“I have come through the doors of hell, because I am Black, because I am poor, because I live in America, and because I am determined to be both a creative artist and maintain my inner integrity and my instinctive need to be free”—Margaret Walker

After her poem “For My People” propelled Margaret Walker to fame in 1937, while she was in her early 20s, she was considered a peer by nearly every important African American writer and thinker of the mid-20th century—from Langston Hughes to John Hope Franklin.

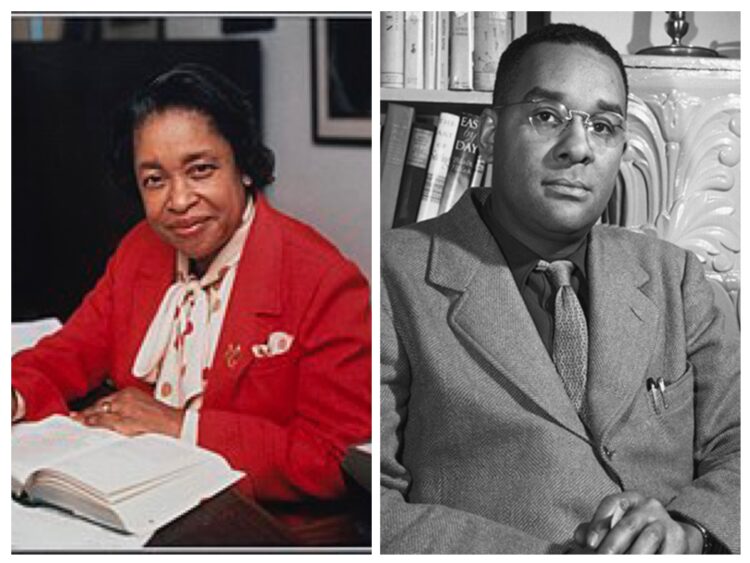

Walker was born in 1915 in Birmingham, Alabama, and her fame waned while she raised four children and toiled in academia at an historically Black college in the South. Her later-in-life, headline-grabbing literary and legal beefs with two of the leading Black male writers of her day, Richard Wright and Alex Haley, only reinforced to her the intersectional disadvantage – Black and female – that she fought against her whole life.

So why does her biographer call Margaret Walker “the most important person that nobody knows,” and what can the first major biography of Walker do to enhance her legacy?

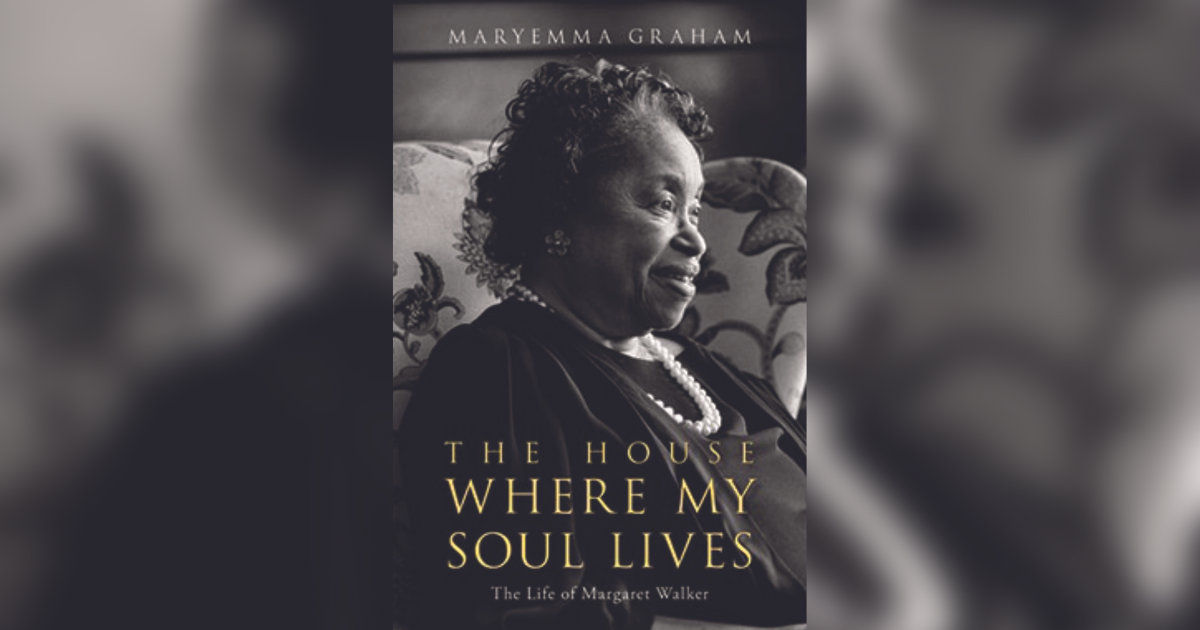

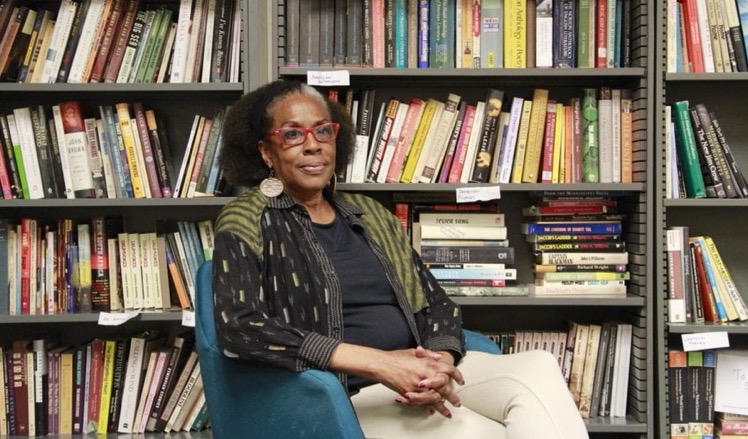

“Margaret Walker is every woman who is brilliant, who has ideas, but who is ahead of her time,” said Maryemma Graham, Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Kansas and author of the new book, “The House Where My Soul Lives: The Life of Margaret Walker.”

“She was a midwife for the Black women’s literary renaissance.” Beyond recounting her triumphs, Graham hopes the previously unpublished journal entries and photographs she has brought to light will contextualize the later-life caricature of Walker – that of “an embittered old woman who was jilted” in love by Wright and who wrote an unflattering biography of him, which added to the humiliation of losing her plagiarism suit against Haley.

The author met Walker at Northwestern University, Walker’s alma mater, when Walker was a visiting Writer In Residence. At one time in 1934, Walker and fellow students protested discrimination at Northwestern, and the president answered, saying, “their presence at the elite private institution was a privilege, not a right.”

Connecting Walker to the present day, Graham reminds readers that in one of her last widely published essays, “Whose ‘Boy’ Is This?,” Walker excoriated both Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and his former co-worker, Anita Hill, whose accusation of past sexual harassment rocked Thomas’ 1991 confirmation hearing.

Graham details Walker’s life as a preacher’s daughter in the Jim Crow South and her initial fame as a poet. Walker was living in Chicago and working for the WPA when she won the Yale University Series of Younger Poets Award in 1941 for her volume “For My People.” This signature poem encompasses the strengths and struggles of Blacks not only in Chicago but throughout America.

Its fame soon spread. “You couldn’t grow up in the segregated South and not know it,” said Graham, who recited the title poem as a young woman for church programs. “It is one of the most recited poems in the Black canon. A long poem, it stretches through the slavery and migration periods, on through urban America. It’s lyrical. It has actually been put to music. It rings in your ears so that when you hear it again, you remember the feeling you got the first time you heard it.”

Walker’s experiences in Wright’s influential Leftist writers’ group in pre-war Chicago are an important chapter of the biography. Walker and Wright fell out before his novel “Native Son” made him the man of the hour in 1940. Walker then found love with the man she would marry, Firnist James Alexander, and a professional home on the faculty of Jackson State University. And despite her responsibilities, with marriage and four children, her career reached its zenith with the novel “Jubilee” in 1966.

“It is the first book written in the authentic voice of an enslaved Black woman in the modern period,” Graham said. “Walker was the precursor to an entire genre that Toni Morrison helped to consolidate in ‘Beloved,’ which today we call the neo-slave narrative.”

Graham said “Jubliee” is “Walker’s family chronicle and her great-grandmother’s story fictionalized.”

Consequently, it hurt when Walker recognized elements of “Jubilee” in Haley’s 1976 novel “Roots: The Saga of an American Family.”

As it emerged later, “Haley did, in fact, use Walker’s book and others, and she went ballistic when she recognized it, and she later sued and lost.” Graham said Walker felt that she wanted people to know it. But she didn’t have the kind of high-priced representation that she needed.

That was only exacerbated by Walker’s biography, “Richard Wright: Daemonic Genius,” which came out in 1988 after delays caused by a dismissed lawsuit filed by Wright’s estate claiming copyright infringement for Walker’s use of their correspondence.

Graham said Walker was an inspirational figure to her when they first met in the early 1970s. By tracing the highs and lows of Walker’s life in her book, Graham hopes to unravel a complicated story that can inspire a new generation. The book is available online everywhere.

Elaine Hegwood Bowen, M.S.J., is the Entertainment Editor for the Chicago Crusader. She is a National Newspaper Publishers Association ‘Entertainment Writing’ award winner, contributor to “Rust Belt Chicago” and the author of “Old School Adventures from Englewood: South Side of Chicago.” For info, Old School Adventures from Englewood—South Side of Chicago (lulu.com) or email: [email protected].