The visitors keep coming. Elevators are still packed. Museum exhibits continue to glow with intrigue, power and enlightenment.

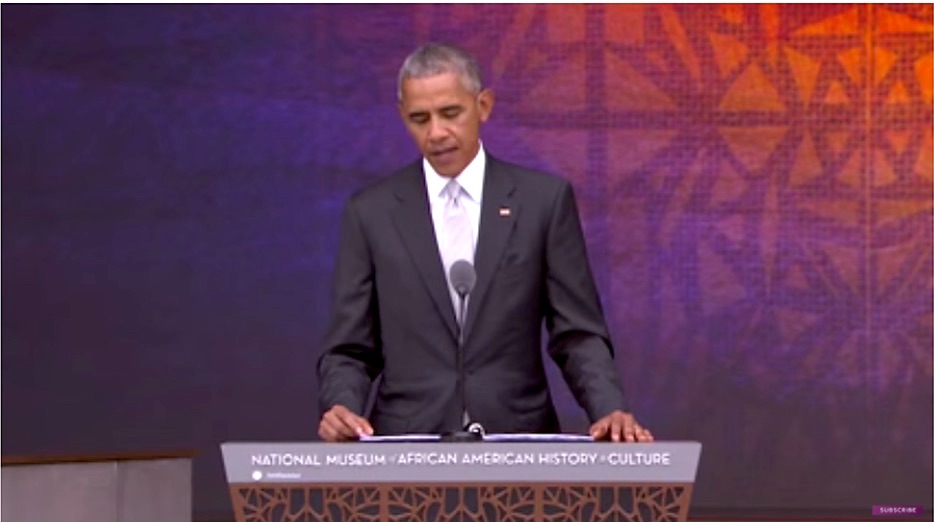

Five years ago, interest in Black history peaked as Barack Obama, the nation’s first Black president, opened the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. After stunning reviews in major newspapers, excitement over the museum’s opening reached levels not seen in recent memory.

For Blacks across America, it was a proud and defining moment that capped a 100-year struggle to open a national museum that would fully tell the story, contributions and achievements of a people whose history had been ignored for so long.

On a cloudy day, the nation watched on live television as three U.S. presidents, Black political dignitaries and celebrities heralded a museum opening long overdue.

In Chicago, crowds packed the auditorium at the DuSable Museum of African American History to watch the opening ceremony live. The ceremony had more ties to Chicago than perhaps any other city in America.

The Obamas from Hyde Park led the ceremony that included former Ebony and Jet publisher Linda Johnson Rice, former Chicago History Museum and now NMAAHC’s Lonnie Bunch, and Oprah Winfrey, a former Chicago resident who found stardom in the Windy City with her namesake talk show.

When it finally opened after a grand dedication on September 14, 2016, the “Black Museum,” as many now call it, instantly became the hottest ticket in town and invigorated the cultural scene in the nation’s capital and gave visitors a refreshing alternative to traditional attractions on the National Mall.

Like most national museums, the ticket was free, but that made it even hotter, so much so that visitors had to obtain timed passes to get in.

Visitors without timed passes waited hours, even days to get into the museum. Once inside, they would see thousands of photos, artifacts and exhibits that take attendees on a moving but empowering journey of Black history and culture over five floors in the 350,000-square-foot building.

I, along with over 1,200 journalists and publishers of Black newspapers, toured the museum during a media day held a week before the museum opened to the public in 2016. It was an experience I’ll never forget.

For eight hours, I roamed the place, gazing at an old wooden piano Father Thomas Dorsey used while at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Bronzeville. I got chills when I saw a red Kleagle Ku Klux Klan robe, which is worn by an officer who recruits members. For several minutes I gazed at a real, but decommissioned, PT-13D World War II plane flown by Tuskegee Airmen. The museum is where I first learned about Oak Bluffs, the historic affluent Black community on Martha’s Vineyard that many called “The Black Hamptons.” Intrigued, I later wrote a story about it.

One exhibit that I never got to see was a special section of the museum that housed the casket of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Chicago youth who was murdered by two white men in 1955. Today, five years after the museum’s historic grand opening to the world, Till’s casket remains the most popular exhibit, with four-hour long waits. Last month, the NMAAHC displayed the bullet-ridden historical marker that was placed by the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi where Till’s body was found.

The exhibit has cemented the museum and the city as the top destination for many Blacks. Black churches arrive by the busloads on field trips. Black families continue to host family reunions here. The museum’s super popular Sweet Home Café has morphed into a successful catering business that serves sumptuous soul food dishes to thousands of families during the holidays.

The café along with the museum had been closed for nearly a year because of the coronavirus pandemic, now the NMAAHC is regaining its momentum as it marks the 5th Anniversary of its opening.

The museum is hosting an array of interactive and virtual programming initiatives, and a new exhibition in its Robert F. Smith Family History Center.

The September lineup opens with a discussion of the newly released documentary My Name Is Pauli Murray, which focuses on the pioneering attorney, activist, priest and dedicated memoirist Pauli Murray, who died in 1985 after a distinguished career.

But the biggest draw remains the museum itself. The prominent and popular website, Trip Advisor, once rated the NMAAHC the second most popular attraction on its list of Best Things to Do. The National Museum of Natural History was the first and the Lincoln Memorial is fourth. The NMAAHC is also on the tourist lists of Conde Nast Traveler and U.S. News and World Report.

Nearly 3,000 out of 3,500 tourists gave the NMAAHC five stars on Trip Advisor.

One reviewer who visited the museum in August said, “This is hands down the best museum I’ve seen. Exhibits are vast and impressive. The structure itself is a piece of art. Exquisitely done!”

After visiting the museum earlier this month, Kelly D. from Tampa, Florida, said, “This is a fantastic museum, I’d say one of the best I’ve ever been to. The museum is well laid out and well run.

“The lower levels cover the history, while the upper levels cover cultural impacts. There is a great mix of art, artifacts, and audio. I spent four hours and could have spent at least another hour reading everything. Don’t miss this museum.”

One reviewer from Colorado Springs, Colorado, said, “Amazing, wonderful museum! Spend one day below ground and the other on the upper levels. Four hours at least for each visit. Very well done in all respects!”

Many reviewers who visited the museum after it reopened in June said it was still a challenge in getting timed passes to get inside. They advise others to plan early and expect to spend at least four hours there.

When it opened in 2016, the NMAAHC became the world’s largest museum dedicated to Black history and culture with nearly 40,000 objects in its collection and about 3,500 items are on display.

Three million people visited the museum in its first full year, exceeding expectations. More than 600,000 people visited the museum in its first three months. After six months, 1.2 million people had visited the NMAAHC, making it one of the four most-visited Smithsonian museums. Many patrons spent an average of six hours at the museum; twice longer than was estimated before the museum’s opening.

By the end of 2018, the museum had received just under five million visitors since it opened, 1.9 million of whom visited in 2018.

In its short history, the NMAAHC has not been immune to controversy. When the museum first opened, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas was largely mentioned only in connection with the contentious 1991 confirmation battle that involved allegations of sexual harassment by Anita Hill, a former Thomas staffer. In 2019, Thomas was upset at an exhibit that he said was created without the museum contacting him first.

The exhibit focuses on Thomas’ conservative views about affirmative action, which, according to his memoir, was shaped by his experiences at Yale Law School. There, Thomas said he felt that whites resented him and assumed he was admitted because of racial quotas.

Thomas said that racial preference had robbed his achievement of its true value.

On the fourth floor of the museum in the Culture Gallery, is a photo of the young Bill Cosby. When rape allegations surfaced in 2016, the museum added a description beneath the photo that acknowledges Cosby’s talents but mentions the revelations of alleged sexual misconduct.

(This summer, Cosby was released after serving three years in jail when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court threw out his 2018 sexual assault conviction. The court said Cosby should not have been charged in the first place after prosecutors promised not to charge him during privileged conversations).

Controversy aside, the NMAAHC remains an important symbol of hope and achievement to many Blacks.

It took nearly 100 years to get off the ground. President Herbert Hoover agreed to support the national memorial building for Blacks, but Congress failed to back it. For the next several decades, Congress would turn down legislation supporting the creation of the museum, saying it would be too costly.

Smithsonian Secretary Robert McCormick Adams, Jr., sparked controversy when he publicly suggested in 1989 that “just a wing” of the National Museum of American History should be devoted to Black culture. In 1995, The Smithsonian’s new Secretary, Ira Michael Heyman, publicly questioned the need for “ethnic” museums on the National Mall. Advocacy groups felt the Capitol Hill site at 1400 Constitution Avenue NW was too prominent and made the National Mall look crowded.

The late Congressman John Lewis is credited with the success of getting the museum built. Two of his bills in the U.S. House of Representatives failed before he filed a third one in 2001 during President George W. Bush’s term. It finally passed in the House and the Senate.

In 2003, President Bush signed it into law, creating the “National Museum of African American History and Culture Act,” which appropriated $17 million for the facility.

Media mogul Oprah Winfrey and basketball legend Michael Jordan were among numerous wealthy celebrities whose donations to the museum totaled $386 million.

The museum would be headed by Lonnie Bunch, who previously served as president and director of the Chicago History Museum from 2000 to 2005. In 2019, Bunch was promoted to serve as the 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, becoming the first Black in that role. Today, poet Kevin Young is the director of NMAAHC.

Thanks to the generosity of funding provided by The Field Foundation of Illinois, Inc. in producing this article.