By Stephanie Gadlin

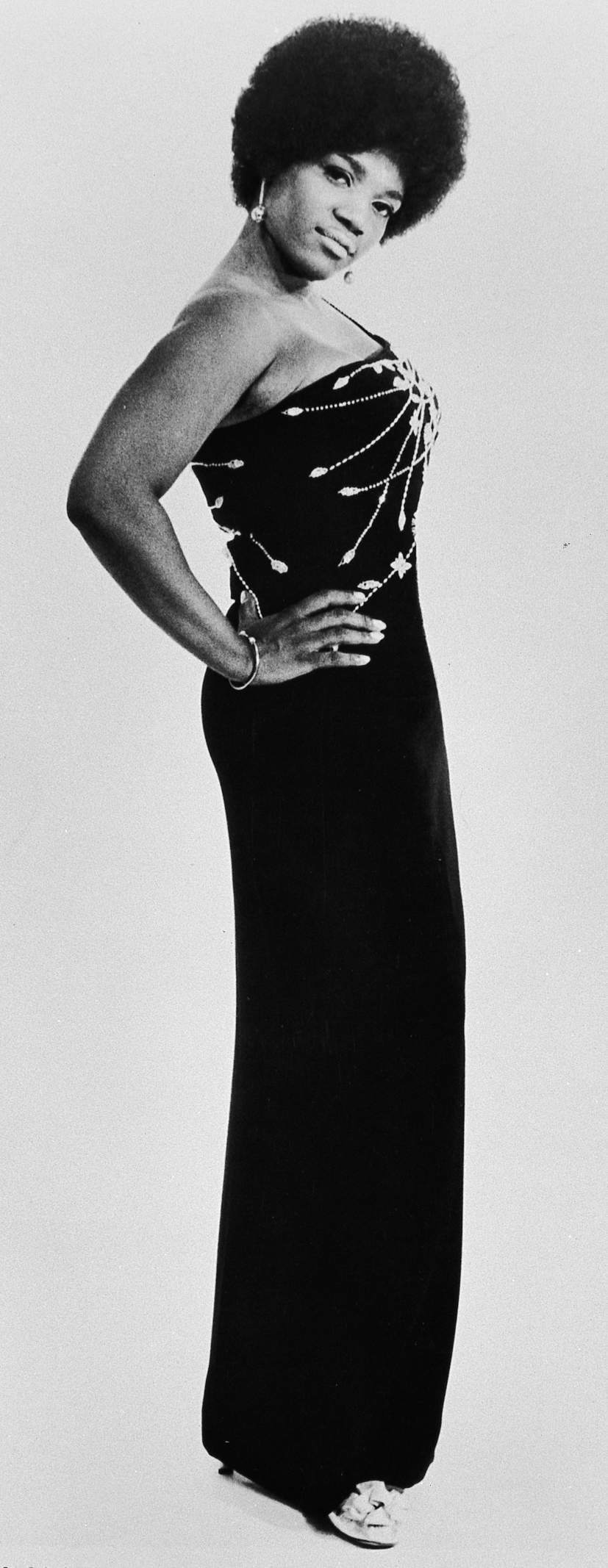

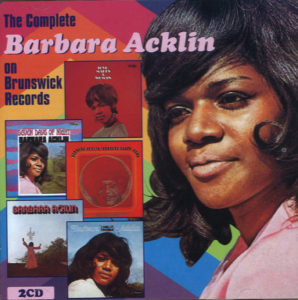

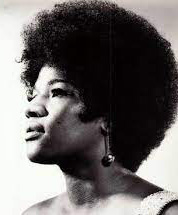

With a voice as smooth as honey mixed with hot buttered soul, Barbara Acklin became one of the most prolific singer/songwriters of the 20th Century. Regarded as the “First Lady of Brunswick,” or soul empress, Acklin sold millions of records, and is responsible for chart-topping hits such as “Have You Seen Her,” and “Stoned Out of My Mind,” by The Chi-Lites.

In recognition of Black History Month, Brunswick Records honored Acklin for her lifelong contributions to American music, issuing her estate a set of commemorative plaques highlighting her contributions.

“Am I The Same Girl” is currently Acklin’s top-ranking recording on Spotify with nearly 4.5 million streams, even more than the Swing Out Sister’s 1992 hit version of the song, streamed more than 3 million times.

“Barbara Acklin is a history maker,” said Paul Tarnopol, president and co-owner of Brunswick Record Corporation, and son of the late Nat Tarnopol, the label’s chief architect.

“This industry honor is long overdue. With this recognition, Barbara’s contributions will be forever cemented in music history. She was one of the most prolific singer-songwriters of our time, and we are pleased that Brunswick was instrumental in her success.”

Born in 1943 in Oakland, California, Acklin moved with her working-class parents to Chicago when she was about four or five years old. After the family settled in Bronzeville on the South Side, the budding soprano honed her voice in the choir at Big Zion Baptist Church before graduating from Dunbar High School in 1961.

Soon thereafter, she earned money as a waitress at the Club DeLisa and also as a member of the Bill Cody Dancers, where she became a standout talent.

Club DeLisa, 5521 S. State St., was owned by the four DeLisa brothers Jimmy, Mike, Louis and John, before eventually being bought and rebranded by deejays Pervis Spann and E. Rodney Jones in 1966.

For months and with the help of her cousin Monk Higgins who worked as a producer with St. Lawrence Records, the aspiring singer tried to jump start her career. She recorded a song under the name, “Barbara Allen,” with the label and also performed backup vocals for other emerging Chicago acts.

In 1966 she took a receptionist job at Brunswick’s office in a two-flat located at 1449 S. Michigan Ave. on Record Row (see ‘Record Row’ sidebar). There, she would go on to help craft the label’s signature sound, making it a music powerhouse for a decade.

Though originally established in 1916, by the mid-1960s Brunswick was exclusively home to African American recording artists such as Jackie Wilson, (“Lonely Teardrops”) Little Richard (“Try Some of Mine”), Gene Chandler (“The Girl Don’t Care”), Tyrone Davis (“Turn Back the Hands of Time”), The Chi-Lites (“Oh Girl”) and the Artistics (“I’m Gonna Miss You”).

Buoyed by powerful WVON deejay Al Benson, who could make or break tunes on his popular radio shows, Brunswick grew instrumental in developing a new genre of music, called “Chicago Soul,” a sound rich in full-bodied gospel, blues and jazz.

Along with Chess Records in Chicago, Detroit’s Motown Records, and Stax Records out of Memphis, Brunswick’s classic soul catalog ranges from 1957 to 1982 (having transformed from the Decca Records imprint to its own R&B label in 1960). A staple of Record Row, the imprint became an important hub for emerging local artists.

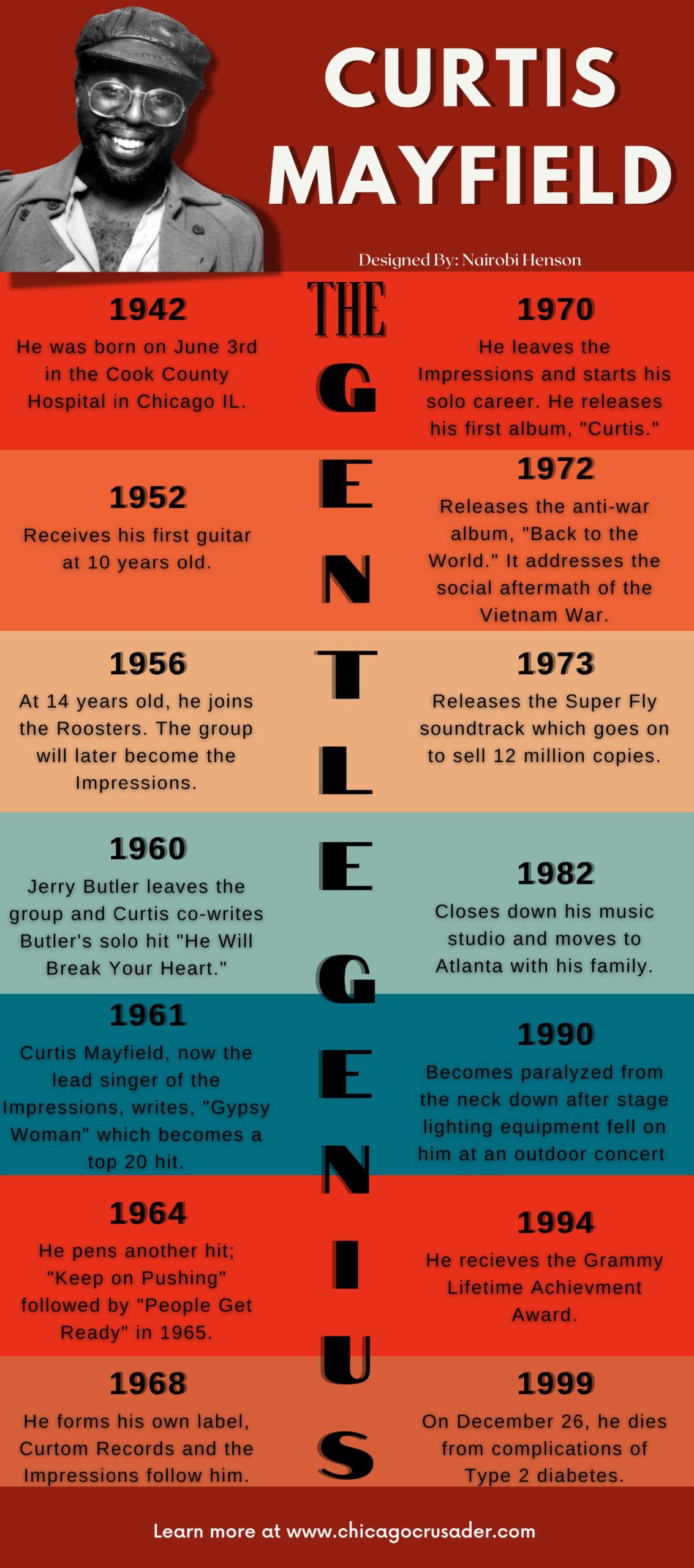

It was on this mile and a half stretch down South Michigan Avenue that a 14-year-old Curtis Mayfield blossomed into one of the world’s most gifted, prolific and productive singer-songwriters in history, with more than 1,700 songs. Starting out on Black-owned Vee Jay Records and Columbia’s OKeh imprint, the musician and Impression’s singer eventually started his own label, before turning solo in 1970.

It was while working as a producer at OKeh that Mayfield forged a bond with Carl Henry Davis, Sr., the sculptor of Chicago Soul. Few would argue that he was part of the secret sauce to the city’s meteoric rise as a leader in Black music. Though it would take years for the term “super producer” to be coined in reference to the likes of Kanye West, Pharrell Williams or Sean “P. Diddy” Combs, few would argue that Davis, a South Side native, would surely be considered its first.

Davis, who graduated from Englewood High School and enlisted in the U.S. Army, started his career in 1955 as an assistant to Benson, who at the time was working at WGES radio. The deejay was also the uncle and mentor to the Leaner siblings, one of whom owned a record label and the other who owned a record distribution company. (see “Leaner Brothers Sidebar”)

About the time Acklin was graduating from Dunbar, Davis had built a name for himself as A&R director at Colombia’s OKeh Records. By ’61 he had become a sought-after producer and arranger, not just by Black-owned labels, but also those controlled by others. After successes with Mayfield, Major Lance, Gene Chandler, Billy Butler, Walter Jackson, and a slew of other acts, Davis was recruited to Brunswick Records.

“My father had an ear for music, having had major success with Gene Chandler,” the late producer’s son, Reverend Carl H. Davis, Jr., told the Crusader. “My father went to my mom, who owned her own beauty salon at 79th and Eberhart and she gave Dad his first $500 loan to go into the studio to [produce] the ‘Duke of Earl.’”

As Davis embarked on his career, hyper-segregated Chicago was becoming the epicenter of Black entrepreneurship and success. In addition to record labels, distribution and marketing companies, African American-owned enterprises generated enough wealth to solidify the city’s Black middle class and carve out a period of progress and prosperity.

Nearly 25 percent of Chicago’s population was African American, living on the South and West sides. A bevy of Black-owned restaurants, entertainment venues like the Regal Theater, retail shops and specialty stores kept the Black Belt thriving. The success of such businesses continued to attract Southerners, who entered the Windy City with hope and determination, wanting to escape the brutal realism of Jim Crow.

The wealth and talent also drew the attention of Jews, Italians and Irish who saw Black Chicago’s concentrated wealth, political power and influence growing.

The biggest stars in music all hailed from the City of Big Shoulders. Trumpeter Louis Armstrong had found success there as a jazz musician. Jazz vocalist and pianist Nathaniel “King” Cole attended Wendell Phillips High School and grew up in Bronzeville. Before Dinah Washington started her secular music career, she was part of the Sallie Martin Singers. Thomas Dorsey had already placed Chicago on the map as the epicenter of gospel music with the powerful backing of singer Mahaila Jackson.

The biggest stars in music all hailed from the City of Big Shoulders. Trumpeter Louis Armstrong had found success there as a jazz musician. Jazz vocalist and pianist Nathaniel “King” Cole attended Wendell Phillips High School and grew up in Bronzeville. Before Dinah Washington started her secular music career, she was part of the Sallie Martin Singers. Thomas Dorsey had already placed Chicago on the map as the epicenter of gospel music with the powerful backing of singer Mahaila Jackson.

With Nat Tarnapol as Brunswick president, and as a handful of other whites ran the business side, Davis was responsible for all things creative. Initially starting out as a producer-arranger, he was promoted to A&R Director and eventually Vice President and shareholder. As such he had a hand in all of the artists’ careers signed to the company–that, in addition to scores of African American acts on independent and competing labels.

“He was basically in control at Brunswick, outside of that Tarnopol was the president,” Davis said. “(Nat Tarnopol) wasn’t a producer, but Dad was. So they brought him in, and he began to bring in all these different acts.

“So it was a young, old trio, Walter Jackson, and eventually the Chi-Lites, the Dells and Tyrone Davis,” the minister and corporate executive told the Crusader.

“(Acklin) started out as his secretary. He would have so many people seeking him out, and asking for a shot. After leaving Brunswick, he even had a hand in launching the career of Baby Face, who was back then in a group out of Indianapolis.”

“My father even worked with Cassius Clay,” Davis, Jr. also added.

“Sam Cooke had brought him to my Dad during the times when they had banned him from boxing, and he thought he would pivot to a recording career. And (the three of them) were in the Brunswick studio. And according to my father, (Muhammad Ali) couldn’t hold a note, so he told him ‘don’t quit your day job.’”

The younger Davis described his father as not only a pioneer in Black music but also a visionary, rooted in community.

The younger Davis described his father as not only a pioneer in Black music but also a visionary, rooted in community.

“We lived a few blocks over from Barbara Acklin and I was best friends with her son Marcus. I saw her all of the time. She was one of many artists who came to our house, which also drew a lot of neighborhood kids.”

Davis, like Acklin, lived in the affluent Pill Hill neighborhood, home to a multitude of African American professionals, and named such due to the high volume of physicians who owned homes in that community. It was not uncommon for musicians and songwriters to host late night jam sessions in the Davis family’s basement.

“Once Dad told me and my brother not to tell anyone that the Jackson 5 would be staying the night at our home,” he shared, laughing. “We told everyone. By the time they were done with their concert, there was no way they could come to our house. It was surrounded by teen girls. My father looked at us and yelled, ‘what did you do’?”

Before Carl Davis died in 2012, the devoted father of eight noted in a memoir, “My thanks to Otis Leavill because he was the one who had brought Barbara into the company. When we built our office at Roosevelt and Wabash, Barbara’s desk was stationed in the reception area, and my office was behind that,” he said in the book, “The Man Behind the Music: The Legendary Carl Davis.”

It was while sitting behind Brunswick’s reception desk that Acklin met national heartthrob and crooner Jackie Wilson and quickly pitched a song she had written. “Whispers Getting Louder” became a hit for Wilson and the song propelled his career back to the top of the charts. The song advanced to Number 5 on the Billboard R&B chart.

“Here was this big star coming through and Barbara wanted him to hear a song she’d just written. (He) asked her to sing the song for him and it instantly blew him away,” said Marshall Thompson, the last surviving original member of The Chi-Lites. “That’s when Jackie told Carl Davis that she could not only write songs but she could sing them too. Barbara became a triple-threat — writer, arranger and singer –and she could really belt it out.”

Davis, Sr. recalled of the time, “After a while, Jackie started annoying me about producing Barbara. He would always say, “Why don’t you do something with Barbara? The girl can sing.” I said, “Barbara? Man, Barbara’s my secretary. She’s my receptionist,” Davis wrote. “He said, “Yeah, but she can sing, too.” The truth was, I heard Barbara sing before and I knew she could sing. But I was hesitant because I wasn’t really good with women singers, except for the Opals, so I basically didn’t want to be bothered with producing her.”

It is an understatement that later Davis felt lucky at giving Acklin the break she had been seeking since high school. “Jackie was relentless, and eventually he started saying, “If you don’t want to do it, then let me produce her for Brunswick.”

Shortly after her solo success, Acklin began dating a member of the Chi-Lites, Eugene Record.

The Chi-Lites formed at Hyde Park High School in 1957 with Thompson, Creadel Jones, Robert “Squirrel” Lester, Burt Bowen, Clarence Johnson, and Eugene Record, who went to rival Englewood High School. The supergroup would go on to record scores of chart-topping hits, some of which were co-written by Acklin, with many being certified gold after selling one million records.

In 2021, the group received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The Chi-Lites were inducted into the Vocal Group Hall of Fame and the R&B Music Hall of Fame in 2013.

Acklin’s songwriting career went to new heights when she partnered with Record, who doubled as the The Chi-Lites’ lead singer with falsetto clarity. Together the duo penned the haunting “Have You Seen Her”, and many of the quartet’s chart-topping hits over the years, and “Two Little Kids,” by Peaches & Herb, which became a Top 20 hit in 1968.

She also authored and co-wrote a number of hit songs for other Brunswick artists, often teaming up with producers Davis, Otis Leavill, Richard Parker, Willie Henderson, and Leo Graham. The songstress worked with then up-and-coming engineering legend Bruce Swedien, who later was credited with developing Michael Jackson’s signature chart-busting sound.

Incidentally, “Two Little Kids” was nominated for a Grammy award but lost to Aretha Franklin’s “Chain of Fools.” Her track, “Am I the Same Girl,” was re-mixed without her vocals and released as an instrumental and named as “Soulful Strut,” by jazz duo Young-Holt Unlimited and also became a hit after frequent play on WVON.

“Barbara was a beautiful woman in a room full of guys–but she was tough, didn’t take no stuff, and could hold her own with any of us,” Thompson told the Crusader. “When we were on the road she kept us together. She watched our back and we watched hers; we were like a family.”

It was bad enough that we all had to deal with a lot of racial hostility, especially touring the South, but (Barbara) also had to deal with folks who didn’t always treat women with the respect they deserved.”

It was bad enough that we all had to deal with a lot of racial hostility, especially touring the South, but (Barbara) also had to deal with folks who didn’t always treat women with the respect they deserved.”

Early in her career, Acklin modeled her singing style after her icon Dionne Warwick, but later developed her own unique phrasing and raw, sultry sound.

Her deeply personal lyrics often told the story of unrequited love; enduring hope; passion and pain; and the fear of loss.

As Acklin’s career as a singer-songwriter flourished, Brunswick helped her shatter glass ceilings by providing her with the opportunity to work as a recording engineer, arranger and backup singer for several of the label’s artists.

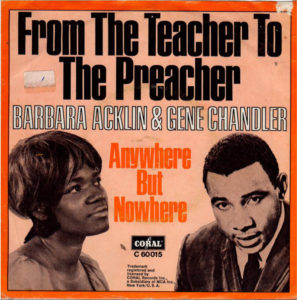

In 1968 she recorded a duet, “From the Teacher to the Preacher,” with Chandler and hit the road with him. While touring the South with Brunswick artists, her album, “Love Makes A Woman,” catapulted Acklin into the stratosphere with the release of its title track reaching number three on the R&B chart and number 15 on the U.S. pop chart, earning her a gold record.

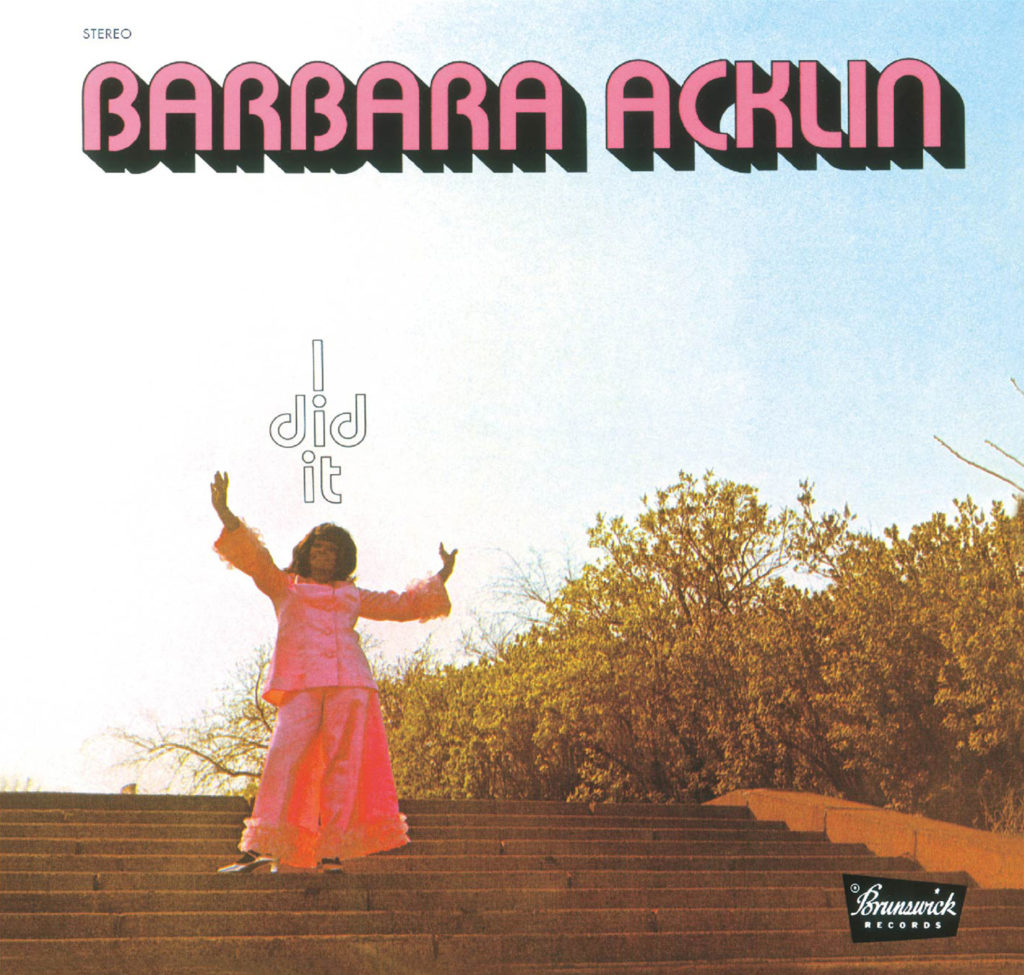

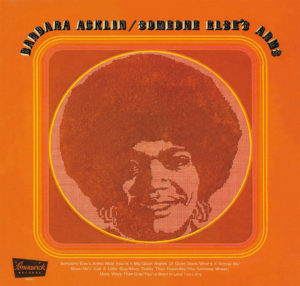

She subsequently recorded four more Brunswick albums, Seven Days of Night (1969), Someone Else’s Arms (1970), I Did It (1971), and I Call It Trouble (1973).

Born Eugene D. Dixon in 1937, Chandler went to Englewood High School where he met fellow student Carl Davis, and joined a burgeoning doo-wop group. After a partnership with young singer-songwriter and composer Curtis Mayfield, he reached success with songs such as “Duke of Earl (1962),” and “Rainbow (1963)” on the Vee Jay label. In 1967, he signed with Brunswick, though he also had a unique deal to release records under the Chess label.

At Brunswick, Chandler worked primarily with songwriter Ken Lewis, and together they hammered out a number of hits. The Crusaderattempted to contact Mr. Chandler who initially agreed to speak about Acklin. He reportedly spends his time between his homes in a Chicago suburb and Florida.

“It was Gene’s idea,” Barbara Acklin noted of their collaborations in Chicago Soul, by Robert Pruter. “He heard me singing and thought that I had a pretty good voice. …‘From the Teacher to the Preacher’ did really well. So Gene took me on the road with him and gave me five hundred dollars a night to sing one song.”

Chandler would go on to be twice inducted into the Rhythm and Blues Hall of Fame in 2014 and again in 2016 for his contributions to American music. Acklin, however, remained in the margins of music history, while her male counterparts received accolade after accolade.

Chandler would go on to be twice inducted into the Rhythm and Blues Hall of Fame in 2014 and again in 2016 for his contributions to American music. Acklin, however, remained in the margins of music history, while her male counterparts received accolade after accolade.

“Love Makes A Woman,” supposedly written by a trio of men, reached number three on the R&B charts and remained in place for nearly four months.

“Barbara was a beautiful, soulful lady,” said legendary arranger Willie Henderson, in a rare interview. He worked with Acklin for the better part of three decades.

“She was a tremendous talent, a hard worker, and an all-around nice person. Barbara used to walk around the office, throwing out a few lyrics and we’d all go back and forth until we developed it into something. She was always writing, always creating.”

Henderson also noted, “The times were changing, we were young and doing our best to contribute in some kind of way,” he said. “Martin Luther King, Jr., had moved to Chicago at one point; and his murder had a profound impact on how we all thought about the transformative power of music. Barbara played a big part in shaping the Chicago sound; and Brunswick gave us the space to be creative and contribute in a meaningful way.”

After leaving the label, Acklin signed with Capitol Records in 1974, and she continued to perform and nurture younger artists entering the business. Married three times, the songstress raised two children, a godson, and two stepdaughters in the affluent Pill Hill neighborhood. Her home on South Ridgeland Avenue was a revolving door of musicians, celebrities, political figures, and other notables, many of whom attended late-night jam sessions there.

“My mother blazed trails for Black people and especially women in the recording industry,” said Samotta Acklin, herself a singer and producer who travels the world performing covers of her mother’s songs. “She broke these barriers while juggling a marriage, raising two children, and being a godmother to neighborhood kids.”

“The Acklin family is honored to accept this recognition from Brunswick,” she continued. “My mother’s story is long overdue and is finally being told. I’m also grateful to the global DJ community that continues to stream my mother’s music and introduce her to a new generation of music lovers.”

“The Acklin family is honored to accept this recognition from Brunswick,” she continued. “My mother’s story is long overdue and is finally being told. I’m also grateful to the global DJ community that continues to stream my mother’s music and introduce her to a new generation of music lovers.”

In 1982 the Jam recorded “Stoned Out of My Mind” and in 1990 MC Hammer released a hip hop version of “Have You Seen Her” propelling it to a Top Ten hit for the rapper. In 1992 “Am I the Same Girl” was a Top Thirty UK hit for Swing Out Sister–the song had also been covered in 1969 by white pop singer Dusty Springfield in the United Kingdom. Though she [Acklin] continued to record, her new music was rarely met with the same enthusiasm as other releases.

She loaned her buttery, smooth backing vocals to an album, “The Gospel Truth (1993)” released by Otis Clay, a blues and soul singer. Acklin also toured as backup singer for Tyrone Davis and as a manager for Holly Maxwell, Ike Turner’s replacement for his estranged wife Tina.

In 1970, she released “I Did It,” making the Billboard charts, holding at number 28 for two months. After two more releases, “I’ll Bake Me A Man,” and “Lady, Lady, Lady,” Acklin parted ways with Brunswick in 1973.

By this time, Chicago’s Black-owned record labels and its similarly owned business infrastructure had become fractured. In addition, the business of music had evolved once again, and with it so had Black Music. Brunswick continued with modest success producing additional hits for Tyrone Davis and The Chi-Lites, before the Stylistics, through the “Philadelphia Sound,” began to take the crown.

Acklin, entering her 40s, continued working and providing backup vocals for various groups, but due to the shift failed to reach her previous success. In 1975 Carl Davis, was indicted along with Tarnapol and other Brunswick executives by the federal government in what became known as the “payola scandal.”

Acklin, entering her 40s, continued working and providing backup vocals for various groups, but due to the shift failed to reach her previous success. In 1975 Carl Davis, was indicted along with Tarnapol and other Brunswick executives by the federal government in what became known as the “payola scandal.”

According to an appeal filed in the case, the feds charged Brunswick officials with “funny” accounting.

Reportedly, “sales of over $350,000 worth of Brunswick records were not recorded on the corporation’s books, (and) that the proceeds of the sales in the form of cash or merchandise were retained by the defendants or used to create a fund out of which improper payments were made to disc jockeys and program directors of radio stations to secure favored treatment of Brunswick and Dakar recordings.

“…The transactions were used to defraud the United States by impeding the functions of the Internal Revenue Service, and to defraud artists, songwriters and publishers to whom the corporations were obligated to pay royalties based on sales as well as radio stations and the listening public who were deprived of the honest services of the radio stations’ employees,” court documents show.

Though Davis was acquitted in the trial a year later, the stain of the trial haunts his legacy like an unrelenting ghost. “He was accused of being a part of payola and at one point it was taken to the Supreme Court,” his son said.

“It was determined that my father was not involved at all and he was vindicated.

“It was determined that my father was not involved at all and he was vindicated.

“What they didn’t understand was that even though my father was the face of Brunswick he didn’t own it nor was he the CEO,” he said. “(He was the face of the label) and because that’s the only one they had access to, then it must be ‘certainly, if Brunswick is stealing money from us, then it must be that Carl Davis is stealing money from us.’

“I understand that mindset, but it was very inaccurate,” Davis, Jr., told the Crusader.

“I’ve had many people, including (former Atlanta Mayor) Keisha Lance Bottoms, an attorney by the way, track down her father’s royalties. She’s on record, saying that she was told the same thing. But when she looked up (who was responsible for father’s unpaid royalties), she found it had nothing to do with my father at all.

“My Dad was the face of Brunswick, especially to the Black community, and to Chicago, but he was not the one writing the checks. Nor was he the one in control of all the money,” he said. “At the end of his career he got none of the things that were promised to him.”

As the music industry shifted to newer and younger acts, and with the emergence of rap and its specialty of “sampling,” the songstress’ music began to find new fans overseas. Sampling is a production technique that includes an element of a pre-existing recording by another artist and weaves it in a new composition.

“The club deejays were remixing my mother’s records and it caused a resurgence of interest in her in Europe,” Samotta Acklin said. “She was getting requests to tour abroad. People were asking if she had new music.”

Acklin was on the verge of reviving her career and unveiling new music when she became ill in Nebraska and died unexpectedly on November 27, 1998.

In 2017, the songstress was posthumously inducted into the Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

“So (before the pandemic) I was in Spain,” Acklin told the Crusader, “They brought me over there and I sang about seven songs of my mother’s love me for a woman to me, the same girl. It was so much fun.”

With today’s resurgence in music, art and cultural aesthetic from that era, Brunswick Records may be seeing a resurgence in its historic archive of Chicago soul music. Much of its catalog is available on streaming services and is available to a new generation of music connoisseurs, producers and arrangers.

Post pandemic, Samotta Acklin is in the studio working on a new rendition of “Love Makes A Woman,” and other tunes that showcase the diversity and depth of her mother’s songwriting and song stylings.

Post pandemic, Samotta Acklin is in the studio working on a new rendition of “Love Makes A Woman,” and other tunes that showcase the diversity and depth of her mother’s songwriting and song stylings.

On March 7, she will host a concert performance, “It’s All About Love,” at 7 p.m. at the Promontory, 5311 S. Lake Park, in the Hyde Park community.

Barbara Acklin’s legacy and impact on music lives on through her daughter’s homage.

Face masks and proof of vaccinations are required for entry.

Links to Black History Special Edition 2022 Stories & Timeline:

Dynamic Duo: The Leaner Brothers

The Chicago Sound: The Legacy of Record Row

Timeline: A Brief History of Chicago Soul–Hit Records and Black Owned Record Labels