1947, African Americans represented just .18% of faculty members from 178 PWIs surveyed. When 130 PWIs were surveyed in 1967 and 1968, that number grew to only 1.3%.[3]

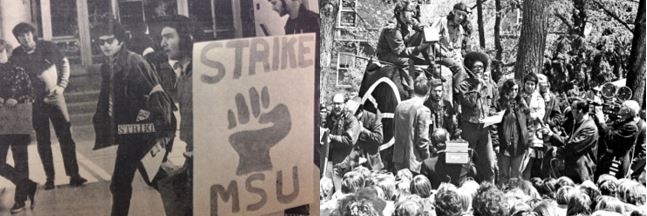

That is why the appointment of HistoryMaker Clifton Wharton, Jr. as the first African American to lead a major research university at Michigan State University in 1970, was simply extraordinary. Wharton had been the first African American to earn a master’s degree in international affairs from Johns Hopkins University and his father, diplomat Clifton R. Wharton, Sr., had been the first African American to pass the Foreign Service exam before becoming ambassador to Norway in 1961. Wharton, Jr., in his 2006 interview, recalled his appointment as president of Michigan State: “There were certain people… who pushed for me… the board at Michigan State… three of the Democrats wanted to have as the next president Soapy Williams [G. Mennen Williams], the former governor of Michigan… up to the last minute, they tried everything they could, these three, to stop my appointment… my name was submitted by one of the blacks, who is a Democrat. He nominated me for the position… Blanche Martin… [a] dentist.”[4]

Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and Michigan State alumnus George White of the L.A. Times, spoke of this time: “At the time when I was a student, from ’71 [1971] to ’75 [1975], we had the largest black student population at a predominantly white institution… it was the height of the protest period against the Vietnam War… I was on Clifton Wharton’s… student advisory board… state police came on campus, and there were clashes… And we said… just let the students let the steam off… people had a right to assemble and to protest, and he [Wharton] took our advice… he was a brilliant guy.”[5] This position was the first of many historic ones for Wharton, as he subsequently served from 1978 to 1987 as chancellor of the 64-campus State University of New York system, the first African American to head the largest university system in the nation; in 1982 he was named chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation; and, in 1987, he became CEO of TIAA-CREF (now TIAA), making him the first African American CEO of a Fortune 500 company.

Georgetown University’s twenty-ninth president, Patrick Francis Healy, who served from 1873 until 1882, could be considered the first in the country, but he was passing as white or at least not acknowledging his mixed-race heritage. White collar lawyer Theodore V. Wells, Jr. explained: “James and Patrick Healy were the sons of a white Irishman [Michael Healy] who settled in Georgia and… married the slave [Mary Eliza Healy]. It was against… the laws in Georgia, but they got married. They sent their kids to a private school in New York… James went on to become the bishop of Maine [Bishop of Portland, Maine, and the first Black Catholic bishop in the U.S.] and Patrick became the president of Georgetown.”[6] Healy was one-sixteenth black, the first African American to become a Jesuit, to earn a Ph.D., and to become president of a predominately white college or university-all recognitions that have been made posthumously.

In 1966, ninety-three years after Healy’s appointment, James Allen Colston became president of Bronx Community College, a PWI, where he served as president for the next decade. Colston had previously served as president of several HBCUs: Bethune-Cookman College, Georgia State College (present-day Savannah State University), and Tennessee’s Knoxville College. That same year, Paul Phillips Cooke became president of the District of Columbia Teachers College, an institution that emerged after Brown v. Board of Education integrated the white and black teachers’ colleges in D.C. Cooke recalled in his 2004 interview: “After… going from an instructor to assistant professor, to associate professor, to a full professor, to an acting dean one time. I become president, September 1st, 1966… during the eight years I was president. Enrollment went from 1,250 to more than 4,000. We were attracting students to come to the Teachers College.”[7]

During the 1970s, thirty African Americans were appointed to head PWIs, followed by sixty-one in the 1980s, and 144 in the 1990s.[8] 1990 saw the first African American woman named president of a major U.S. university with the appointment of Marguerite Ross Barnett to the University of Houston. During that period, Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts, senior pastor of the historic Abyssinian Baptist Church, also served as president of the State University of New York College at Old Westbury from 1999 to 2020. Of his tenure, he explained: “We built five new dormitories; we built a new student union building; we brought in several million dollars in new technology. The enrollment is now going up… but I’m a black man. And the racism is unbelievable even among the faculty.”[9]

Ruth Simmons, the current president of Prairie View A&M University, an HBCU, made groundbreaking history in the Ivy League and higher education at large when she was appointed as the first African American president of Smith College in 1995; then six years later in 2001, as the first African American president of an Ivy League College when she became president of Brown University. Upon her appointment, she recalled: “I had a mentor who was wonderful for me, who encouraged me along the way. But he said, ‘Ruth, you certainly have the ability to become a college president; but you’ll never become president, of course, of an Ivy League university. But you can become president of a college.’”[10] At Brown, Simmons spearheaded an effort to investigate Brown University’s historical relationship to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade—something that was viewed as controversial that also “opened the way for colleges and universities, North and South [i.e., Columbia University, Harvard University, Yale University, University of Maryland, University of North Carolina, and Emory University, College of William & Mary, etc.], to do the same… Over the past decade, colleges and universities have marked their history with slavery through memorials, courses and student projects, archival exhibits, and apologies for their past support of the institution.”[11]

In 1999, HistoryMaker Shirley Ann Jackson, the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in physics from MIT, then became the first woman and first African American president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, the oldest technological university in the Western hemisphere. Jackson still serves in this role, and in her 2006 interview, she reflected on her legacy: “I changed institutions and put them on a trajectory to address the issues of the twenty-first century… I’ve opened doors for those who may not have felt… they could have a life or career like mine… I started on a little street in Washington, D.C., in segregated public schools. Here I am, but I had great parents and a confluence of events, the Brown [Brown vs. Board of Education, 1954] decision, the Sputnik launch[1957], and I was willing to step through the door when it opened.”[12]

Joyce F. Brown spoke of undergoing scrutiny and having her qualifications called into question when she became the first African American and first woman president of the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York: “The media types decided that because my husband [HistoryMaker H. Carl McCall] … was running for governor that the sitting governor who was his opponent would name me president so that… my husband wouldn’t run or wouldn’t attack… [They] tried to denigrate thirty years of work that led me up to being eligible to compete for the job.”[13] Brown began her career in administration at the City University of New York (CUNY) where she later served on the faculty in the Graduate Center. She also served as New York City Mayor David Dinkins’ deputy mayor before becoming president of FIT in 1998, where she continues today.

In 2004, HistoryMaker Ron Crutcher became the first African American president of Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, after serving as an academic administrator and music professor at the University of Texas, Austin and Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Crutcher shared: “What I tried to do there was to help the college understand how to… develop diversity as an asset as something that would enrich… In terms of fundraising… I raised more money than any other president in the history of that college.”[14] Serving Wheaton for a decade, Crutcher was subsequently named the first African American president of the University of Richmond in 2015 and retired in August of 2021. He reflected on his time at Richmond, which included debates around race with the decision not to rename buildings named for segregationists and slave owners: “When we started out… my philosophy [was] that we can learn from this situation… Nearly 30% of our students are domestic students of color… but you could have 50% students of color and still have a campus that’s hostile to students of color. I’m more interested in ensuring that across the university, people at all levels have bought into our values of diversity, equity and inclusion and belonging.”[15]

Three years after Crutcher’s appointment to Wheaton, HistoryMaker J. Keith Motley was hired as chancellor of the University of Massachusetts Boston. In his 2018 interview, he explained his trajectory: “I was Dean of Student Services [at Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts] and I was… going participating in the president’s groups… because of a mentor of mine, Dr. David Carter… he was the longest serving President in New England [as president of Eastern Connecticut State University for eighteen years] … who happened to be African American. He got me into a program I wasn’t supposed to be able to go to… a woman from the University of Massachusetts… talks to me… her name is Jo Ann Gora… she was chancellor … She says… ‘with the kind of experiences you’ve had, with the kind of opportunities you’ve had to learn; with your experience in Boston, and your networks… you could come here and actually be the chancellor… and I really want you to come work with me, and we can learn from each other.’”[16]

John Williams

Bottom, left to right: Paula Johnson, Isiaah Crawford, Melvin Oliver, Gary S. May, and Thomas A. Parham

Other black presidents of predominately white colleges and universities include Rodney Bennett, who was appointed in 2013 as president of the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg, becoming the first African American president of any of the major five colleges in Mississippi. That same year, Valerie Smith took the helm of Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania and Sean Decatur was named president of Kenyon College in Ohio. Trinity College in Connecticut selected HistoryMaker Joanne Berger-Sweeney in 2014, and John Williams became president of Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania in 2015. The following year, Paula Johnson was named president of Wellesley College in Massachusetts, Isiaah Crawford became president of the University of Puget Sound in Washington, and Melvin Oliver was selected to lead Pitzer College in California. Additionally, in 2017, HistoryMaker Gary S. May became chancellor of the University of California, Davis campus; and, in 2018, HistoryMaker Thomas A. Parhamwas appointed president of California State University, Dominguez Hills.

As “African American firsts” continue to navigate the president’s office, the story of African American presidents of PWIs is one that is still one actively being written. Will we see a more diverse, accessible campus or curriculum, or will the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to review a pair of cases that challenge the use of race as a factor in admissions at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina impede potential progress? The jury is still out. Only time will tell.